This article was originally published in Domus 1047, June 2020.

The first recorded mention of a prefabricated building dates back to the 12th century. It was made by Robert Wace in his description of a castle being assembled from a kit of parts carried on a ship in his epic poem covering the history of the dukes of Normandy, starting with the Viking Rollo of Normandy. It is easy to see how the Viking know-how of wooden shipbuilding was transferred to the making of motte-and-bailey castles that could be erected quickly in enemy territory.

Moving forward several centuries and into the domestic sphere, most houses in Elizabethan London involved prefabricated timber construction. Oak, both hard and weather resistant, was the preferred species and used within 2 years of felling, but it took up to 150 years before it was ready to be used in construction. Off-site prefabrication of structural components proved to be an efficient strategy for denser urban areas. The roof of Westminster Hall with a span of just over 20 metres – built at the end of the 14th century – was prefabricated in Farnham, 67 kilometres south-east of London.

The earliest documented entirely prefabricated structure was Nonsuch House, completed in 1579 and erected in the middle of London Bridge. As a four-storey house, it was originally made in the Netherlands and shipped to London in different sections. It was assembled on the bridge using wooden pegs only. Historians like to link the name Nonsuch as a reference to Henry VIII’s now vanished palace in Surrey, as there was no such palace elsewhere that could equal its magnificence. The name of Nonsuch for the house, however, may well refer to the uniqueness of its construction as it was an unequalled paragon of its kind. It was eventually demolished in 1757 to allow for the widening of the road on the bridge.

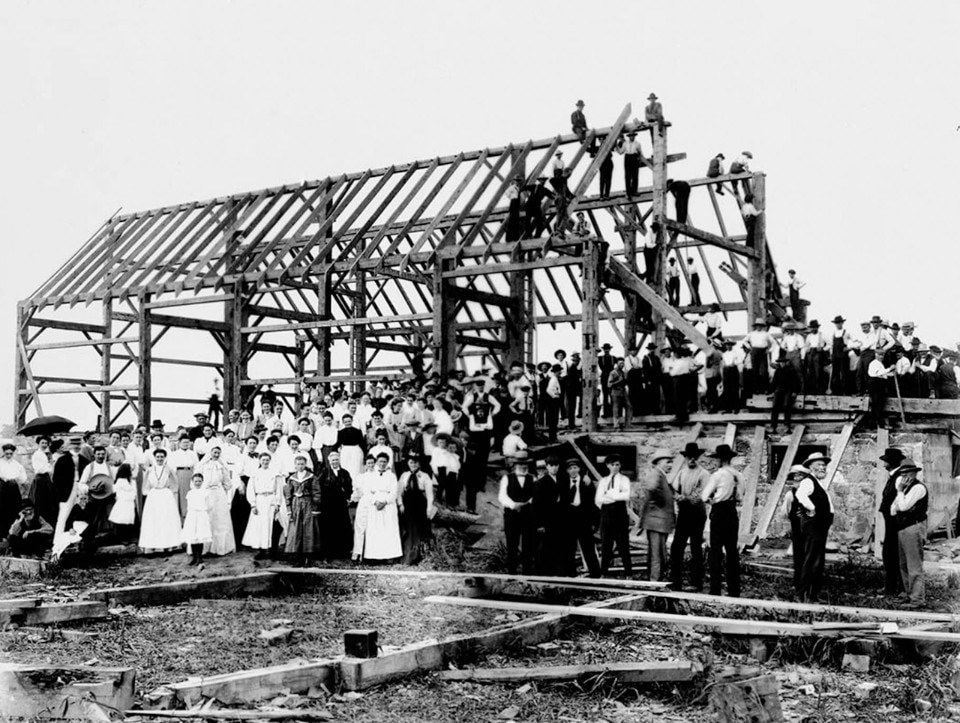

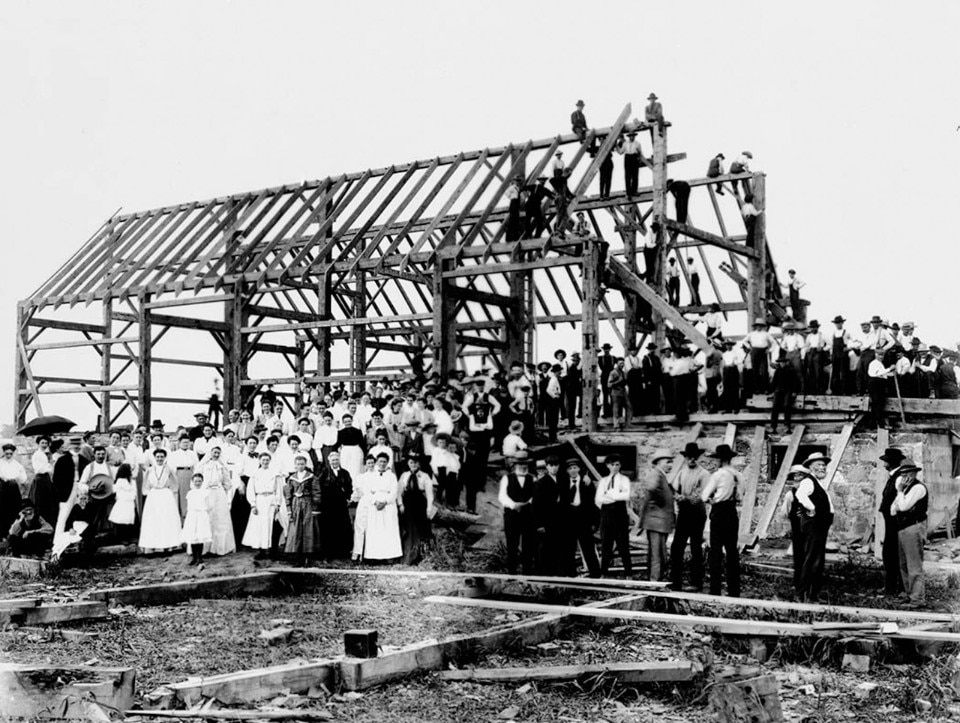

Since the 18th century, the rearing (assembly and lifting) of large wooden barns in North America has been a celebrated occasion, emblematic of a pioneering spirit. In the early 1900s several retailers began to deliver kit houses through mail order, ensnaring prospective buyers with fairy-tale catalogues. Sears, Roebuck and Co. reported selling 70,000 homes over a 34-year period ranging from 2-storey colonial mansions to single-storey bungalows. Many of these houses were assembled by the new owners with the support of friends and neighbours, echoing the traditional barn-raisings of farming communities. However, this idyll was to change dramatically as the avant-garde of the modern era shifted towards concrete – combined with steel – which eventually became the preferred material for construction.

Since the 18th century, the rearing of large wooden barns in North America has been a celebrated occasion

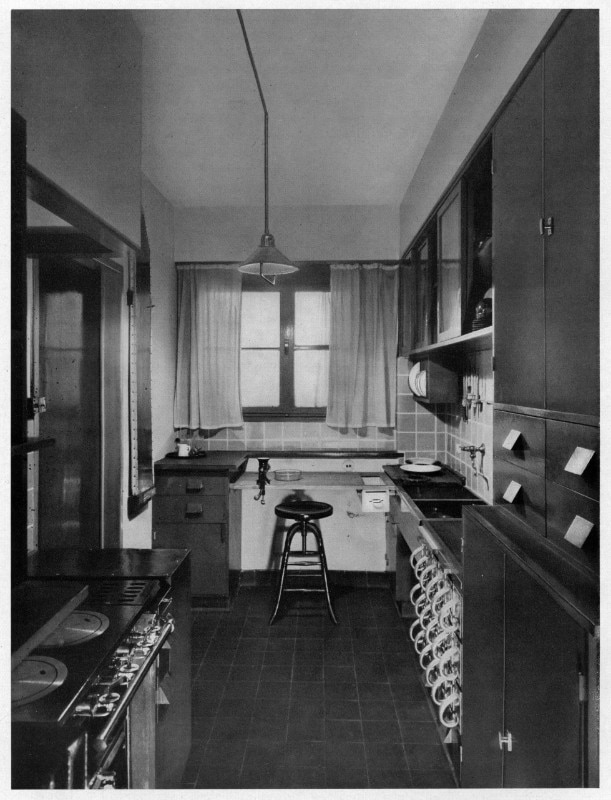

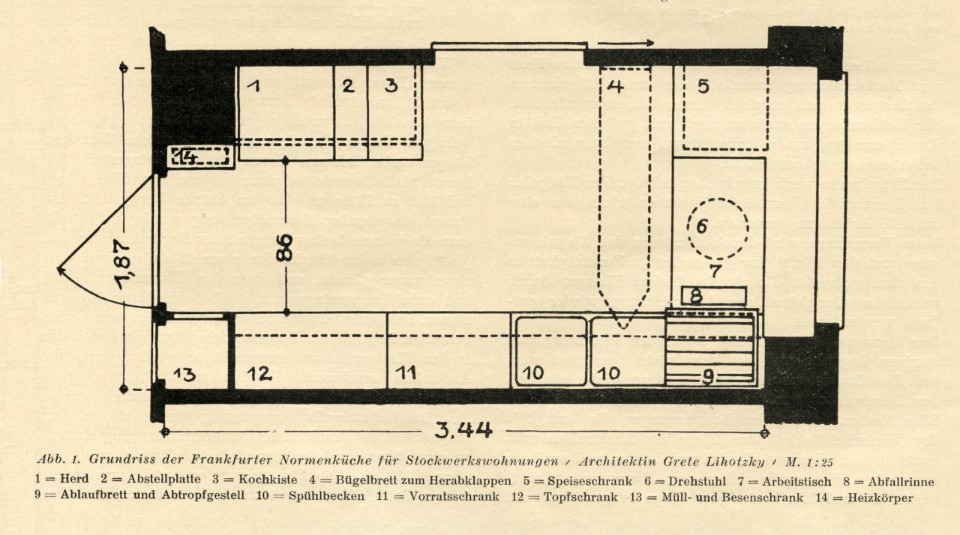

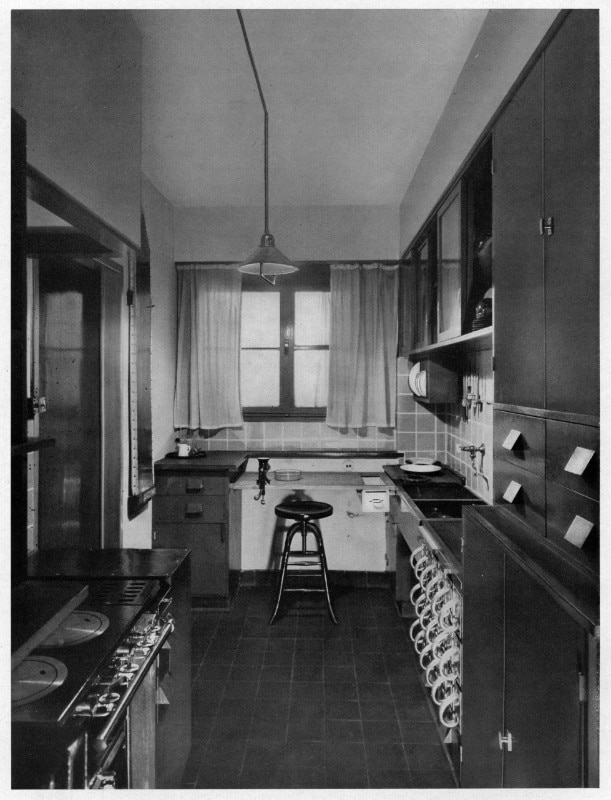

Exposed to the principles of the garden city movement, the German architect Ernst May – who studied under Raymond Unwin in the UK – eventually became city architect and planner for Frankfurt from 1925 to 1930. May experimented with social housing developments fine-tuned with ample community facilities, open-air spaces and general infrastructure. He adopted simplified prefabricated forms, kitted out with the famous Frankfurt kitchen designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Ten thousand units were built, and the concept established fast and efficient design, built at low cost with the parameters of minimum existence for human occupation. Celebrated at the CIAM of 1929, it proved a critical and civic success, and many others developed similar ideas in different countries. Precast concrete panels reinforced with steel offered new opportunities that could not be matched by solid timber construction. Production of these modular, prefabricated homes increased enormously in European countries in response to the common and acute housing shortages following World War II.

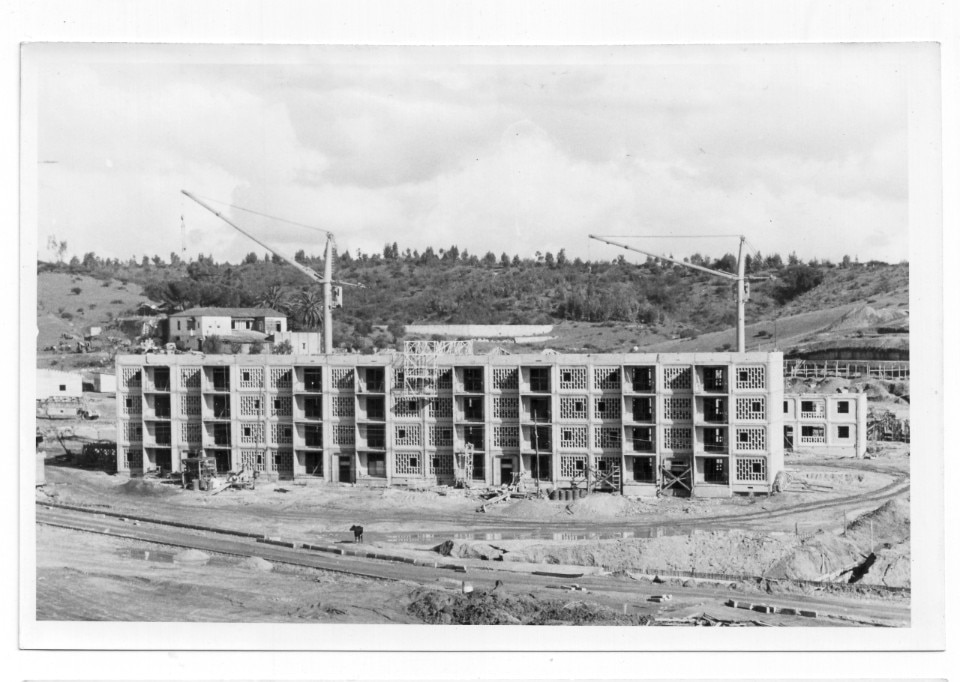

Prefabrication in modular varieties allowing for rapid construction with clean lines was championed by Nikita Khrushchev, who criticised Stalin’s taste for neoclassical pastiche. Countless prisoners from labour camps were released after Stalin’s death in 1953, and Khrushchev provided mass housing for up to 54 million people in less than 10 years. He declared a radical change in planning and construction, adding that prefabrication would be the only method of building in the USSR from that moment on.

The mechanical thinking required for this mass production started in the 1930s with a French pioneer called Raymond Camus. Inspired by the mass-produced Model T car of Henry Ford in the US, Monsieur Camus sought to create an affordable home produced on the conveyor belt, breaking it down into separate components, leaving contractors to simply prepare the site and assemble walls, floors and ceilings – already fitted out with all services – in situ. After World War II, Camus won several contracts in France to provide many thousands of homes, while he kept on tinkering with different models. The success of his product was picked up by Khrushchev’s administration, which acquired one of his patents. Using them politically, Khrushchev eagerly donated prefabricated panels and even entire factories to sympathising nations across the globe.

The concept of the Frankfurt kitchen established fast and efficient design, built at low cost with the parameters of minimum existence for human occupation

Anyone who has travelled around on the island of Cuba will have noticed the omnipresent USSR-donated panel buildings. One can’t help but wonder if these wafer-thin panels are coping in these extreme climatic conditions, taking into account that the same units can be found in Siberia or eastern Germany (where they are commonly known as Plattenbau). The Cubans simply get around it by attempting to hermetically seal off interiors and rely heavily on air conditioning. It is worth noting that today, with the accelerated frequency of hurricanes devastating the island, these prefabricated buildings are proving to be far more resilient than any other construction type on the island.

Over the last 20 years, however, these concrete panel systems have become tainted with negative political associations and deemed physically toxic due to the common ingredients of cement and asbestos. All the more peculiar as contemporaneous early-modern mass-produced (affordable) pieces of furniture have become highly desirable in the meantime.

The nail in the coffin was conjured up by Wolfgang Becker in his film Good Bye Lenin! of 2003, when the mother, looking through the window, witnesses the unfurling of a large Coca-Cola advert on the facade of a Plattenbau. Capitalism may well be seen covering up socialism, but the tide might be turning again. Many Berliners have developed a fondness for the Plattenbau of East Berlin and investors worldwide have started to re-evaluate some of the original ideas at the core of modular prefabrication.

Many of the negative connotations of grey prefab are now circumvented with a new name: DFMA. Design for Manufacture and Assembly now comes with state-of-the-art manufacturing and as you may expect, it has greener credentials, produces less waste, reduces transport, offers greater safety and increased reliability, comes fully tested, offers extensive ranges of interior and exterior options, is made with lower assembly costs – the list goes on. Whether you consider this just a new veil for the same ideas, it is an important territory and should be taken seriously considering a quarter of the world’s population currently lives in prefabricated accommodation. That is 1.9 billion and counting, and the demand has not diminished.

In Sweden, IKEA have entered into a collaboration with construction giant Skandia to produce BoKloks, a modular unit to be part of a village system to which the potential buyers sign up. In the UK, a well-known insurance company has set up a new branch producing modular homes, while a large contracting firm has started a similar initiative, and both aim to accelerate capacity to deal with the increasing shortage of housing in the country.

Interestingly, DFMA is switching back a few gears and returning to timber as its main material. Rather than using trees over 150 years old, it relies on CLT (cross-laminated timber). For every defendant of this material one can find an opponent, and perhaps a proper non-partial evaluation of all materials in the industry and their effect on the environment from a global and local point of view is long overdue. Understandably, undertaking a proper LCA (life-cycle assessment) may pose some problems for serialised prefabricated units as their dispersal after production cannot be predicted.

The role of architects on the other hand equally needs looking at afresh. Several practices like Bauart Architects in Switzerland or Studio Bark in the UK have become positively involved in this field by looking at engineered systems, some of which to be assembled by the end users themselves. In Estonia, a practice called Kodasema OÜ Architects markets units that can be driven to site in their entirety. All these design initiatives prove that the “prefab home” is far from extinction but somehow reverting back to the self-assembly mail-order kits of the early 20th century as they are only accessible to the (relatively) well-off. A greater challenge would be to consider, or reconsider, how we might expand a minimal system with maximum qualities for the communities in most urgent need around the globe. .