Born in Belgium in 1928, Agnès Varda made Paris the city of her life. Her connection to it was more than geographic—it was visceral, everyday, embodied. From the very beginning, the city shaped and nourished her gaze on the world, playing an active role in the formation of the imagination of someone who would become one of the most important filmmakers of the 20th century—and beyond.

“Le Paris d’Agnès Varda, de-ci, de-là”, the exhibition currently on view at the Musée Carnavalet, does more than celebrate a key figure of auteur cinema. It invites visitors to walk in her footsteps and inhabit the city as she did: with attention, affection, and radical freedom.

This relationship takes root in the now-legendary courtyard-studio on rue Daguerre, in the 14th arrondissement, where she lived and worked continuously from 1951 to 2019: a creative epicenter where her ideas were born, and a domestic cradle where they came to life.

The exhibition offers a vision of the city as an emotional archive and a source of creative material. Over 130 photographs — many previously unpublished — portray Paris through urban micro-memories: walls, signs, courtyards, and details. Each image enters into dialogue with film fragments, objects, and visual notes, composing a continuous montage between intimacy and public space.

I'm not sure that viewers need to understand everything they see, but it is necessary that they feel.

Agnès Varda

Once outside the galleries, the city can’t help but look different.

It feels like a living organism, full of folds and crevices where the unseen hide, of sharp edges and corners teeming with life, of stains that break through the postcard surface.

As if Varda’s films — after inhabiting, filming, and crossing Paris for over sixty years — had reawakened an alternative geography beneath the tourist gloss: truer, more contradictory, more sensitive.

Agnès Varda was always a real body — a woman of flesh and blood, with her feet on the ground and her head in the edit. Her gaze on the city is the same: situated, tactile, material.

Paris is neither mythologized nor aestheticized; it’s treated like another living body — one that breathes, eats, chews, sometimes swallows, sometimes spits out.

And it is precisely in this refusal of the Parisian fetish, in this gaze that also embraces the discarded, that a deep and enduring love for the urban space is revealed.

Revisiting Varda through Paris, and Paris through Varda, is both a critical and emotional exercise.

It means descending into the city as if into a film edited by hand, and recognizing that the gaze that truly loves is the one that doesn’t look away — even when what it sees challenges our idea of beauty, love, or belonging.

To pay tribute to this gaze, we’ve imagined a six-stop itinerary that weaves together cinema and architecture, inviting us to rediscover Paris through the places that were crossed — and transformed — by the work of one of the most lucid and radical voices in auteur cinema.

Rue Daguerre – Daguerréotypes (1976)

86 rue Daguerre, 14° arrondissement

In the heart of Paris’s 14th arrondissement, rue Daguerre is not just an address — it is a key to understanding the entire poetic universe of Agnès Varda.

At number 86, in a former printing shop turned into a live-in studio, Varda lived and worked for nearly seventy years. Daguerréotypes is the most emblematic expression of this bond: a documentary filmed entirely within a hundred-meter radius of her home, a self-imposed constraint so she could stay close to her newborn son.

Its protagonists are the small shopkeepers of the street, portrayed in the daily repetition of their gestures.

Varda’s camera observes with ethnographic rigor and poetic tenderness the thresholds between private life and public space, between storefronts and backrooms, between individual identity and urban microcosm.

The modest architecture of the neighborhood thus becomes both setting and character, both structure and narrative.

Boulevards, Squares, and Parks of the Rive Gauche – Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

4 rue Huyghens, 14th arrondissement: Cléo’s apartment

128 rue de Rivoli, 1st arrondissement: hat shop

24 rue des Bourdonnais, 1st arrondissement: café

Boulevard de l’Hôpital, 13th arrondissement: final scene, Hôpital de la Salpêtrière

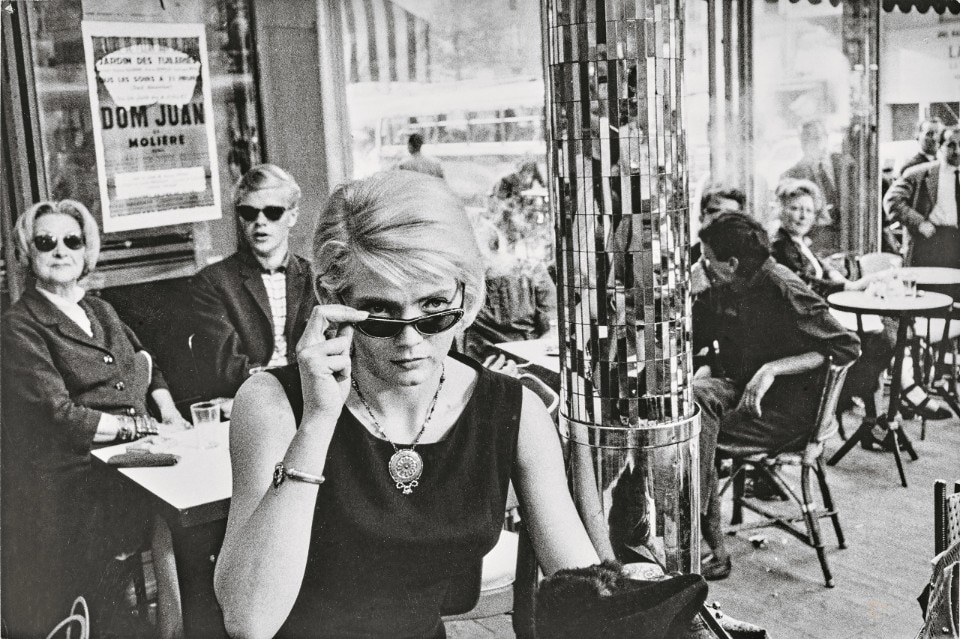

In Cléo from 5 to 7, Varda tells in real time the story of two hours in the life of a singer awaiting the results of a medical diagnosis. The film unfolds as an urban journey: Cléo moves from central cafés to crowded squares, from quiet gardens to residential neighborhoods.

