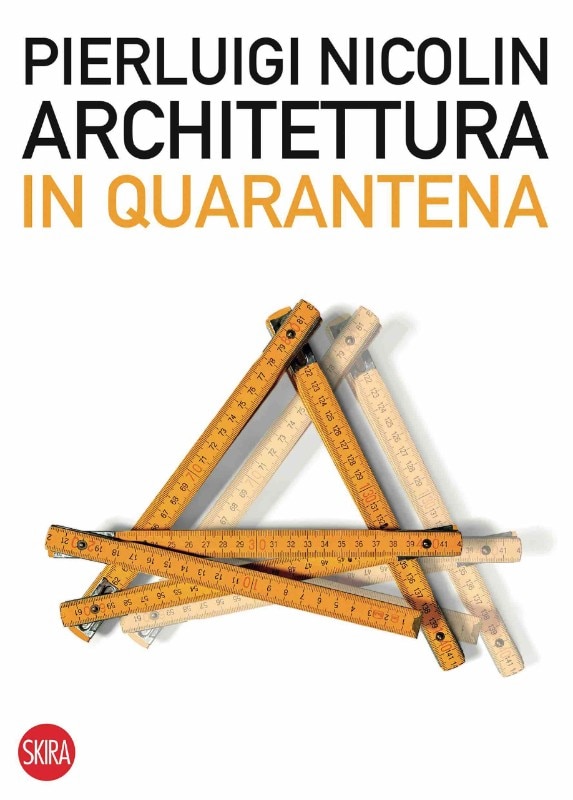

Pierluigi Nicolin, architect and Lotus magazine’s director since 1978, told me about the reflections he collected in a small diary he started writing during the lockdown and finished at the end of July. The pandemic brought to light some new and unforeseen facts that led us to reflect on the future of architecture. Our conversation took place a few days before the government ordered a new lockdown to prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Your diary begins with the image of Pope Francis’s solitary prayer service on the sagrato of St. Peter’s Basilica on 27 March 2020. At that moment, the square became a counter-place, a “heterotopic” space.

The resounding event in St. Peter’s Square forced us to reconsider our places of reference, which were affected by an inversion of the usual relationships, the so-called “heterotopia”. This term has always had a medical meaning, indicating the displacement of an organ from its normal position. But then, Michael Foucault elaborated the notion in more philosophical terms – now heterotopia defines those spaces that are connected to all the other places, but in such a way as to suspend, neutralize, invert the set of relationships that they reflect. The notion of heterotopia has imposed itself in a totally unforeseen way and as a general condition during the COVID pandemic. We are currently experiencing the greatest heterotopia of all time.

The notion of heterotopia has imposed itself in a totally unforeseen way and as a general condition during the COVID pandemic. We are currently experiencing the greatest heterotopia of all time

In this situation of forced imprisonment, other spaces besides the square have taken on different meanings, such as the balconies, which could be considered as “resistance forts”.

Even empty streets have become “other” places if compared to their usual role – they no longer serve as streets. And the reappropriation of forgotten spaces, such as balconies, which have become theatres of domestic life, is an interesting fact because it also shows the rediscovery of a sense of community, and the desire to overcome the limits of space.

Have these theatres of domestic life, which “emanate a burst of vitality and hints of understanding”, proven to us that the virtual world is perhaps not enough and that there’s still a need to “manifest” ourselves?

Certainly, that’s exactly what it is. The observation I could make now, in hindsight, is that an event brings many things to light – in this case, it has revealed the precariousness of many public spaces as well as the use of the balcony as a place to exorcise fear.

We have also witnessed the transformation of other important places – especially the school, as an institution and also as a “building”.

In my book, I talk about the school because it induces a sense of nostalgia for physicality. At a time when we feel like we can do everything remotely, thinking about the school makes us feel a great nostalgia for the human contact, the presence, the body. When talking about this, I quoted the beautiful story Azimov wrote in 1954 – a school that is made up of all the voices in the courtyard, of sitting together, of going home together after class, of talking about the homework. A community of research guided by real teachers, and where the teachers are real people.

You also talk about the school not only as an institution but as a “mnemonic tool”.

I talk about physicality because the physical aspect is a memory tool, and it is a very important aspect – in fact, the art of memory is linked to the fact of associating an image to something. To remember that something, I need to remember where it is. And this is what the school is for. Let me give you another example. The library we might have in our home can have a great value – that of reminding us of a lot of stuff through its physicality.

Even the workspaces suddenly have had to completely rely on technology and information technology.

Yes, but that mustn’t always be like this! I feel a little skeptical about seeing distance as a starting point. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, sociologist Melvin Webber’s thesis “Community without propinquity” was very popular. Webber imagined the cities of the future – places where the people would establish social ties and relationships in a “non-local urban territory” by relying on telecommunications. This idea is coming back in vogue, and I still feel skeptical about it. I am an architect, so I am used to working remotely. I can make a sketch, and I send it out for something that will be built, for example, 300 kilometers from where I am. We are used to working remotely thanks to technology, but we also know its limits.

