If, according to Rem Koolhaas since the 2014 Venice Biennale, the bathroom is ”the fundamental zone of interaction – at the most intimate level – between man and architecture”, it is not surprising that the design theme of the public restrooms, exporting such intimate interaction to the streets and squares of a city, is particularly challenging.

That of the public toilet is an ancient history that goes from the time of Vespasian – when public urinals were used to collect the ammonia from urine used in textile manufacturing, to tax it – to when, from the 19th century onwards, restrooms became an expression of urban decorum (furnishings in the time of Haussmann and sanisettes in Paris, public baths at the Graben in Vienna and the Albergo Venezia in Milan).

The ways in which the subject of public baths is approached vary according to latitudes: among the most virtuous in terms of respect for the individual and for public affairs are the Scandinavian countries and especially Japan, where the sentō (the typical public bath with water pools) has for centuries offered opportunities for socialising and cathartic experiences of relaxation.

In general, beyond the mere function of regulating physiological needs in the street, the public bath is an element that transcends urban furniture to become an expression of culture and human dignity. This is demonstrated by a number of contemporary works around the world: from those rooted in an established tradition (The Tokyo Toilet project, transposed to the Triennale) to impromptu ones (Aandeboom); from those integrated into the historical or landscape context (Miró Rivera Architects, Diego Jobell, Snøhetta, Schleifer & Milczanowski Architekci, Manthey Kula Architects) to those openly exhibited (Gramazio & Kohler, Chris Briffa); from dreamlike ones (Hundertwasser) to those with political (Cassani, Galán, Munuera and Sanders) and social (RC architects) significance.

In any case, net of “structural” idiosyncrasies (due to neglect and decay known in our country) and psychological idiosyncrasies (related to germaphobia, claustrophobia and pathologies of various kinds), there remains the common denominator of the bathroom as a space for the care and government of our bodies, which, whether in the home or in a square, is perhaps the only real ”throne room” we have.

The architecture of public toilets, from antiquity to present-day projects

Often mistreated for their prosaic nature, public restrooms represent civic sense and urban culture, and provide a point of connection between man and architecture in the city.

View gallery

View gallery

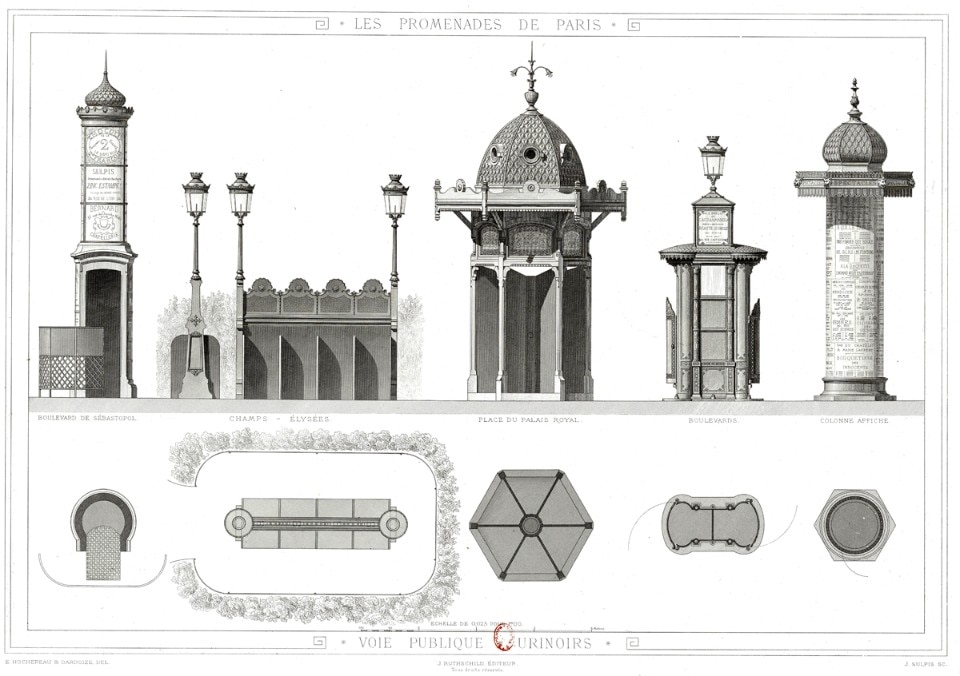

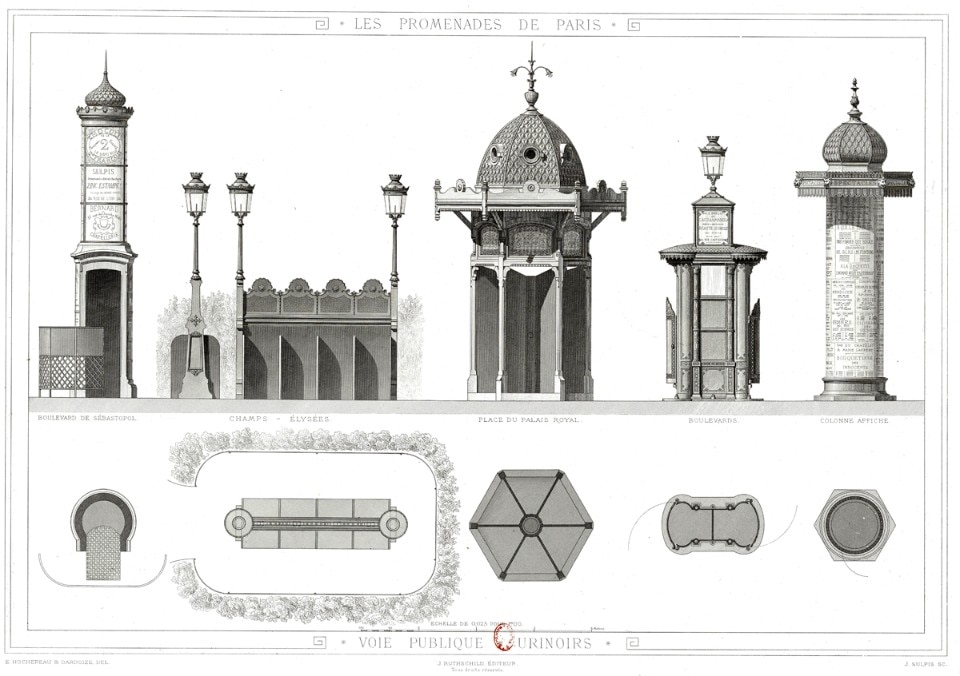

Urban furniture (urinals) in the time of Haussmann, Paris, France 19th century

At the time of the Second Empire, Paris underwent a profound transformation that, at the behest of Napoleon III and thanks to Baron Haussmann, involved all areas of urban planning, from road planning to infrastructure, to urban decoration and furnishings. Among the latter were the public toilets, which, over time, evolved in technology and efficiency, giving way from the 1980s onwards to the 'sanisettes', typical automatic toilets distributed (there are more than 400) throughout the city.

Urban furniture (sanisettes), Paris, France 19thcentury

Piero Portaluppi, Albergo Diurno Venezia, Milan, Italy 1926

The Albergo Diurno Metropolitano 'Venezia' in Piazza Oberdan, closed to the public since 2003 and managed by the FAI since 2016, is an Art Deco jewel still awaiting a project to return it to public use.

Piero Portaluppi, Albergo Diurno Venezia, Milan, Italy 1926

Public restrooms at the Graben, Vienna, Austria 1905

In a lively Graben square, Jugendstil lampposts mark the underground public baths still in use today, which are accessed via two separate staircases and contain original oak doors and brass washbasins.

Public restrooms at the Graben, Vienna, Austria 1905

Friendensreich Hundertwasser, Kawakawa Toilets, Kawakawa, New Zealand 1999

Photo Berlin-George from Wikipedia

With its undulating forms, irregular ceramic tiles, stained glass and a tree incorporated into the construction, this public bathroom in northern New Zealand is a manifesto of the Austrian master's language.

Friendensreich Hundertwasser, Kawakawa Toilets, Kawakawa, New Zealand 1999

Photo Phil Whitehouse from Wikimedia Commons

Miró Rivera Architects, Trail restroom, Austin, Texas, USA 2007

Located within the Lady Bird Lake Hike and Bike Trail linear park along the Colorado River, the first public restroom to be built on the site is a sculptural volume consisting of forty-nine slabs of cortén steel, staggered in plan and of varying sizes, to ensure intimacy while facilitating the flow of natural light and ventilation.

Miró Rivera Architects, Trail restroom, Austin, Texas, USA 2007

Snøhetta, Eggum Tourist route, Lofoten, Norway 2007

Included in the circuit of 18 national tourist routes to promote the enjoyment of Norway's spectacular landscape by providing services, walking paths and public artworks, the project in remote Lofoten includes a hiking trail, a car park and a service building set in an amphitheatre and clad with locally reclaimed wood.

Snøhetta, Eggum Tourist route, Lofoten, Norway 2007

Diego Jobell, Public Restroom, Rosario, Argentina 2009

The service building located in Urquiza Park houses a public restroom, a belvedere and a children's playground: the green roof minimises the insertion of the exposed concrete and U-glass construction into the natural context while, in the interior, cement and galvanised sheet metal are used to prevent vandalism and reduce the need for maintenance.

Diego Jobell, Public Restroom, Rosario, Argentina 2009

Chris Briffa, Norbert Attard, Strait Street Toilet, Valletta, Malta 2010

The public toilets with their eye-catching design of bright colours that invite one in, reflective surfaces that amplify the space, neon light and curtain-shaped mirrors reminiscent of cabaret shows, cheerfully evoke the capital's sizzling nightlife.

Chris Briffa, Norbert Attard, Strait Street Toilet, Valletta, Malta 2010

Aandeboom, P-TREE, Roskilde Festival, Denmark 2011 (temporary installation)

As part of the Roskilde Festival, urinals hanging from trees and made of rotationally moulded plastic were installed to prevent visitors' bodily urgency. The urinals can be connected to the main sewage system or to a tank with a pump.

Aandeboom, P-TREE, Roskilde Festival, Denmark 2011 (temporary installation)

Gramazio & Kohler, Public restroom, Uster, Switzerland 2011

The public toilet, conceived as a prototype for a new urban infrastructure and characterised by a parametric façade design, consists of folded, vertically arranged coloured aluminium strips. The depth of the aluminium shapes and the different angle of light reflection, in combination with the slightly different colours of the strips, generate an iridescent effect depending on the time of day and the position of the observer.

Gramazio & Kohler, Public restroom, Uster, Switzerland 2011

Schleifer & Milczanowski Architekci, Old Town Public toilets, Gdańsk, Poland 2012

The work interprets the need for multifunctional street furniture in the heart of the historic town: the drop-shaped volume is composed of a prefabricated steel structure and rust-coloured coated sheet metal panels that suggest an association with the rough hulls of ships from neighbouring shipyards. The exterior has vertical ribs in striated steel that serve as bicycle racks.

Schleifer & Milczanowski Architekci, Old Town Public toilets, Gdańsk, Poland 2012

Manthey Kula Architects, Roadside Reststop Akkarvikodden, Lofoten Islands, Norway 2016

If at a latitude above the Arctic Circle, along the Lofoten Islands Tourist Road nestled between sea and mountains, the previous small service building has been blown away by the wind, the one that replaces it is a minimalist, windowless cortén steel structure to give visitors a break from the strong sensory experience of the extreme landscape outside.

Manthey Kula Architects, Roadside Reststop Akkarvikodden, Lofoten Islands, Norway 2016

RC architects, Light Box Restroom, Mumbai, India 2016

Located on the side of a busy highway in the Mumbai metropolitan area and conceived exclusively for women, the complex consists of three restrooms and a nursery and is articulated around a treed patio that serves as a place for socialising and a temporary art gallery. The use of durable materials with minimal maintenance requirements - from the walls made of aluminium composite panels and stainless steel sheets, to the polyurethane in the floors - makes it a functional but no less welcoming space.

RC architects, Light Box Restroom, Mumbai, India 2016

Cassani, Galán, Munuera and Sanders, Restroom Pavilion, Giardini della Biennale, Venice, Italy 2021 (temporary installation)

At the Giardini and at the Arsenale, as part of the '21 Venice Biennale, the theme of the bathroom was addressed in an ideological key, as a symbolic space for the conquest of human rights and ecological awareness. At the Giardini, in particular, the theme was declined in the redesigning of one of the public toilets, ennobled in the same way as the other pavilions: "The Restroom Pavilion" is announced by a series of flags instead of the traditional signage and shows a system of pipes and drains in the foreground.

The Tokyo Toilet (exhibition), Milan Triennale, Milan, Italy 2022 (temporary installation)

As part of the Triennale di Milano 2022, an installation presents thirteen 1:1 scale segments of the toilets included in "The Tokyo Toilet" project, launched in Tokyo on the occasion of the 2020 Olympics and characterised by the creation of public toilets, signed by internationally renowned architects, located in 17 places in Shibuya. As in the original project, the Milan exhibition intends to overturn the commonplace of the public toilet and redefine its perception in the collective imagination, thanks to a functional yet welcoming design.

Urban furniture (urinals) in the time of Haussmann, Paris, France 19th century

At the time of the Second Empire, Paris underwent a profound transformation that, at the behest of Napoleon III and thanks to Baron Haussmann, involved all areas of urban planning, from road planning to infrastructure, to urban decoration and furnishings. Among the latter were the public toilets, which, over time, evolved in technology and efficiency, giving way from the 1980s onwards to the 'sanisettes', typical automatic toilets distributed (there are more than 400) throughout the city.

Urban furniture (sanisettes), Paris, France 19thcentury

Piero Portaluppi, Albergo Diurno Venezia, Milan, Italy 1926

The Albergo Diurno Metropolitano 'Venezia' in Piazza Oberdan, closed to the public since 2003 and managed by the FAI since 2016, is an Art Deco jewel still awaiting a project to return it to public use.

Piero Portaluppi, Albergo Diurno Venezia, Milan, Italy 1926

Public restrooms at the Graben, Vienna, Austria 1905

In a lively Graben square, Jugendstil lampposts mark the underground public baths still in use today, which are accessed via two separate staircases and contain original oak doors and brass washbasins.

Public restrooms at the Graben, Vienna, Austria 1905

Friendensreich Hundertwasser, Kawakawa Toilets, Kawakawa, New Zealand 1999

With its undulating forms, irregular ceramic tiles, stained glass and a tree incorporated into the construction, this public bathroom in northern New Zealand is a manifesto of the Austrian master's language.

Photo Berlin-George from Wikipedia

Friendensreich Hundertwasser, Kawakawa Toilets, Kawakawa, New Zealand 1999

Photo Phil Whitehouse from Wikimedia Commons

Miró Rivera Architects, Trail restroom, Austin, Texas, USA 2007

Located within the Lady Bird Lake Hike and Bike Trail linear park along the Colorado River, the first public restroom to be built on the site is a sculptural volume consisting of forty-nine slabs of cortén steel, staggered in plan and of varying sizes, to ensure intimacy while facilitating the flow of natural light and ventilation.

Miró Rivera Architects, Trail restroom, Austin, Texas, USA 2007

Snøhetta, Eggum Tourist route, Lofoten, Norway 2007

Included in the circuit of 18 national tourist routes to promote the enjoyment of Norway's spectacular landscape by providing services, walking paths and public artworks, the project in remote Lofoten includes a hiking trail, a car park and a service building set in an amphitheatre and clad with locally reclaimed wood.

Snøhetta, Eggum Tourist route, Lofoten, Norway 2007

Diego Jobell, Public Restroom, Rosario, Argentina 2009

The service building located in Urquiza Park houses a public restroom, a belvedere and a children's playground: the green roof minimises the insertion of the exposed concrete and U-glass construction into the natural context while, in the interior, cement and galvanised sheet metal are used to prevent vandalism and reduce the need for maintenance.

