“Machines à penser”, the exhibition at the Prada Foundation, which takes place in the context of the International Art Exhibition in Venice, focuses on an elemental architectural element with wide-ranging symbolic implications: the hut. The project is the result of an intellectual examination of the theme of the mind and of culture and, more in particular, on the relationship between space and thought, between the act of inhabiting and philosophical reflection. A relationship which is perceivable in the fact that various fundamental figures in 20th century philosophy, all with German origins in common, lived, either by choice or under obligation, in conditions of exile, flight and displacement: Martin Heidegger (1889-1976), Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889 1951) and Theodor W. Adorno (1903-1969).

View gallery

View gallery

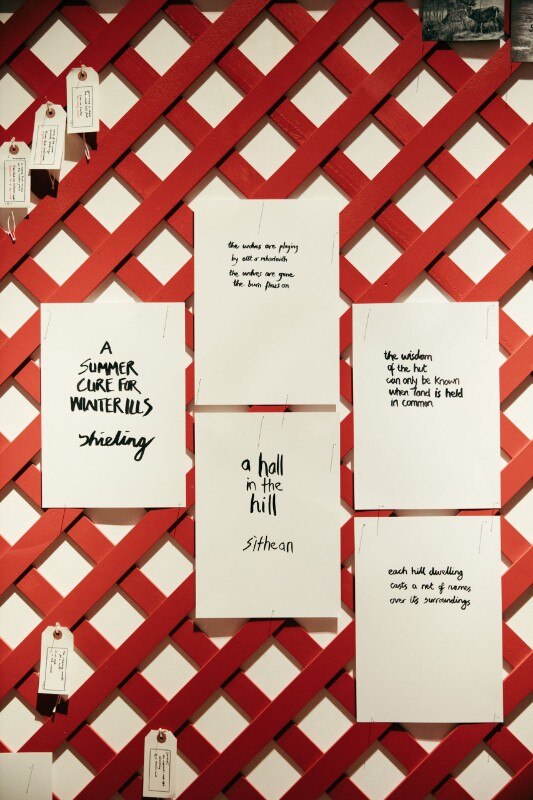

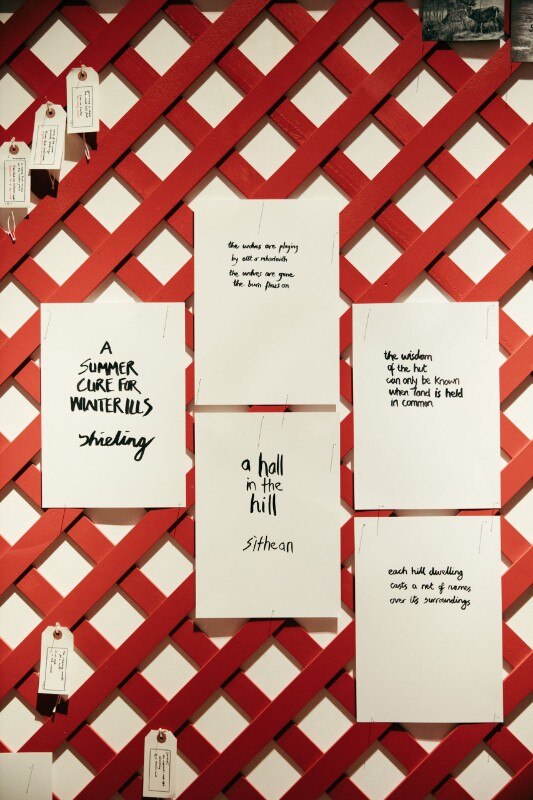

The curator Dieter Roelstraete focuses on physical or mental places which favoured these great thinkers in their reflection and intellectual production. In particular, the project concentrates on the cabins that two of them, Heidegger and Wittgenstein, had built in locations that were to some extent distant from the city, and in which they wrote their respective fundamental works, as well as on the dimension of distance and displacement experienced by the third of them, Adorno, during his years in exile in Los Angeles. For the latter, the dimension of the hut is brought into focus in Adorno’s Hut, a work in the shape of a small wooden and metal house by the Scottish artist Ian Hamilton Finlay, who in turn, in 1987, decided to isolate himself in a remote area of the country, and managed his own garden as though it were a city-state.

The situations experienced by Heidegger, who was unrepentantly in favour of Nazism, and by Wittgenstein and Adorno, both from cosmopolitan Jewish families, therefore differed greatly. As Roelstraete maintains in the exhibition catalogue, for Heidegger the cabin, which was beyond and above the nanism of ordinary life, “was not only a philosophical idea in wood and stone, but also a rhetoric device as well as a performance”. This was not the case for Wittgenstein, whose life consisted in a series of flights due to an internal need, and whose refuge, situated in a fjord in Skjolden, Norway, was effectively extreme, neither by any means was it the case for Adorno, whose exile was due to Nazi persecution.

