This article was originally published on Domus 1043, February 2020

More than a century after Adolf Loos wrote Ornament and Crime (1913), the discussion on ornament is still far from settled. The debate – is ornament unavoidable or is it vain decoration? – has driven key changes of direction throughout the history of architecture. Ornament is also the barometer of prevailing theoretical positions. By looking at the way ornament coincides, or coexists, with architecture we can decipher historical changes, sudden accelerations or nostalgic reprises. Most importantly, we can arrive at an understanding of how ornament might be used today.

Contrary to what for a long time has been common opinion, the evolution of the ornament-structure binary is the story of progressive separation. This process occurs as a steady distillation rather than basic removal. Looking at Roman architecture, we can find occasions in which ornament is not perceived as a pure embellishment but rather is conceived as armour or the correct vestments required to officiate at a ceremony. That is the case of the Tomb of the Baker near the Porta Maggiore in Rome which, for example, can be considered a unique whole.

It was only in the 15th century that the first semantic dissociation happened. Leon Battista Alberti was the first to recognise ornament as an entity, separable from structure. In questioning its existence he thus opened a crack which was bound to expand. Alberti lived in mercantile, proto-capitalist Florence, which seems the natural context in which to start separating what is useful (or profitable) from what is not. Even if he did not take full advantage of the consequences of his discovery, Alberti unwittingly crossed a line of no return which would only acquire meaning in the following centuries.

In every evolution in thinking about ornament comes a rethinking of the past. In the second half of the 19th century, Gottfried Semper asserted that the origin of architecture was concurrent with textiles. ‘‘The beginning of building,” he declared, “coincides with the beginning of textiles.” His theory marks another huge step in the narration of separation.

As stated by Semper, structure belongs to tectonics while cladding originates from the very structure of fabric, the alternation of warp and weft. Like a dress, cladding has the right to express its texture. Like cloth, it can change according to the needs of specific occasions. Cladding, according to Semper’s theory, possesses an expressive nature which empowers the social role of the building.

Even though architects and theoreticians fought to preserve the integrity of ornament and architecture, reality has followed another course. New building technologies have historically forced a renewed and stronger separation between structure and skin. The entirety of Louis Sullivan’s oeuvre in Chicago is perhaps the clearest example of this running schism.

The impressive photographs of the developing city in the late 19th and early t20th centuries depict skyscrapers under construction before they are dressed in ceramic curtain walls, like scaffolding covered by a soft cloth. If a ceramic facade must be deployed to protect steel structures from fire, the dissociation between structure and ornament is inevitable.

Gottfried Semper’s position was that both the wall and the tent are architectural skins and thus walls can be considered the descendant of tents. As thick and structural as stone, bricks or mass concrete, or as thin as a cladding layer, a textile dress or a coat of paint, the skin of a building is what separates interior spaces from the outer world. Walls have often been the expression of the tectonics of a building. The way tents are sewn, the way bricks or stone blocks are assembled and the way concrete is moulded make it possible for us to understand the architectural and structural intentions under the surface.

Loos, ultimately, was not against ornament. It was just that for him, inventing a new ornament was impossible as the present had overcome the need for decoration

Indeed, what is currently occurring in contemporary architecture – some examples of which illustrate this essay – is a deepened understanding of the significance of ornament, and not just at the obvious level where it intersects with structure. Consider patterns, which are generally dismissed as decoration. Despite their apparent innocence, patterns hide organisational structures reflecting the time and society that generated them.

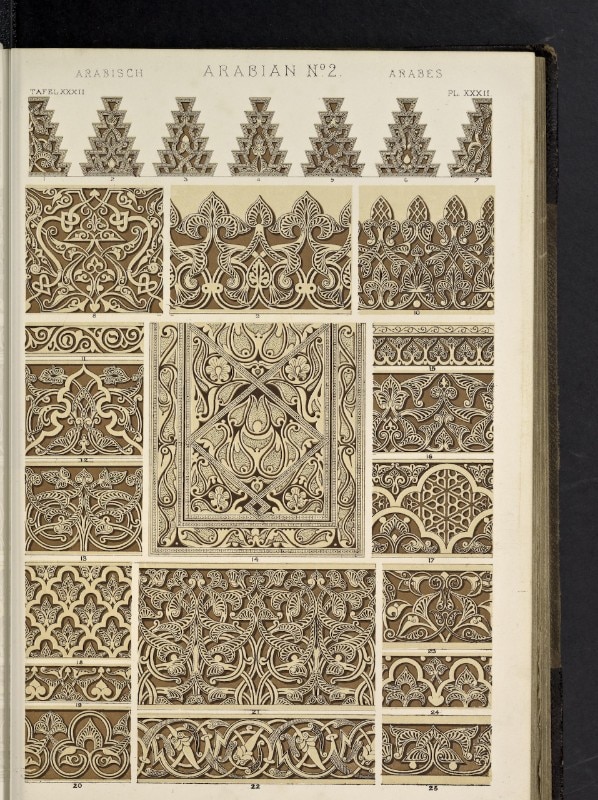

Take Owen Jones’s masterpiece The Grammar of Ornament (1856), which can be read in many ways. On one hand, the book represents the attempt of a British intellectual to document the use of ornament. Jones’s broad selection could rely on the vast network of the British Empire and contains a global collection of patterns and rules for their application. Yet there is another conflict taking place. Jones condemned the role of industrialisation while implicitly encouraging the development of the mechanical reproduction of ornamented patterns. The ambiguity of his position was brought to its extreme by the active role he had in designing the interior decor of the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition in 1851.

Adolf Loos’s take is apparently much clearer as he firmly opposed the reproduction of classical ornament in an era when industrial production progressively substituted craft. His condemnation resonates in the title of his most famous essay. Yet in his built work, Loos made use of classical ornament – as with the Tuscan columns for the bank building on Michaelerplatz in Vienna – which appears to contradict his position. But it actually reinforces it. Loos, ultimately, was not against ornament. It was just that for him, inventing a new ornament was impossible as the present had overcome the need for decoration.

Loos opened up an argument which was fully embraced by the Modernists. In the most simplistic interpretation, modernists are totally against ornament in architectural production. Once more, this statement needs deeper analysis. Certainly, while apparently avoiding it, the modernists actually gave ornament a new form. Le Corbusier’s persistent use of colour was an exercise in providing the thinnest possible layer of cladding.

Buildings like the Palace of Assembly in Chandigarh (1962) as well as the Unité d’Habitation (1952) in Marseille show how coloured surfaces can in unison construct particular kinds of space or give space particular qualities. The other crucial aspect characterising Le Corbusier’s work is the way in which materials are granted the capacity to be ornaments themselves. Following Auguste Perret’s lesson, Le Corbusier enhanced the sculptural properties of in-situ poured concrete to determine the quality of large bare surfaces at the Unité d’Habitation.

Nor was he alone in doing this. Mies van der Rohe used very specific materials because of their implicit expressive nature. In the Barcelona Pavilion (1929), Roman travertine, green Alpine marble, green marble from Greece and golden onyx from the Atlas Mountains were displayed bare, like textile curtains defining spaces.

In the 1970s, while attacking modernism, Venturi and Scott Brown, in their own way, defined the postmodern ornamental agenda: “When modern architects righteously abandoned ornament on buildings, they unconsciously designed buildings that were ornament.” This happens because the negation of ornament is, according to Venturi and Scott Brown, still a communication tool. In the decorated sheds, the ornamental apparatus is a superimposed layer – the main architectural means of communication.

Yet architecture in the past was always characterised by a certain economy of ornament. Its presence, even if massive in scale, has always been concentrated in a few key elements in a building: the profile of the mouldings, for example. The risk of the current banalisation of ornament is a drastic loss of complexity and the transformation of it into mere decoration

The contemporary debate about ornament is as revealing as it ever was. If ornament has become associated with parametric architecture and, generally, with the figurative treatment of evenly decorated building envelopes, then there is another group of architects pushing against this. Firstly, they say, this interpretation hides the assumption that architects nowadays should be busy designing perfume boxes with undefined interiors.

Secondly, it presumes that contemporary ornament is a single overarching gesture which is supposed to determine the entire building envelope. Yet architecture in the past was always characterised by a certain economy of ornament. Its presence, even if massive in scale, has always been concentrated in a few key elements in a building: the profile of the mouldings, for example. The risk of the current banalisation of ornament is a drastic loss of complexity and the transformation of it into mere decoration.

When we were asked to contribute to an exhibition on the subject at the Trienal de Lisboa, we wanted to bear witness to the fresh, self-confident and joyful return of ornament since the early 2000s. Today, it seems natural to carefully consider the junctions among elements; to question the nature of cladding as a project rather than as a consequence; to design expressive facades with images and typography; and to dress surfaces with patterns, motifs, textures, materials and colours.

As architects, we sometimes need to concentrate our efforts on the ornamental apparatus in order to maximise results. Whether this process is conscious or unconscious, or simply a reaction to a lack of means, it seems necessary to redefine the current threshold between ornament and decoration; to rethink what we can allow ourselves in our daily practice.

Ambra Fabi and Giovanni Piovene are co-founders of Studio Piovenefabi based in Milan and Brussels. In 2019 the studio curated the exhibition “What Is Ornament?” as part of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale.