In recent years, ceramics has resurfaced almost everywhere: in courses attended by those eager to learn how to model clay, in the work of artists who use it as an expressive language, and among designers who rediscover it as a living, imperfect material — one that captures the trace of time and gesture.

After years dominated by images and screens, the act of kneading earth and water into tangible forms has returned as a response to a primal need, as old as humanity itself.

And in fact, we haven’t invented anything new.

Ceramics is one of the oldest inventions in human history — created first and foremost to solve practical needs: to contain, to preserve, to cook.

The earliest fragments date back to the Paleolithic, although it was only in the Neolithic, with the advent of agriculture and settled life, that fired clay became indispensable. From that moment on — from the Mediterranean to Mesopotamia, from China to pre-Columbian America — ceramics has accompanied the history of human habitation.

From the very beginning, people did not limit themselves to shaping functional tools; they also felt the urge to decorate them, engraving signs, motifs or figures onto the surfaces of the objects they used every day.

In this way, ceramics became both utensil and symbol — a material capable of serving and, at the same time, representing the world.

From need to language

It offers a reading of the material’s history that reveals ceramics as something profoundly anthropological — a substance tied to survival that, over time, has been transformed into language.

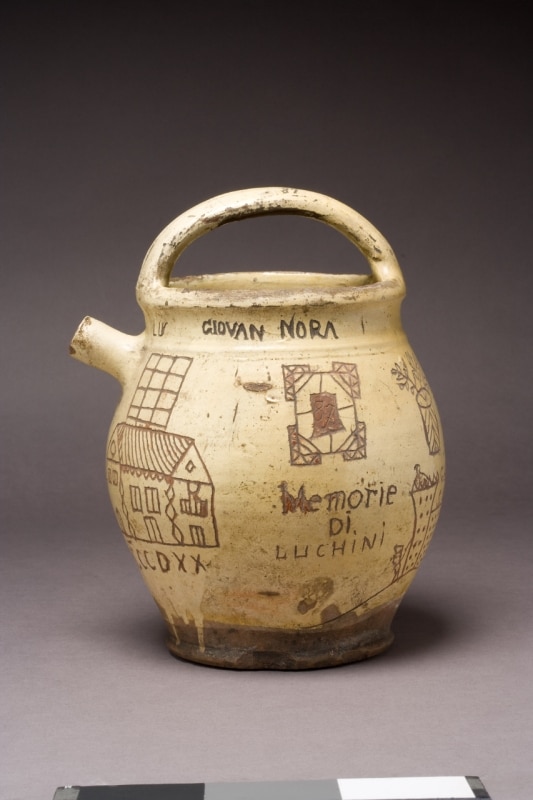

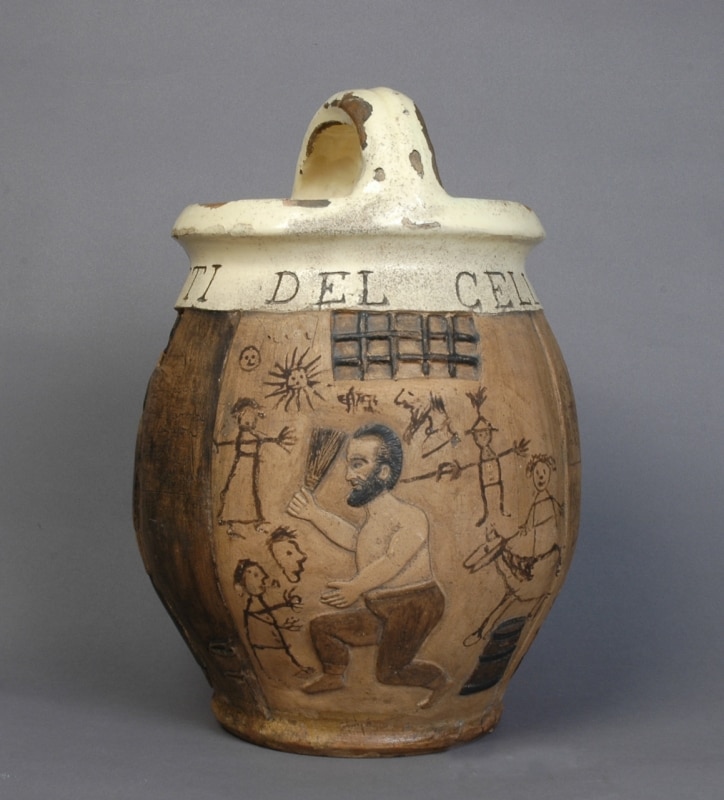

This relationship between utility and meaning, between matter and thought, emerges vividly at the Museum of Criminal Anthropology “Cesare Lombroso” in Turin. Among skull casts and measuring instruments, the museum preserves a remarkable collection of eighty terracotta jars and pitchers engraved by inmates of “Le Nuove” prison between 1870 and 1916.

Ceramics became both utensil and symbol — a material capable of serving and, at the same time, representing the world.

The museum takes its name from Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), a physician and criminologist from Verona regarded as the father of criminal anthropology. A key figure of nineteenth-century positivism, Lombroso believed that criminal behaviour had biological roots and could be identified through physical and anatomical traits.

He carried out much of his research in Turin’s prisons, collecting objects, casts and artefacts he considered representative of the “criminal mind” — pausing in particular on the sign and handwriting as potential traces of deviant impulse.

The jars of Turin

They were everyday objects, meant to hold water or food, yet for those who engraved them they also became a means of expression. Prisoners used whatever was available: the glazed clay of the jars and improvised tools — often pieces of metal or nails — to carve words and images into their surfaces.

The practice became so common that it was explicitly mentioned in the prison regulations, which strictly prohibited it.

