Photography by Phil Sayer

When a group of Dutch designers calling themselves Droog Design rented a shop in the centre of Milan to exhibit their work during the 1993 Milan Furniture Fair, a public accustomed to slick design products immediately realized that the 1980s were gone forever. After the creative explosion of that period, design was shaken by an overwhelming return to reality. Inevitably, the Droog phenomenon was interpreted as a clear sign of the times, but Dutch design has moved on since then, and many of the individual designers who were part of Droog have gone their own way.

Hella Jongerius was one of them. ‘I was in school in the 1980s, and I didn’t like all that stuff’, she says. ‘There was a real design overkill, so for me it was a reaction to all that industrial sleekness: just give it a new jacket and you have a new product. I’m somebody who is down to earth. I’m very basic, which is why I don’t like the design world. I don’t see any reason to make new forms’. Working for Droog was a sort of watershed for Jongerius but her own work had another dimension. ‘I studied fabrics for a long time in Eindhoven, and I wanted to do something different. I came across a factory where they made moulds for bronze industrial castings using a kind of rubber. I thought it was a great material – it looked like glass and was very tactile. I thought it was a pity to use it for moulds. That’s why I took it out of its industrial context. I worked with the material by hand to make shapes out of it. Later I went to a ceramics centre where you can learn all the proper techniques, and there were people to help you in the studio. That’s when I made the porcelain service and the pots with the shards from the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum. I went on with the material, and eventually Droog spotted my work’.

Jongerius rejects the concept of perfection that is implicit in mass-production. In her vases, she reconstructs an archetypal form, combining a fragmented trace (a shard from a medieval vase given to her by a local museum) with a variety of materials and freely using car body paints to embrace the ‘rediscovered’ form in everyday life. ‘Traditional forms have a story, and you have to respect that story while also giving them a contemporary sense. I always like very much when a product shows a sign of the time or something from the street. That you know it’s made in 2000 rather than years ago’.

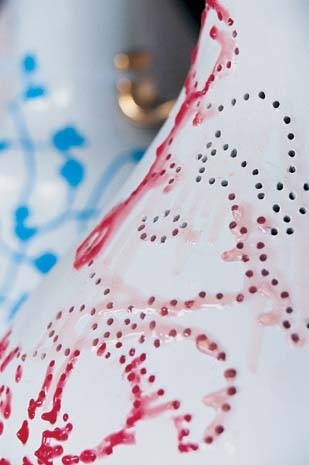

While working on the porcelain service, Jongerius noticed that if the temperature in the kiln was altered, the individual pieces (moulded and thus identical) depart from the original form and acquire slight imperfections. Having found that this imperceptible deviation from the rule, which makes every piece unique, could satisfy her personal concept of beauty, Jongerius conceived of the idea of working to fuse different worlds as in the case of ceramic and embroidery. She searched for quick solutions (using adhesive tape to join glass and ceramics, for example) in a way that expressed a contemporary vision. ‘I think if you have something very new, like what I do with rubber and tape, that you need to give people a sense of comfort in the form. A lot of people buy antiques or secondhand things because they want to buy a story, not just a product. And the story behind a product or antique is that of the makers or the material’.

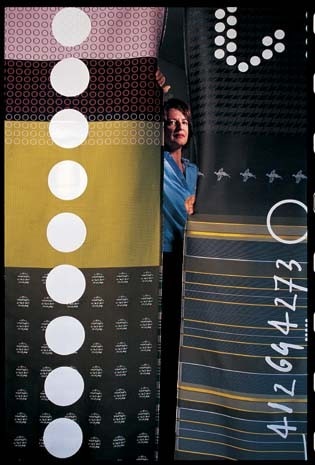

Since then Jongerius has continued to work against the ‘sleekness’ of the mass-produced object, introducing a certain element of random chance into the established order of industrial process. Creating one-off pieces industrially was an objective that she could only achieve by manipulating consolidated production methods. This is why her work requires the active participation of the firms with which she works. When Maharam asked her to develop a new decorative concept for the upholstery fabrics that the American company has manufactured for a century (it was founded by the pioneering Louis Maharam in 1902), Jongerius developed a process that would enable her to pursue industrial production of unique pieces, already tried and tested with the porcelain service. It was a case of expressing a contemporary vision for domestic decor. The new design would inevitably bring comparison with masters of the calibre of Anni Albers, Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard and Verner Panton, who had, each in his or her own way, traced a vision of the modern ornament for Maharam that remains exemplary.

After visiting the factory and its archives, Jongerius was convinced that there was no need to develop a new design. She ‘merely’ chose a number of decorative themes (dots, stripes, birds, plant motifs, houndstooth check) and combined them, allowing them to interfere with one another. In their different declensions, measured by the variation of colour and size, the decorative elements overlap and entwine in a continual flow that extends for a length of approximately three metres (equal to the decorative module). The border codes, production notes and punched holes for the jacquard weave become part of this decorative programme, which creates a casual order in the relationship between the fabric and furniture pieces. The size of the repetition is such that the sense of uniformity and continuity is lost.

Thus a set of chairs is unlikely to have the same decoration, although the chairs will maintain a strong affinity with one another. ‘From the point of view of production, it’s not a big deal to make a repetitive pattern on the scale of three metres. But they don’t usually do it, because it complicates the lives of the sales force. What interests me is that once the process is underway, it goes with the flow. I prefer to just take advantage of what is there. You have to fire porcelain at a very high temperature, and everything came out a bit out of shape. That’s what I think is the beauty. I really like the industrial process, but only if I can introduce a sense of craft to it. I’m not usually a fan of the one-off, but I do them because I need to experiment for the real thing – the industrially made objects. I work on the one-off for myself, to figure out what story I want to tell or to make things that are too far out for a company. But I like to look at the one-off in an industrial way’. Jongerius adopted a similar approach when Hermès asked her to make an installation using the patterns of its scarves: ‘I really wanted a more quiet pattern – to make the decoration more sober, use only lines, get away from colour’. Choosing designs from Hermès’ vast catalogue, she isolated the patterns from their original context and created a new one: a series of lamps in which the porcelain is combined with silk, almost creating a flow of one into the other, worlds and materials that have many affinities.

‘For me it is that you create a lot of layers in your work. Some people fall in love with decoration, while others fall in love with the material. Products don’t just have one dimension; there are more stories to tell’.