Diego Jobell, Public Restroom, Rosario, Argentina 2009

Chris Briffa, Norbert Attard, Strait Street Toilet, Valletta, Malta 2010

The public toilets with their eye-catching design of bright colours that invite one in, reflective surfaces that amplify the space, neon light and curtain-shaped mirrors reminiscent of cabaret shows, cheerfully evoke the capital's sizzling nightlife.

Chris Briffa, Norbert Attard, Strait Street Toilet, Valletta, Malta 2010

Aandeboom, P-TREE, Roskilde Festival, Denmark 2011 (temporary installation)

As part of the Roskilde Festival, urinals hanging from trees and made of rotationally moulded plastic were installed to prevent visitors' bodily urgency. The urinals can be connected to the main sewage system or to a tank with a pump.

Aandeboom, P-TREE, Roskilde Festival, Denmark 2011 (temporary installation)

Gramazio & Kohler, Public restroom, Uster, Switzerland 2011

The public toilet, conceived as a prototype for a new urban infrastructure and characterised by a parametric façade design, consists of folded, vertically arranged coloured aluminium strips. The depth of the aluminium shapes and the different angle of light reflection, in combination with the slightly different colours of the strips, generate an iridescent effect depending on the time of day and the position of the observer.

Gramazio & Kohler, Public restroom, Uster, Switzerland 2011

Schleifer & Milczanowski Architekci, Old Town Public toilets, Gdańsk, Poland 2012

The work interprets the need for multifunctional street furniture in the heart of the historic town: the drop-shaped volume is composed of a prefabricated steel structure and rust-coloured coated sheet metal panels that suggest an association with the rough hulls of ships from neighbouring shipyards. The exterior has vertical ribs in striated steel that serve as bicycle racks.

Schleifer & Milczanowski Architekci, Old Town Public toilets, Gdańsk, Poland 2012

Manthey Kula Architects, Roadside Reststop Akkarvikodden, Lofoten Islands, Norway 2016

If at a latitude above the Arctic Circle, along the Lofoten Islands Tourist Road nestled between sea and mountains, the previous small service building has been blown away by the wind, the one that replaces it is a minimalist, windowless cortén steel structure to give visitors a break from the strong sensory experience of the extreme landscape outside.

Manthey Kula Architects, Roadside Reststop Akkarvikodden, Lofoten Islands, Norway 2016

RC architects, Light Box Restroom, Mumbai, India 2016

Located on the side of a busy highway in the Mumbai metropolitan area and conceived exclusively for women, the complex consists of three restrooms and a nursery and is articulated around a treed patio that serves as a place for socialising and a temporary art gallery. The use of durable materials with minimal maintenance requirements - from the walls made of aluminium composite panels and stainless steel sheets, to the polyurethane in the floors - makes it a functional but no less welcoming space.

RC architects, Light Box Restroom, Mumbai, India 2016

Cassani, Galán, Munuera and Sanders, Restroom Pavilion, Giardini della Biennale, Venice, Italy 2021 (temporary installation)

At the Giardini and at the Arsenale, as part of the '21 Venice Biennale, the theme of the bathroom was addressed in an ideological key, as a symbolic space for the conquest of human rights and ecological awareness. At the Giardini, in particular, the theme was declined in the redesigning of one of the public toilets, ennobled in the same way as the other pavilions: "The Restroom Pavilion" is announced by a series of flags instead of the traditional signage and shows a system of pipes and drains in the foreground.

The Tokyo Toilet (exhibition), Milan Triennale, Milan, Italy 2022 (temporary installation)

As part of the Triennale di Milano 2022, an installation presents thirteen 1:1 scale segments of the toilets included in "The Tokyo Toilet" project, launched in Tokyo on the occasion of the 2020 Olympics and characterised by the creation of public toilets, signed by internationally renowned architects, located in 17 places in Shibuya. As in the original project, the Milan exhibition intends to overturn the commonplace of the public toilet and redefine its perception in the collective imagination, thanks to a functional yet welcoming design.

-

Sections