The 2026 Golden Globes have just wrapped up, crowning winners and losers alike. The familiar pagan ritual, staged amid the velvets of the Beverly Hilton in Los Angeles, dissolves into that faintly melancholic afterglow that follows every major event, leaving us to reflect on how cinema—this ‘dream machine’ born of light and dust—is nothing more than the latest, sublime metamorphosis of an ancient obsession: the desire to make an instant eternal.

Hollywood may be the temple of today’s visual liturgy. Its roots, however, lie far deeper, in the silence of cathedrals and the rigor of Renaissance panels, where painting had already anticipated editing, close-ups and narrative tension. There is no shot today that moves us which was not first imagined by a brush in the twilight of a fifteenth-century workshop, transforming vision into a ruthless and beautiful form of knowledge.

In today’s so-called ‘revolutionary’ shots, the influence of Masaccio, Piero della Francesca and Mantegna is unmistakable: giants who required no frames per second to suggest movement, having mastered the art of igniting stillness.

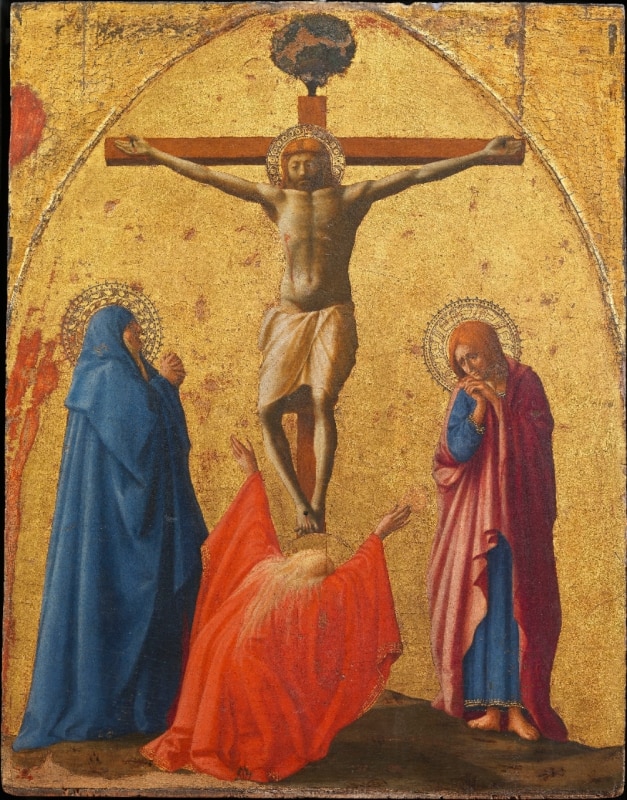

Let us begin with Masaccio’s Crucifixion in Capodimonte. At the foot of the cross, the figure of Mary Magdalene erupts onto the scene: a vermilion form screaming with her back turned to us, a gesture so absolute, so radical, it feels almost scandalous. We never see her face, yet we grasp the full abyss of her anguish solely through the desperate geometry of her raised arms. It is the very essence of silent cinema, where emotion cannot rely on words and must become muscle, nerve and posture. Here Masaccio invents the first “close-up of the soul” without ever framing a face, entrusting the body’s language with the task that decades later would belong to an expressionist actress under the glare of arc lights.

If Masaccio gives us the raw cry, Piero della Francesca provides the cut.

There is no framing that moves us today that has not already been dreamed up by a brush in the twilight of a fifteenth-century workshop.

In the Flagellation of Christ in Urbino, the scene splits into a spatial dialectic that anticipates, by centuries, the deep focus of an Orson Welles. Perspective is not a mathematical cage but a temporal sequence: on the left, deep within a classical portico, Christ’s torture unfolds in a suspended, almost metaphysical time; on the right, in the foreground, three men converse about business or politics, indifferent to the sacred drama. This perspectival rift creates a purely cinematic narrative sequence. The viewer’s eye is forced to ‘edit’ the two scenes, leaping from the particular to the universal, experiencing the simultaneity of two worlds that brush past one another without ever meeting. It is the lesson of great auteur cinema: the highest tension lies not in action itself, but in the gap between those who suffer from those who look away.

And finally, to understand how an image can become a clue, one must turn to Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, to that violently foreshortened body that still takes our breath away. But it is at the margins that the drama takes on the qualities of a mystery, in the noblest and most investigative sense of the word. Look at the mourners on the left: the Magdalene’s mouth, barely suggested, reduced to a whisper of color between wrinkles carved by tears. In that micro-fracture, in that almost invisible detail, lies the keystone of the entire narrative. It is the detail that makes the difference, the clue the attentive viewer must catch to decipher the enigma of death. As in a suspense film—where a reflection in a glass or a fleeting eye movement reveals the truth before dialogue does—Mantegna shows us that the secret of a story is not always at its center, but in the ruthless precision of a peripheral detail.

As the lights of the Golden Globes fade and the statuettes are put away, one realization remains: every great director does little more than restage these ancient, immortal intuitions. Cinema, in the end, has invented nothing the human eye had not already learned amid the chiaroscuro of the Renaissance. Every new frame is an echo, every camera movement an unconscious homage to those forefathers who, by fixing a single instant in pigment, taught us how to watch the eternal flow of life. And so, between the glamour of a Californian night and the silence of a picture gallery, the circle closes on a single, endless quest for beauty.

Opening image: Andrea Mantegna, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, c. 1470-1474 or c. 1483. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons