Between 1960 and 1980, Alberto Salvati and Ambrogio Tresoldi livened up the Milanese cultural scene, bringing the art and architecture confluence to the centre of their research. Known for the use of colour, key element of their work, their projects were systematically published in Domus when its executive director was Gio Ponti, who had already promoted the principle of interdisciplinarity in the magazine since the early 1930s, suggesting collaboration between architects, artists, craftsmen and art industries. Ponti, who would remain Domus’s executive director until his death in 1979, had understood these two architects’ work design force, as the result of their research on the evolution of the living cell.

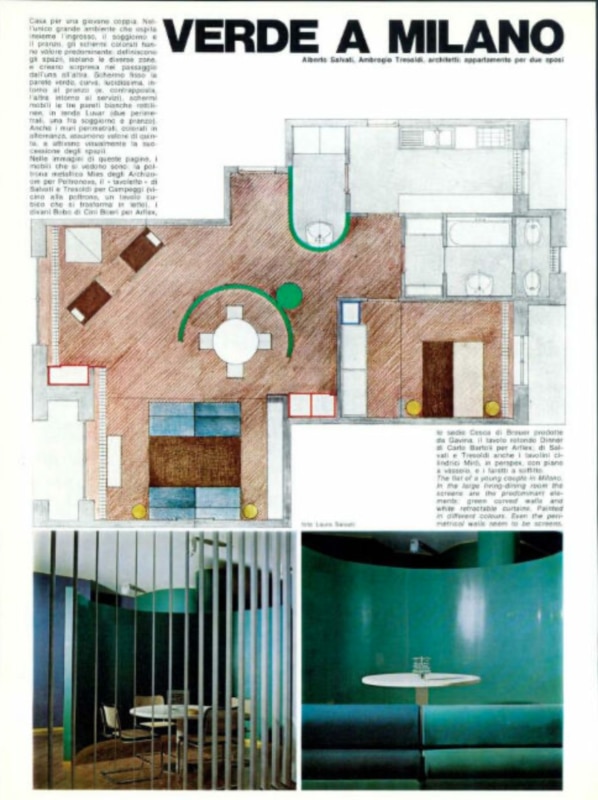

In fact, Salvati and Tresoldi’s design thought was born from a critique of the living cell idea in modern architecture. Graduated in 1960, the two had studied at Milan Polytechnic with Carlo De Carli, promoter of the primary space concept, the fundamental space for the individual to live in. Their research stems from the confutation of the rationalist movement principles and, in particular, of Le Corbusier’s living machine. From these principles, Salvati and Tresoldi began to think about a new concept of architecture, which goes beyond the functionalist limits of rationalism towards the inclusion of the spiritual aspects’ immateriality in architectural design. The interior spaces they designed were spaces of freedom, not spaces of refuge, not machines, nor dungeons, but stages open to show the everyday life. We met the architect Salvati, after more than fifty years, to ask him questions, never asked before, about their work.

What projects and themes did you bring to the magazine?

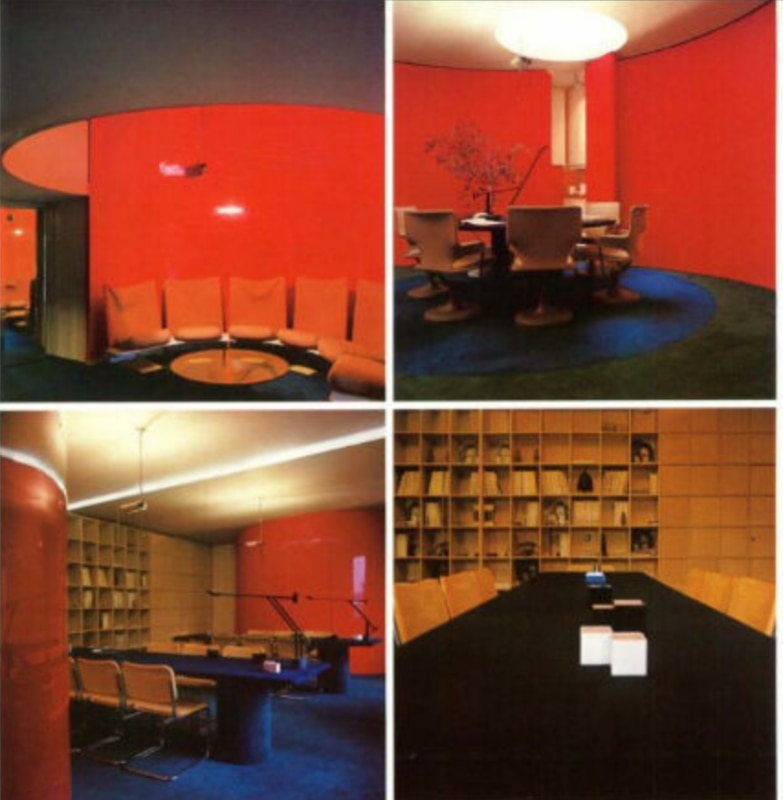

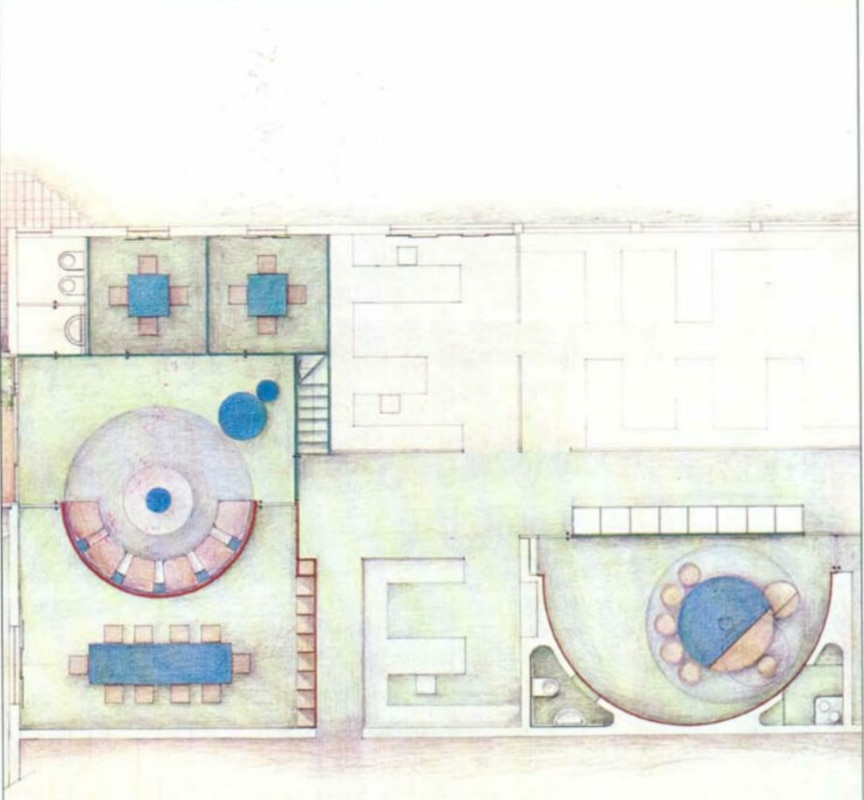

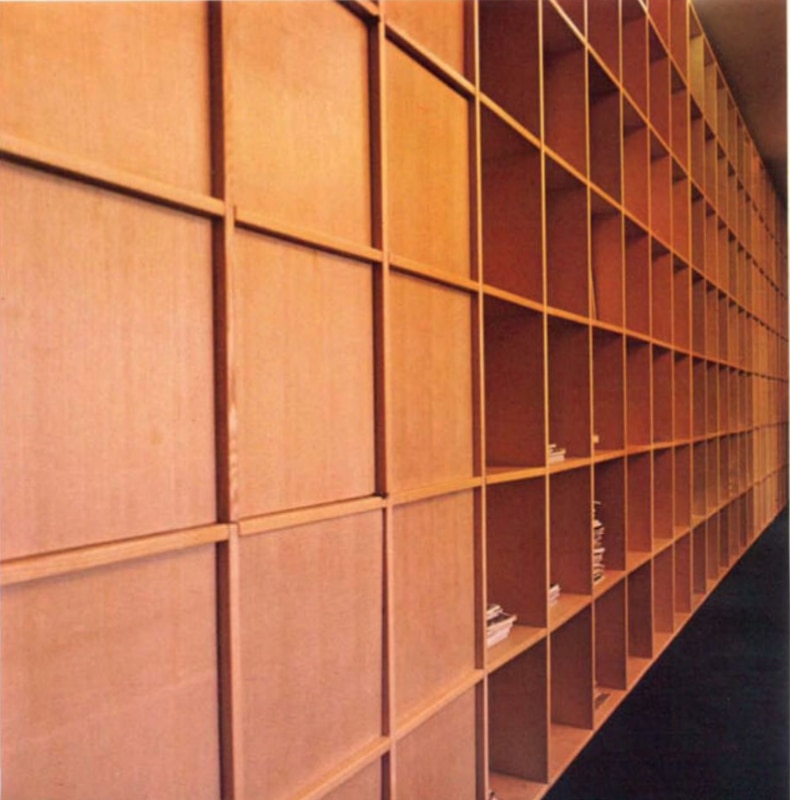

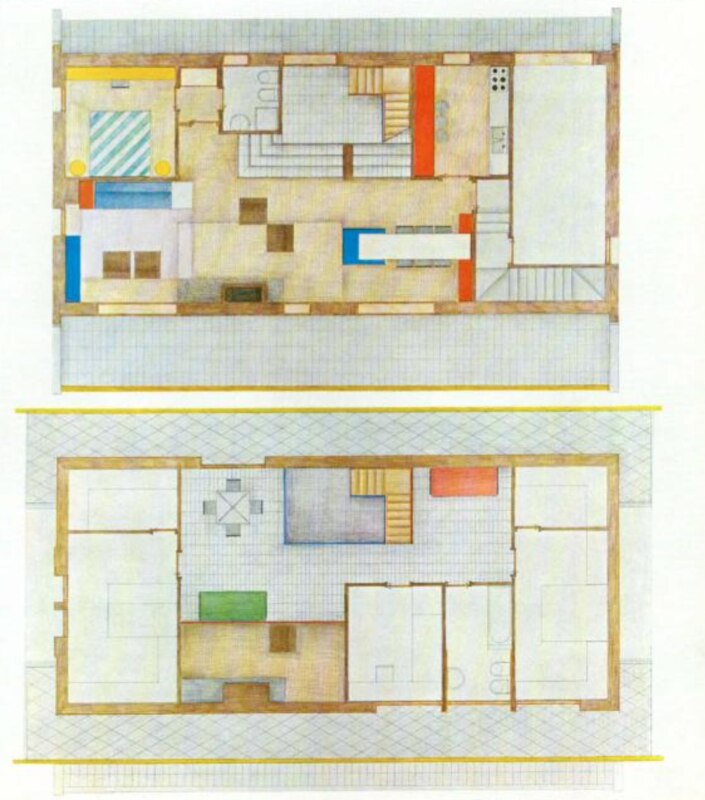

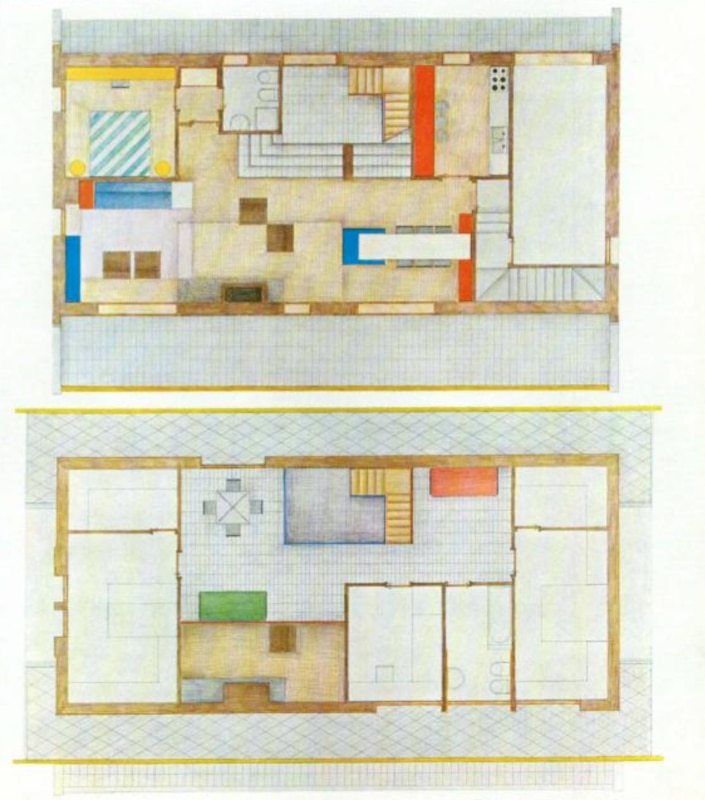

The ones we presented in Domus were mainly projects for the upper middle class, but our research aimed at rethinking the spaces of social housing. In those years, in Lissone, the Lissone Weeks took place every two years, seven days in which the city became an open-air museum and design and furnishing objects were exhibited. In 1961, immediately after our graduation, we were tasked to coordinate the Lissone Week for the home. Then, every two years, in conjunction with the Lissone Art Prize, our engagement with the Lissone Furniture Council continued until the 1970s. In the meantime, our interest in problems related to interior space in architecture had led us to publish a research on Italian furniture centres and their ability to interfere with what was being produced in the architectural field, along with another group of designers, including Renzo Piano. Discussions were held on how furniture centres could create furnishing devices that could be integrated with the living space. So, we started working on projects in which furniture was integrated with the space, which was one of the most discussed topics on Domus and of which Gio Ponti was the promoter. Then, these studies were really implemented in popular contexts when we created two complexes for the Istituto Autonomo Case Popolari (IACP).

The public construction has been a central topic in your work.

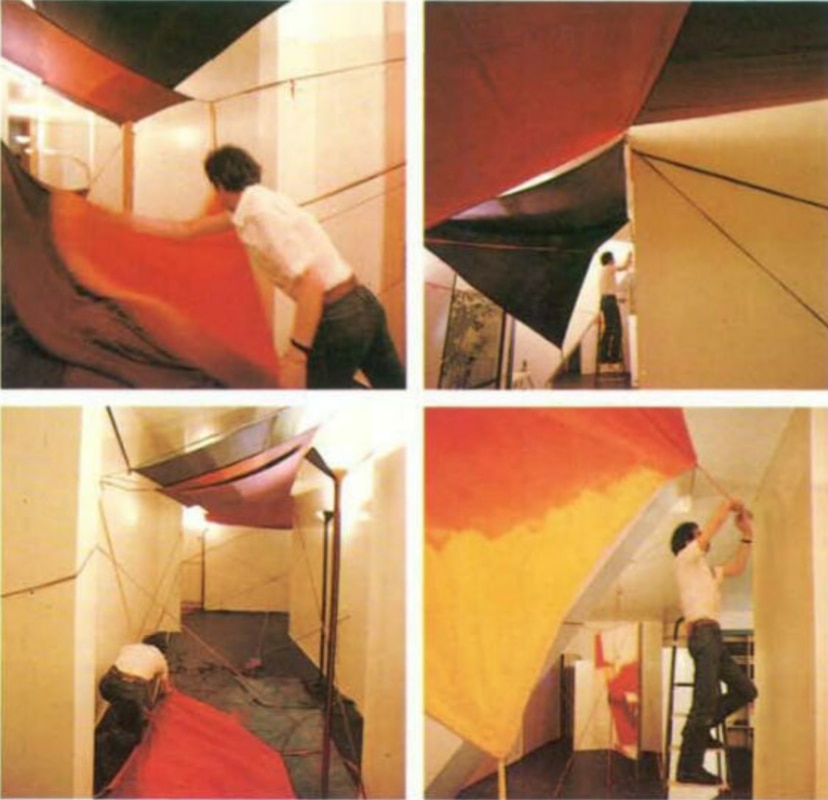

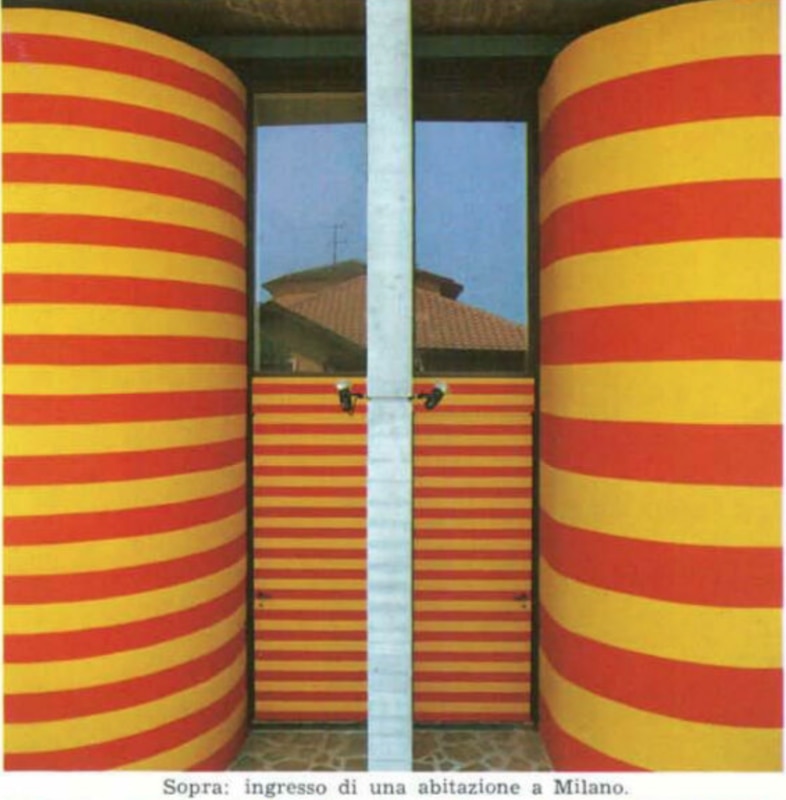

Yes, it has. In 1973, these experiments conducted along with the Faculty of Architecture were brought to the Triennial, in Milan, when we coordinated and set up the exhibition Spazio abitativo nell’edilizia pubblica for the 15th edition at the Palazzo dell’Arte. On display, we showed some examples of how the use of elements different from those of the architectural discipline benefited its users, namely the use of colour and the collaboration with artists. Ours was a way of working on an equal footing where all disciplines had equal importance in the project, we started from the old synthesis of integration of the arts and interpreted it in our own way in order to create a project that was a unified whole in which the various knowledge converged. Gio Ponti had come to see the exhibition, interested in the projects carried out for the renewal of the habitat according to what we were producing along with the artists, in the use of colour as a building material and in the resulting planimetric transformations. Speech that remained central in Domus until the 1980s.

Colour was a key element of your work. Was it wanted? If so, why?