Your reflections also focus on other areas concerning the concept of distance.

Building life around the concept of social distancing introduces problematic issues: if everything happens “at a distance”, then even the purchases will be made at a distance – only e-commerce will survive and all shops will close down. Designing without really thinking about it, and only after things happen, to me is an awful system. It happened in the United States with the malls, a world that is now facing a great crisis and that has however destroyed what used to be the main shopping streets – all shops in American towns have closed down because everyone was buying in the huge shopping malls next to the highways. We have seen and experienced what solutions of this kind have brought, and it is not something we should want. So, we must hope that this social distancing concept will only occupy a marginal part of our lives, and will not destroy everything else.

So, we must hope that this social distancing concept will only occupy a marginal part of our lives, and will not destroy everything else

This forced imprisonment has produced “intolerable claustrophobias”. Philosophers, writers, and creatives have shown the difficulty of dealing with the situation in a calm manner. Renzo Piano, for example, suffers at the thought of his works being abandoned, and wonders how it is possible to create without drawing inspiration from reality and contact with people.

Coronavirus is a serious matter, but, as Camus wrote in The Plague, you have to resist, accept the scandal, walk in darkness and try to do good. We have to live with this thing, which we do not understand. Implicitly, however, I gave a solution to Piano, by stating that people are much more than our architectural space. I talk about this in the chapter dedicated to proxemics.

Coronavirus is a serious matter, but, as Camus wrote in The Plague, you have to resist, accept the scandal, walk in darkness and try to do good

You introduce the reflections on proxemics with another iconographic reference: Canaletto's Capriccio, which is currently displayed at the National Gallery of Parma.

Proxemics is a subject that has always fascinated me. The body is not an object that inhabits (or not) architecture. Our physicality, animality, or humanity – let's call it that – is made to build complex syntactical relationships. With the environment comes a body language, and to demonstrate this I enjoyed analyzing Canaletto’s Capriccio, in which I attribute the value of identity to the people in the painting and not to architecture. People inhabit the space, and help us understand that we are in Venice – it is not architecture that defines the place, but people. People are more than just the inhabitants of architecture; they are often the guarantee of the authenticity of the place. I wanted to say this, and I don’t care if it’s right or wrong.

People are more than just the inhabitants of architecture; they are often the guarantee of the authenticity of the place

You suggest not to design architecture by only focusing on the social distancing aspect, because it is unnatural behavior.

Socially distanced architecture can lead to dangerous results. We are not ready for it; we still have to internalize what has happened to us before making such suggestions. Since we are distressed, we rush to schematize and deconstruct the city, but we must keep in mind that social distancing is unnatural, it mustn’t become our normality. I find it aggressive and vain to use social distancing as a starting point to design architecture. What can it mean? You can just go to the cinema to realize that. How can you enjoy an experience in those conditions? Social distancing, which has a military character, is necessary now because otherwise we get infected, so it must be respected. But it is very different from turning an exception into a rule. You have to be very careful, because a lot has been said and talked about rebuilding the city, the house and the rooms in this period, and I must say that a lot of it was nonsense.

Since we are distressed, we rush to schematize and deconstruct the city, but we must keep in mind that social distancing is unnatural, it mustn’t become our normality

So, what can architecture do after a situation that you imagined could take the form of a “gust of wind”?

We have to internalize it; we are not ready for an immediate response. I am not ready either. We need to slow down. Architects believe they have universal medicine, the panacea. I have preferred to be more “modest”. When I was working on an architecture magazine, I asked myself, why not develop the good things that were proposed in recent years but were never implemented? Let me give you an example: in the City life district in Milan, the big “crooked” tower is now empty. Eight hundred people used to work there, now there are only twenty of them. The others work from home. But nobody has thought about what it really means: remote working works if I can control it in detail, and how this can be done. Then there is not only the desolation of an empty tower, which hopefully will come to an end, but there is also the danger that remote working will become a matter of totalitarian control.

I agree with Professor Shoshana Zuboff’s when she talks about “surveillance capitalism”. I agree with the idea of cooling the enthusiasm for remote working. I see it even now at university. I deal with a lot of people who teach, and I cannot say that they feel enthusiastic about this way of working.

c’è anche il pericolo che il lavoro a distanza diventi un fatto di controllo totalitario

Do you hope that architecture will not be used as a pretext for mere formal exercises, but rather to encourage people to work to make ordinary things interesting?

I am sure of it. Future design will have to focus on the limits of the home and think about creating meeting places, which are certainly unthinkable at the moment, but which we will return to populate. We have a lot of things to do, there is no need to sketch an improvised utopia!

Future design will have to focus on the limits of the home and think about creating meeting places, which are certainly unthinkable at the moment, but which we will return to populate. We have a lot of things to do, there is no need to sketch an improvised utopia!

You propose strategies or design solutions, including the concept of “grafting”.

The point is not to do anything without really thinking it through. Grafting means that you are dealing with something that you must see as a starting point – you have to work on a plant that you already have and that you cannot ignore. We have to cultivate what is close to us.

Architecture must develop the concept of lightness and flexibility, which can help respond to the change of use of the space. It is not a technological problem, but an anthropological one.

Other possible solutions, according to you, might be intervening on mobility and reorganizing travel times.

These are the most important things from which to start. Right now, we have a very mediocre model if I think of the bike lanes built in a totally reckless way. Sociologist Richard Sennett is right when he says that “a city does not exist unless you cross it”. I am completely fascinated by the concept of crossability. Interventions on mobility would have a regenerative function for the city. Also, when it comes to travel times, unfortunately, it is spoken of miserably, like when they suggest workers should avoid rush hours: this is superficial functionalism, and it is linked to an urgency. Instead, I would like to deal with this issue by having a long-term vision.

Despite the difficulties, you recognize that Italians have a great ability to "bounce back".

Italians are resilient. Resilience comes from the Latin verb resilìre, i.e. to bounce. In the past, it meant that when one falls into the sea from a boat, they’re able to immediately get back up: resilience means getting back up. Did we fall? We will get back up.

In your book, there are numerous literary references to dystopian scenarios, such as the famous passage in The Betrothed, in which Renzo returns to his native country, which is devastated by war and the plague.

I have collected some examples; literature offers numerous examples of dystopian narratives, of deserted countries, destroyed and abandoned after the epidemics. We also got very close to the scenario of dystopian novels, such as Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 and Orwell’s 1984.

There is also another way of reacting to a crisis – isolation, insularism.

As Foucault said, utopias comfort. After the great plague epidemics, artists created many works of art that recounted escape as a response to the crisis, such as the Decameron. Even now, we hear these proposals to move to the countryside, and the theme of the refuge returns. The noblest and most painful missing utopia that I take as an example, is the one proposed by Jonathan Franzen in his beautiful book The Corrections. Franzen criticizes contemporary society and comes to the conclusion that everyone might as well take responsibility for doing the things they’re doing well and for caring for the environment in which they live. Franzen follows the position of Voltaire when Candide says that “we must cultivate our garden”. This attitude does not solve problems. If you want to preserve your garden, if you give up changing the situation, you go back to being a localist, you are bound to erect other barriers.

It is better not to bet too much on these little utopias, like Franzen’s, in an era of pandemics and climate disasters, where it is difficult to imagine that only a few will be saved.

As Foucault said, utopias comfort. After the great plague epidemics, artists created many works of art that recounted escape as a response to the crisis, such as the Decameron. Even now, we hear these proposals to move to the countryside, and the theme of the refuge returns

In your book, you feel the lack of a design motivation or the call for a moral renaissance. Do you still think so today?

I think we are in a slightly “deformed” phase; we still need to clarify our ideas. For now, we are over-focused on our free time, but nobody talks about how we should work, or whether we should have children or not; instead, there is this emphasis on dancing, football, music, and museums. It seems like we all go to museums, but the issues are deeper.

I don’t have a better idea than to roll up our sleeves and work on the city that is already there, which is not bad at all, and try to make sure that we don’t immediately turn the architectural project into a business. Let’s not start from scratch, and let’s not concentrate only on museums and La Scala concerts: our city is our way of life, that’s what I think.

our city is our way of life, that’s what I think

In 2021, the theme of the Architecture Biennale will be “How will we live together?”. What do you expect?

It’s not a bad starting point if it doesn’t become sociologism. The titles of the Biennials are always a bit pretentious; I’d prefer the title to be “how to get back in touch”. I would like us to reflect on how to re-establish human contact.

I would like us to reflect on how to re-establish human contact

These days, do you feel more of an attitude of escape or resilience?

This is a bad time, people are discouraged. I think that the noblest thing to do is trying not to be overwhelmed. We imagined this pandemic to be a different, transient, episodic scenario. Will it be like this – a parenthesis in time? I don't know. It might be, in certain ways… but I don’t know how long a parenthesis it will be. Apparently, it’s not yet time for great ideas.

I was surprised by the poetic implications of your consideration, quoting the words of Lucio Dalla, which were words full of hope...

Dalla was a genius! Today we are experiencing a sad situation, from which we hope to get out soon. It’s something similar to the atmosphere during the Years of Lead described by Lucio Dalla: “We don’t go out much in the evening, even when it’s a holiday”. We’ll see about that.

Opening Image: Illustration By Paolo Metaldi, Eterotopia, 2020.

© Courtesy Paolo Metaldi

A house turns its back on the road to open up to the landscape

The single-family house project designed by Elena Gianesini engages in a dialogue with the Vicenza landscape, combining tranquility and contemporary style through essential geometries and the Mazzonetto metal roofing.