Many of the engravings appear fragmentary, abbreviated or abruptly interrupted — partly because of the haste and secrecy of the act, and partly due to the inmates’ limited education. Most were labourers, manual workers or petty criminals from Turin’s working-class neighbourhoods, expressing themselves in a slangy Piedmontese laced with Frenchisms and neologisms.

Among the best-known creators of these engravings is Defendente Buzzo, leader of the “Bersagliè d’Vanchija” gang, composed of twenty-one members tried in 1900 for a long series of thefts. Sentenced to twenty years in prison, Buzzo left behind a remarkably coherent body of work: a jar, a plate, three bowls, a chamber pot and a medallion — all decorated in bas-relief and painted in tempera.

As Luca Spanu notes in his essay on the collection, Buzzo’s works reveal a striking iconographic awareness. Alongside allegorical figures of Liberty, Reason and Tyranny, he repeatedly portrays himself, accompanying the images with inscriptions calling for justice or revolution. One bowl reads “Rise, O People – Revolution,” while on a jar he depicts himself lying on his bunk, reading geometry books “to conquer boredom,” beside the image of a man hanging from the cell bars.

It is striking to consider how what Lombroso viewed as clear evidence of deviance — according to his theory, criminals were born as such, genetically predisposed to crime, and destined to manifest it even in prison — appears completely different today.

As Spanu points out, these objects now stand as testimonies of awareness and language: handcrafted forms of dissent and self-representation, created within a space of isolation, with an aesthetic that feels surprisingly contemporary.

From art brut to contemporary ceramics

In the years when Lombroso was collecting these objects, the idea that artistic expression could exist outside the official circuits of art had not yet taken shape.

It was only decades later, in 1945, that Jean Dubuffet coined the term art brut to describe the creations of self-taught individuals, psychiatric patients or prisoners who produced art without formal training or aesthetic ambition. Dubuffet sought a “raw” art — free from cultural conventions, capable of revealing a direct and vital impulse.

The Turin jars unconsciously anticipate that same expressive urgency: spontaneous engravings, devoid of decorative intent, born out of necessity rather than the desire to communicate with an audience.

What Lombroso viewed as clear evidence of deviance appears completely different today: testimonies of awareness and language, handcrafted forms of dissent and self-representation.

That urgency persists today in the work of many contemporary artists who, in their use of ceramics, reclaim the instinctive and tactile dimension of making.

Grayson Perry uses the vase as a narrative surface, engraving words and figures that speak of identity, guilt and desire. Sterling Ruby, on the other hand, focuses on materiality itself, allowing scratches and drips to remain visible as traces of the gesture — a form of expression that is both direct and physical.