View gallery

View gallery

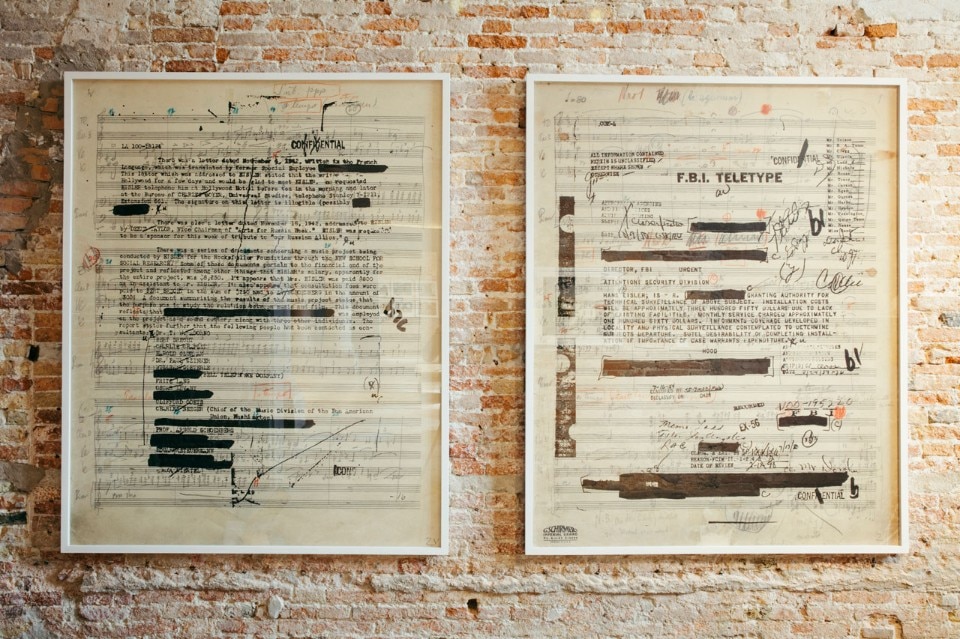

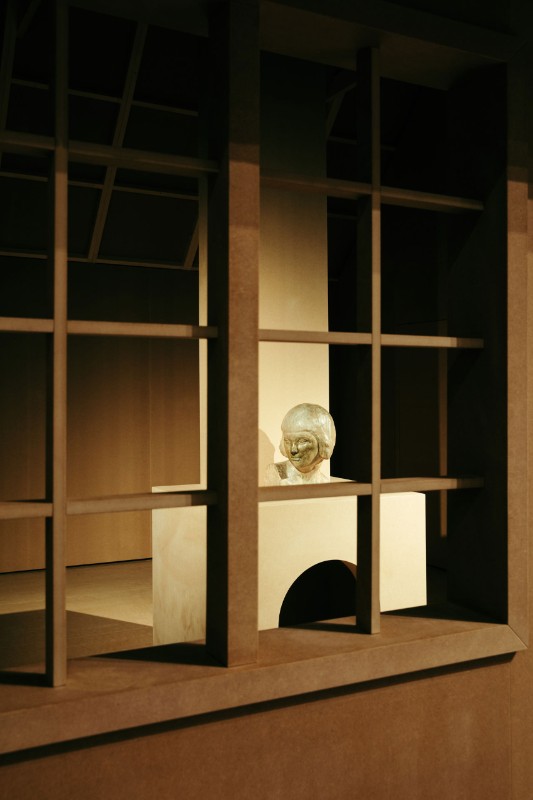

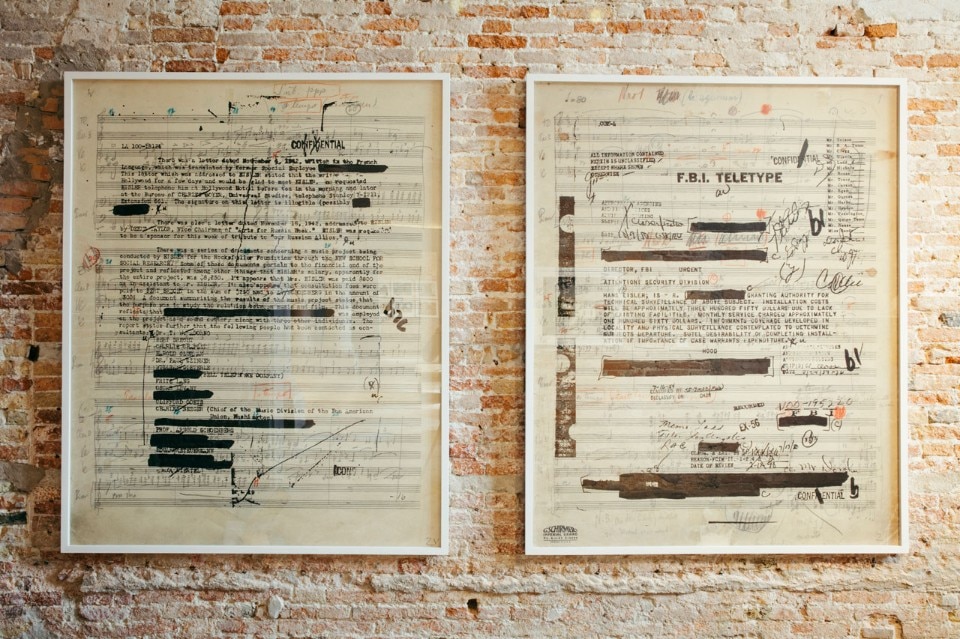

The exhibition begins with these references. In the centre, we find a reproduction of the two refuges of Heidegger and Wittgenstein, while for Adorno, his concentration space is linked, if anything, to music, his great passion. This is why, as well as Adorno’s Hut by Finlay, on the main floor of the building together with the other two huts, there is the large sound installation by Susan Philipsz Part File Score, accompanied by a large photograph by Patrick Lakey showing the interior of Villa Aurora in Los Angeles, which served as a place for the exchange of ideas for the philosopher and the community of intellectual defectors which formed in the city during the period of the Third Reich. The exhibition continues through references and chains of meaning, and includes other works, in more or less stringent relation to the three philosophers and the idea of distance and isolation. There are three vases in terracotta, porcelain and rubber, specially made for the exhibition by Goshka Macuga. They represent the heads of the three philosophers, and sprout plants and flowers.

View gallery

View gallery

Anselm Kiefer made a sculpture produced through dialogue with the cinematographer and writer Alexander Kluge, who was close to Adorno in the final years of his post at the Frankfurt School; Kluge, in turn, produced for the exhibition a video which focuses on his recollection of Adorno’s passion for the cinema.

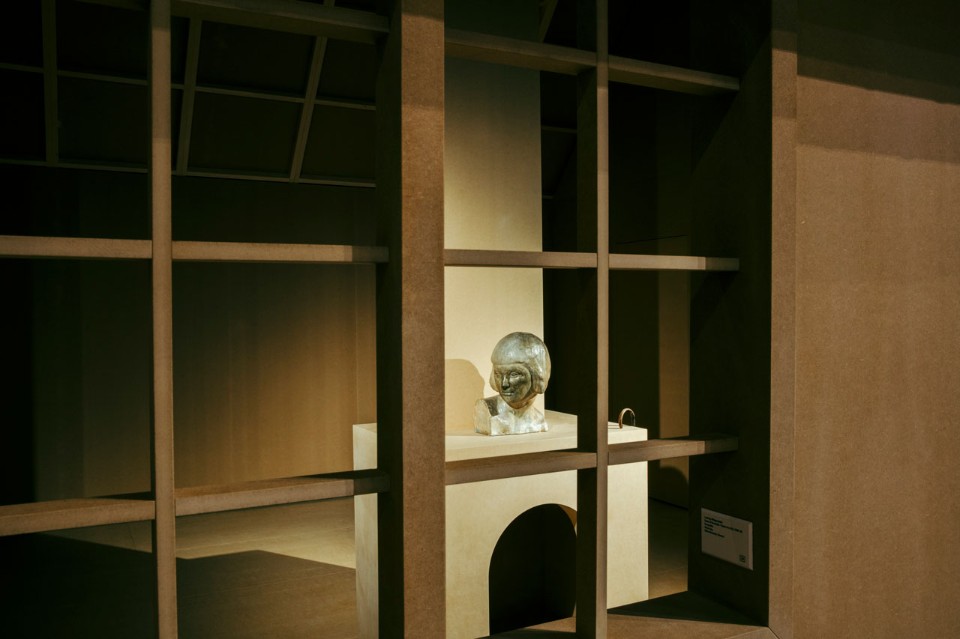

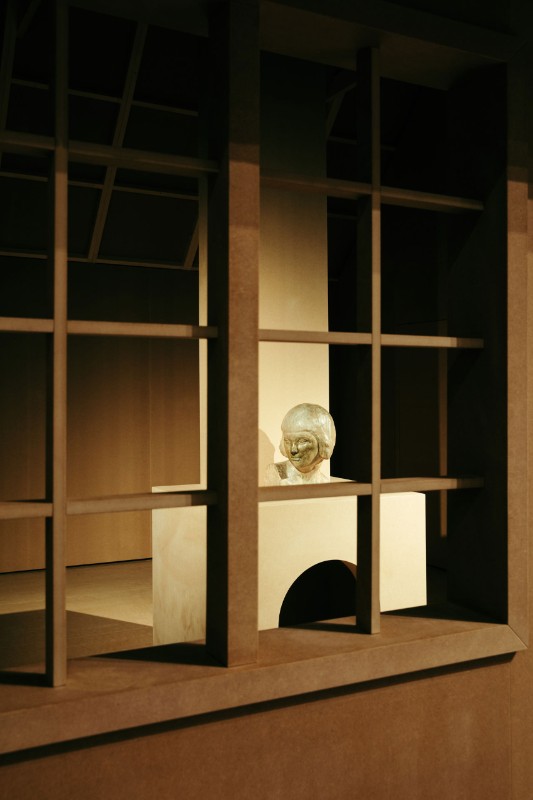

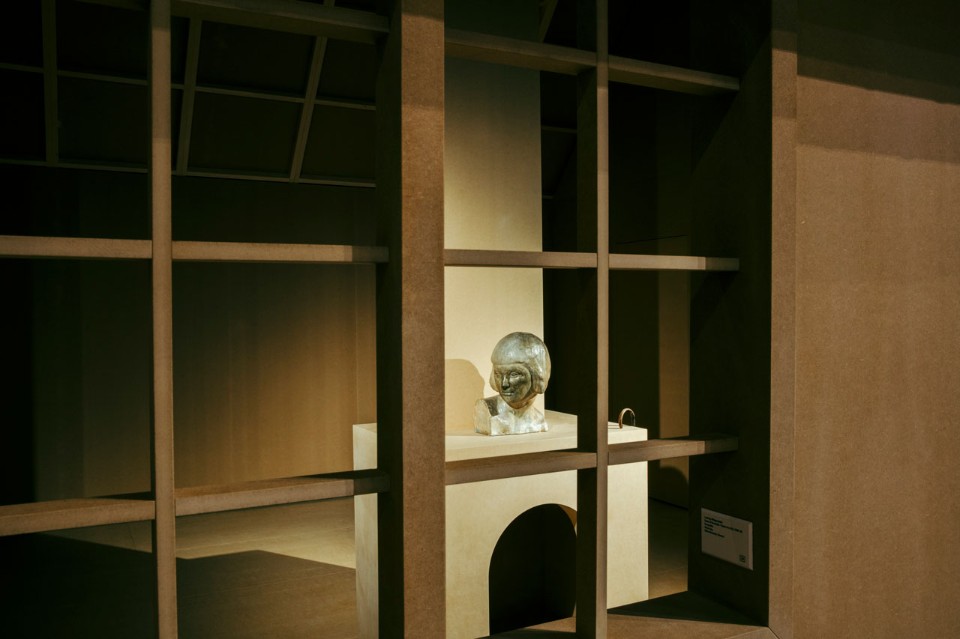

There are also a number of objects which widen the semantic and temporal field of reference. A historical section examines the figure of the hermit, focusing on the legend of the father of the Church of Saint Jerome, who lived between the 4th and 5th centuries. A part of the Renaissance paintings and prints regarding the saint are shown within a small Renaissance study in wood inlay, another extraordinary symbol of the need for retreat and the desire to escape from the pressure of daily life and immerse oneself in concentration on thought and study. The study contains rare editions of works by Heidegger and Wittgenstein.

Through mutations of meaning and cross references, this rarefied exhibition is imbued with the tensions of history and the irremediable contradictions of thought. Thus, for example, in Heidegger’s house, we find photographs taken in Todtnauberg between 196 and 1968 by the photojournalist - of Jewish descent - Digne Meller-Marcovicz. The exhibition does not explicitly reveal any more than this; but a muffled cry lies just below the surface, and it becomes ever stronger as one ventures further into the labyrinth of references.

“Machines à penser” is a challenge, an exhibition which requires preparation and offers growing satisfaction to those who are able to interpret the dense interweaving of subtexts. Not only is the theme of anxiety of flight and internal exile extremely meaningful, but the very fact that it is presented in such a period of cultural flatness, scenographic exhibitions and populism is in itself a statement.

- Exhibition title:

- Machines à penser

- Opening dates:

- 23 May – 25 November 2018

- Curator:

- Dieter Roelstraete

- Venue:

- Fondazione Prada, Ca’ Corner della Regina, Venezia