When we think of the architectural heritage of a region such as Sicily, the first examples that come to mind are undoubtedly ancient: the Cathedral of Syracuse and the Temple of Selinunte, the Baroque route in the Noto Valley and the Arab-Norman route in Palermo. The grandeur of these examples overshadows a period, the modern and contemporary, that continues to offer us extraordinary examples of architectural and engineering works. This selection of modern architecture therefore has a somewhat broader meaning: to avoid a folkloristic and stereotypical vision of places, whose identity is always richer and more layered than that sold by big brands (yes, I am talking about Dolce and Gabbana) and tour operators.

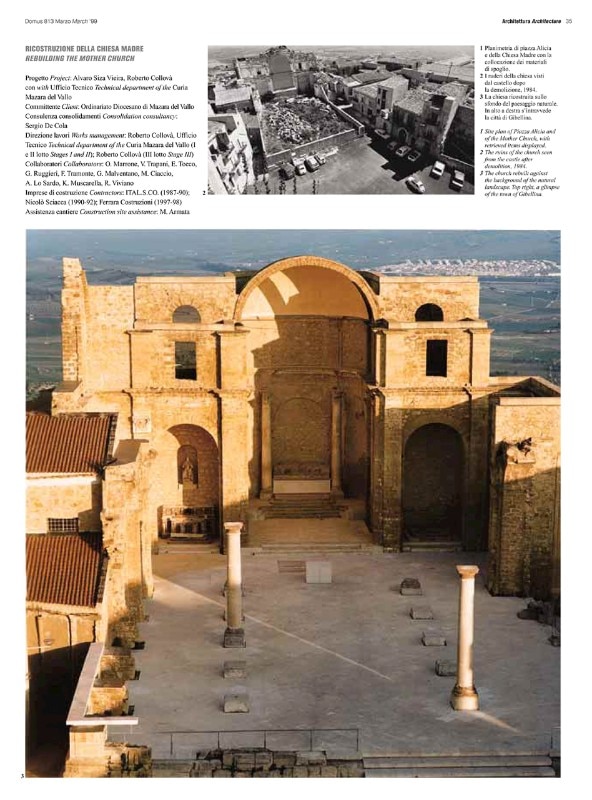

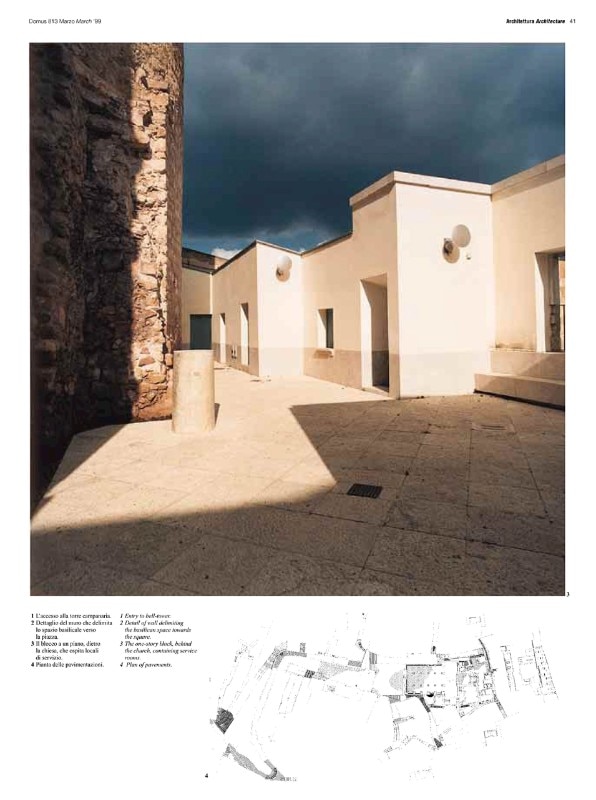

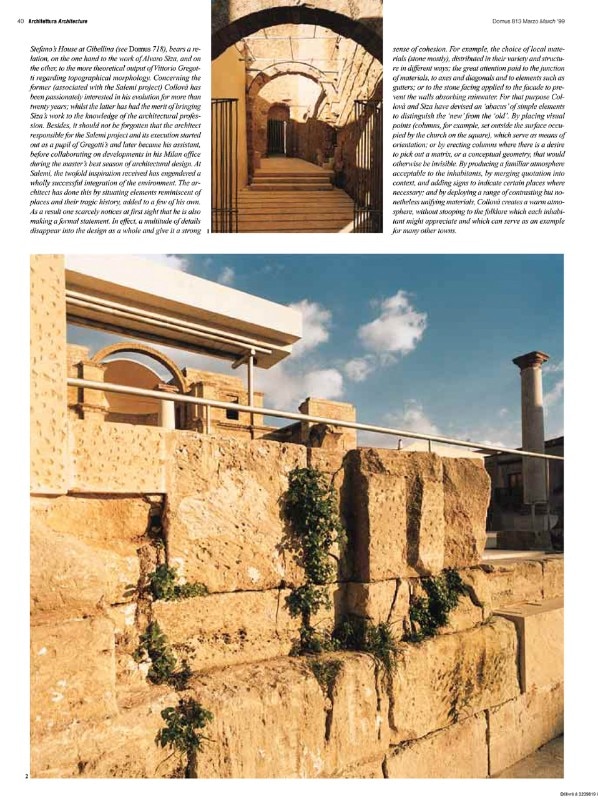

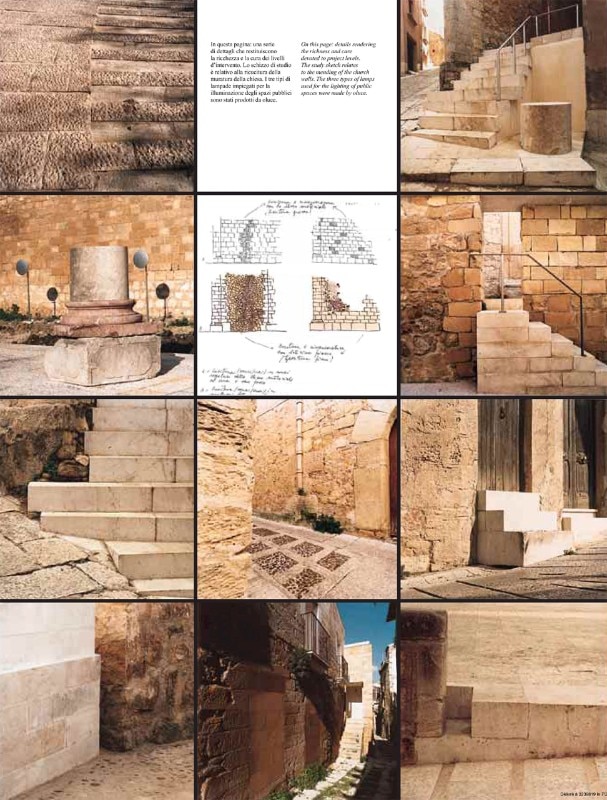

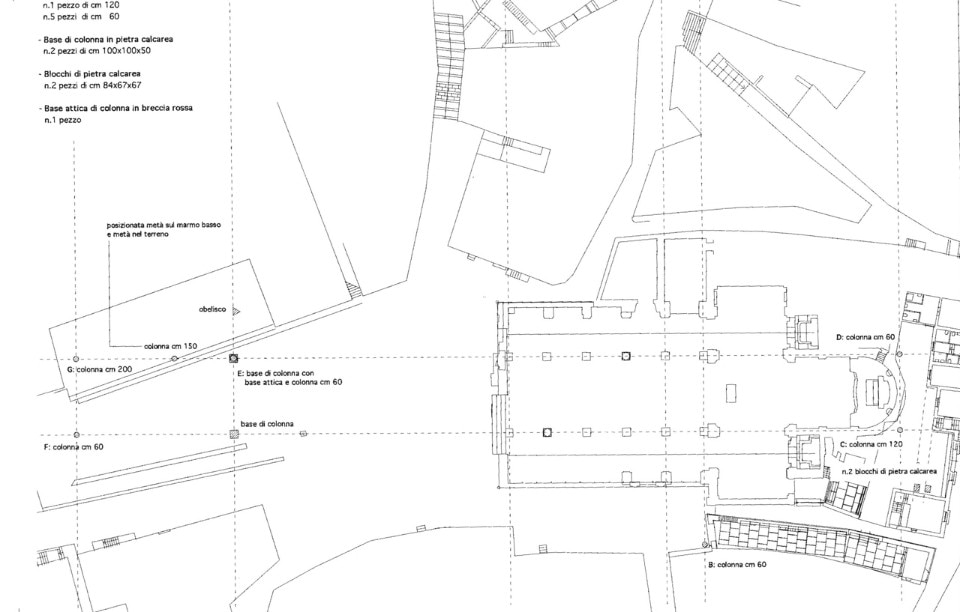

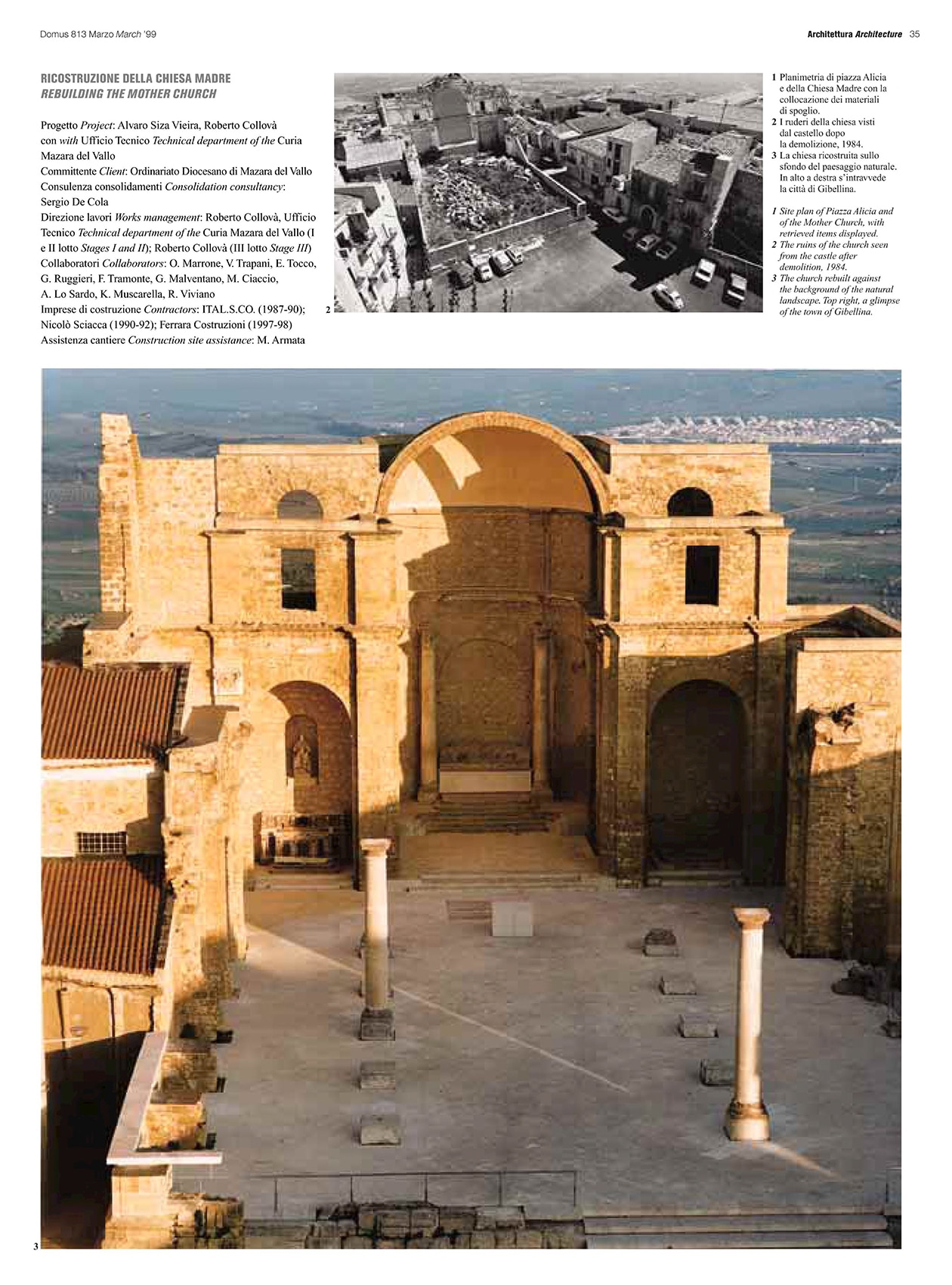

Álvaro Siza and Roberto Collovà, Alicia Square and reconstruction of the Mother Church of Salemi

We can hardly find better words than those of Francois Burkhardt, director of Domus from 1996 to 2000, to comment on the ideas of Siza and Collovà, who redesigned the streets, the square and the Mother Church in Salemi with a series of careful and resolute micro-interventions: “After the 1968 earthquake in Sicily, numerous reconstruction programmes were drawn up. Seldom, though, has the attempt to reorganize the public space of a small town, with particular regard to local atmosphere, been so convincing as in this case. To achieve that goal it is necessary to grasp the spirit of the ancient place, but also to have the courage to describe it anew.”

Giancarlo De Carlo, recovery of the Benedictine Monastery

The restoration of the Benedictine Monastery lasted 25 years. Architect Giancarlo De Carlo was invited by the University of Catania to the Benedictine Monastery in 1980, and the last parts of the project were completed in the first half of the 2000s. The intervention introduces strongly contemporary elements, which are layered with ancient ones, creating a dialogue between present and past and offering new uses. De Carlo’s solutions aim at a reuse in which even the superfetations acquire the value of a “narrative text”: they highlight and narrate the stratifications, the choices made, even if not shared, in the past.

Riccardo Morandi, Costanzo Bridge

Between Modica and Ragusa we find one of engineer Riccardo Morandi’s best-known works: the ‘Costanzo Bridge’ is an impressive 168-metre-high infrastructure. When it was inaugurated, it was the highest bridge in Italy, and still remains the highest in Sicily. A unique feature of the bridge is the use of steel for the transverse spans (an unusual solution for Morandi), while the giant pillars are made of reinforced concrete. Nearly a kilometre long, the longest span is about 180m. In Sicily we count more than a dozen public works built by Morandi, including bridges, viaducts and airport areas.

Italo Lanfredini, Ariadne’s Labyrinth

Near the small village of Castel di Lucio, on top of a hill in the Nebrodi Park, there is an immense labyrinth to walk through: it is the Ariadne’s Labyrinth, one of the 11 works in the Fiumara d’Arte project. More than architecture, it is an artistic work that originates from the myth of Theseus and Ariadne. It is a physical spiral path, but not only that, and crossing it also means taking an inner journey.

On the park’s official website, a text explains the meaning of the work, which “is connected to the past, to classical culture, to birth, to the first teachings of life. Through a natural gateway, one enters and leaves the labyrinth, just as man has entered and left it over time. He who enters the labyrinth asks questions about his own existence, in a place and in an a-temporal dimension, in which it is impossible to question oneself.” At the centre of the labyrinth is an olive tree, a Greek symbol of wisdom and knowledge, which is the ultimate goal of the proposed inner journey.

Alberto Burri, The Great Crack

In 1968, a violent earthquake completely destroyed the small medieval village of Gibellina, a few kilometres from Palermo. The urban centre was completely rebuilt some 20 km from the original site. Architects and artists of international calibre contributed to the reconstruction. With his work, Alberto Burri moves away from the new context to embrace the ruins of Gibellina Vecchia. The rubble and remains of the destroyed city are transformed into an urban-scale cretin in which concrete islands reconstruct the original blocks, becoming in turn a reminder of it.

Farm Cultural Park

What has been enlivening the alleys of Favara’s historic centre since 2010 is much more than just an urban regeneration project. Farm Cultural Park has succeeded in creating around itself an international community of artists and designers who, together with the town’s inhabitants, develop initiatives of various kinds – from the SOU school of architecture for children to the biennial Countless Cities exhibition. Favara has quickly become an incubator of innovation and one of Sicily's new centres of the contemporaneity.

Carlo Scarpa, installation at Palazzo Abatellis

Once again, we draw from the Domus Archive to recount one of Palermo’s most beautiful palaces. “Called to prepare the rooms of the new Gallery of Sicily in the Abatellis Palace, Scarpa found amongst the powerful ashlars, the ideal archetypes of his material voluptuousness, of his sensitive taste for form and making geometrical; he found the fabulous space of his imaginary figure, reconstructed the charm that these places recall and on the impressum invented his dialettic itinerary.” (Domus 708, September 1989)

Lorenzo Reina, Teatro Andromeda

“Teatro Andromeda was born from the dream of a shepherd who did not want to be a shepherd, but a sculptor, in the second half of the 1980s. And only as a sculptor could he conceive and realise this theatre,” says Lorenzo Reina, author of the Andromeda Theatre. This exceptional work is set among the peaks of the Sicani Mountains, in the territory of Santo Stefano Quisquina (Agrigento). It is the highest theatre in the world, a place where time seems to stand still and the work of man enters into harmony with the raw natural landscape.

Michel Andrault e Pierre Parat, Basilica Santuario Madonna delle Lacrime

Designed by French architects Michel Andrault and Pierre Parat in 1957 – following an international competition – and only completed in 1994 due to various delays, the Basilica Santuario Madonna delle Lacrime in Syracuse is a unique work of its kind. Among the reasons for its late completion is undoubtedly its brutalist language, which triggered much controversy from the very beginning on the part of the citizens who considered and still consider the work a “concrete monster”. The Sanctuary is a bold construction that can be likened to a hyperbolic paraboloid, at the base of which is the crypt that measures 71.4 metres in diameter and 74.3 metres in height from ground level. The structural works are by engineer Riccardo Morandi.

Pier Luigi Nervi, Hangar in Pantelleria

Pier Luigi Nervi’s most important public works in Sicily are the hangars built in Marsala and Pantelleria for the Royal Navy. In these infrastructures, Nervi applied innovative solutions in the design of the large roof vaults, characterised by crossed concrete arches. His experiments made it possible to reduce the number of support points, considerably increasing the internal spans for aircraft. The military building is now used by the Municipality of Pantelleria for exhibitions and various events, and can therefore be visited by the public.