The city is never a mere backdrop, but a true emotional map that mirrors the protagonist’s inner transformations. Spaces expand or contract depending on her state of mind; architecture becomes a vessel of tension or relief.

Paris appears in its most everyday dimension: no monuments, just streets to cross and people to meet. The camera walks, observes, and breathes alongside Cléo.

The Caryatids and Rue de Turbigo – Les dites cariatides & Ange de la rue de Turbigo (1984)

Boulevard Haussmann

57 rue de Turbigo, 3rd arrondissement: the statue known as the “giant angel” is the tallest caryatid in the city

In Les dites cariatides, Varda reflects on the silent yet omnipresent role of the sculpted female figures that support the façades and balconies of Parisian buildings. The caryatids become a metaphor for the female condition: seen but ignored, decorative yet immobile.

Varda films these architectural presences with delicacy and irony, transforming a seemingly neutral element into a poetic and political subject.

In Ange de la rue de Turbigo, shot on Super 8, the reflection continues on a more intimate scale: an angel carved into the façade of a bourgeois building becomes a pretext for exploring the interplay between ornament, memory, and the urban gaze.

In both works, architecture speaks — but only to those who take the time to truly look.

Peripheries, Interstices, and Absences – Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985)

Languedoc-Roussillon region: Filming took place in villages such as Bellegarde, Boulbon, Saint-Étienne-du-Grès, Générac, Jonquières-Saint-Vincent, Uchaud, Montcalm, and Tresques.

In Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond), Varda films the solitary drift of Mona, a young woman who chooses to live on the margins, without a home or ties. The film unfolds mostly in peripheral and interstitial spaces in the south of France: fallow fields, highway interchanges, greenhouses, abandoned farmhouses.

Traditional architecture is almost entirely absent; what remains are traces, remnants, signs of a denied or forgotten way of dwelling.

The city — more evoked than shown — recedes and takes shape as an excluding entity. Varda adopts a fragmented structure, composed of subjective testimonies and nonlinear glimpses, reflecting the discontinuity and social invisibility of the protagonist.

Facades as Surfaces of Memory – Faces Places (Visages Villages, 2017)

Bruay-la-Buissière, Pirou, Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer, and other villages and towns across France.

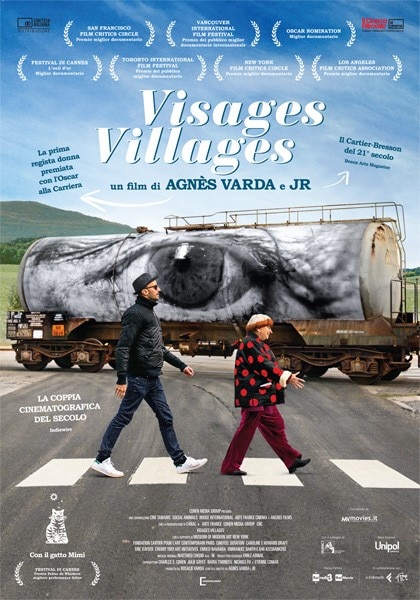

Faces Places (Visages Villages) is a documentary road movie created by Agnès Varda in collaboration with artist JR. Together, they travel across France, pasting giant photographic portraits of local residents onto walls, silos, and the façades of rural and industrial buildings.

In one of the final scenes, Varda’s own face appears on the shutter of her former studio on rue Daguerre — a gesture that is at once intimate and public, private and monumental.

Architecture becomes a narrative surface, an urban skin on which to imprint collective memory.

The film challenges the boundaries between public art and cinema, between representation and participation, turning the built environment into a living, dynamic support for meaning.

The Reconstructed City – The Beaches of Agnès (Les plages d’Agnès, 2008)

Rue Daguerre, Paris: her home and studio

Sète, France: place of her childhood

La Panne, Belgium: childhood beach

Santa Monica, Los Angeles: time spent in the United States

In this film self-portrait, Agnès Varda reconstructs fragments of her life through ephemeral installations, photographs, and improvised sets. In one of its most memorable sequences, she transforms rue Daguerre into an artificial beach: sand, umbrellas, and mirrors blend into the real pavement, blurring the line between dream and everyday life.

The home becomes a film set, and the city turns into a moving stage of memory. Architecture is reinvented as a poetic space — at once real and symbolic.

The Beaches of Agnès is a film that inhabits the places of a life and reactivates them as narrative devices. It reaffirms Varda’s deep connection to architecture and reveals her cinema as a form of emotional urbanism.