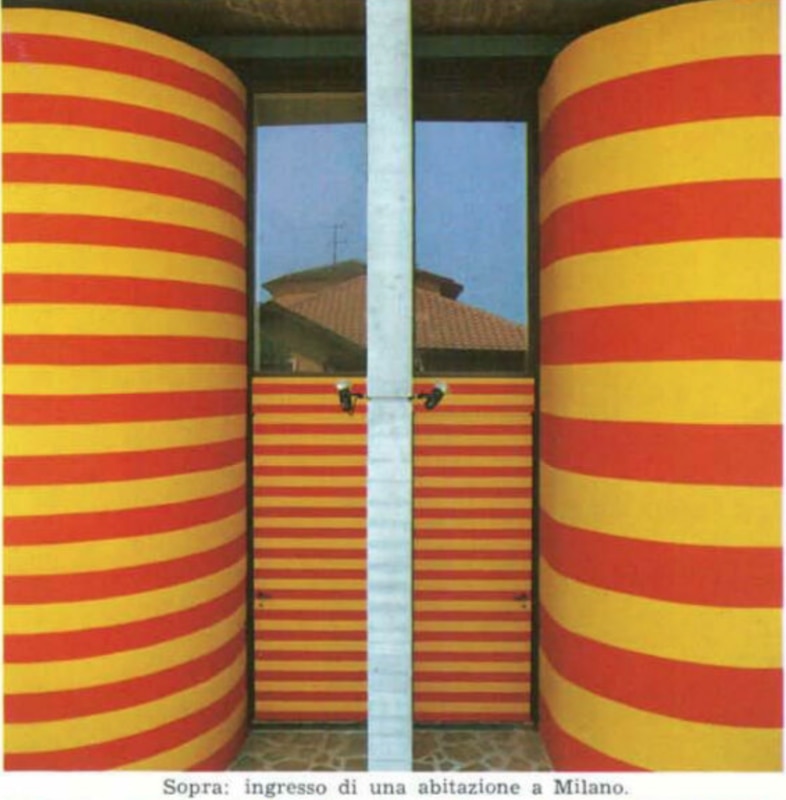

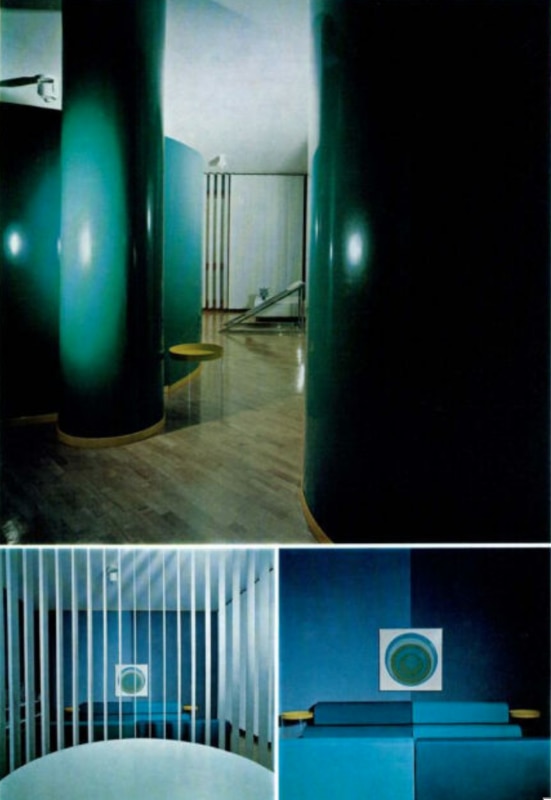

In 1919, when the principles of the Modern Movement were taking shape, a German magazine published an article entitled An Invitation to Coloured Architecture, signed by Gropius, Beherens, Taut and others. This article talked about the problem of colour and how to use it in modern architectural projects. A few years later, in 1928, Piero Bottoni published an article on the same subject in a German magazine entitled Cromatismi architettonici (Chromatism in architecture). After studying these texts, we began to reflect on the use of colour in our practice until it has become our key feature. For us, in fact, colour was an architectural element that modified and defined the space. Alberto Sartoris, in the volume dedicated to our work published in 1980 by Electa, wrote: “the often velvet Salvati and Tresoldi’s harmonies enhance black, red, blue and ochre, yellow, brown and green, brown, white and beige, grey, bistre and purple, both in their horizontal and vertical implications and interweaving. Vivid and bright colours, from zigzagging patterns as Max Bill’s ones, in crossed chains, to black and white zebra stripes, alternating in shapes with screens carved by the sun and the light [...]” (also published in Domus, n. 653, September 1984, p. 30, Ed.).

In your projects of that period there is a certain confluence between architecture and aesthetic trends in the visual arts. Which art were you referring to?

We were not referring to a precise artistic movement but we were immersed in the atmosphere of those years and above all we worked with many of them. In 1968 we organised an exhibition in our studio entitled Achromes where Agostino Bonalumi, Enrico Castellani, Gianni Colombo, Lucio Fontana, Ugo La Pietra, Piero Manzoni, Paolo Scheggi, Tino Stefanoni and Tea Valle, among many others, exhibited. This interest in art and colour had often led us to work with artists. One thinks, for instance, of the beach house whose walls were painted by Giuliano Barbanti, with whom we often work together (and published in Domus, n. 495, February 1971, pp. 25-27, Ed.). The artists did a series of operations within our projects that defined their space.

Do the projects you carried out at that time still exist? What is your relationship with the clients?

Yes, they do. The semi-detached house in Lissone, cover of Electa’s 1980 monograph, is perfectly preserved. That house is one of our most interesting works, the entrance breaks the symmetry of the building through the use of colour and shapes. (Domus, n. 615, March 1981, pp. 42-43). Even that we built in Arenzano in 1978 is still intact. Our clients have always been part of this association, made of architects, artists and gallery owners who, as interdisciplinarity promoters, have always understood and appreciated our work. Once, the daughter of a well-known collector in Milan, having to renovate her house, asked to reproduce the same project as when she was a child, maintaining the colours and patterns of her previous living experience. I think that here the colour takes on an almost nostalgic tone, of home as a container of childhood memories.