Our visit to “The Poetics of Reason”, the fifth edition of the Lisbon Triennale of Architecture curated by Éric Lapierre (which we introduced here), begins at the Central Tejo of the MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, on the banks of the Tagus river in Belém. The huge red brick building, with its characteristic thin vertical windows, is a former power station. It was converted into a museum in the 1990s, and its expansion was carried out by Amanda Levete Architects in 2016.

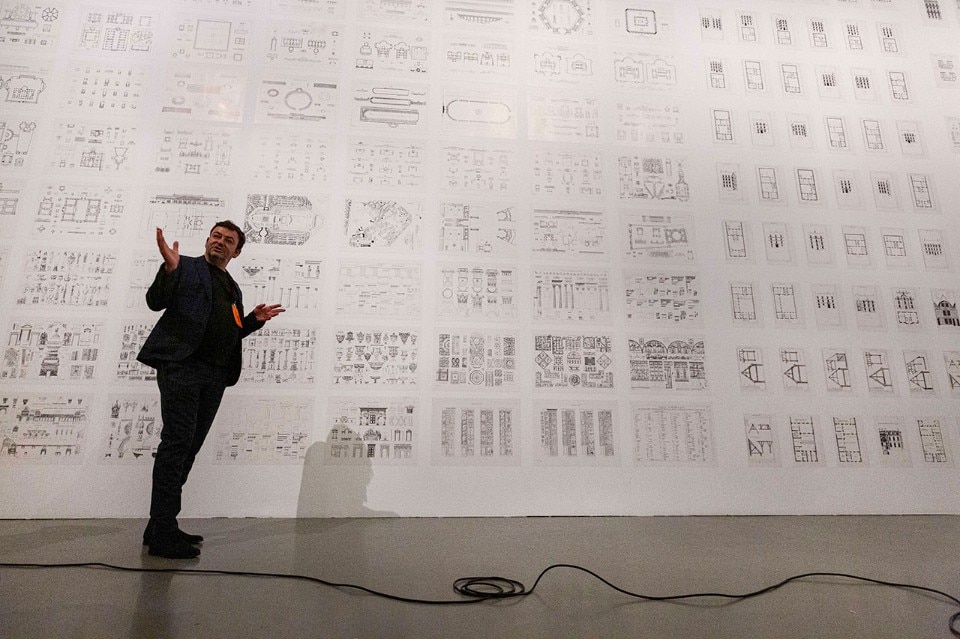

Inside the old power station, we meet architect, theoretician and teacher Lapierre, in order to visit his “Economy of Means” exhibition. Lapierre teaches at the school of architecture of Paris-Est, where he collaborates with the same team that helped him realize the curatorial program of the Portuguese Triennale. This far-reaching Triennale hosted many associated projects, educational activities, the Triennale Millennium bcp Awards, and it culminated with the Talk, Talk, Talk conference at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

According to the chief curator, the aim of “The Poetics of Reason” is to “reaffirm that architecture is still based on rationality, by trying to define the specificity of the latter within the practice”. To explain the complex logic of this “architectural rationality”, Lapierre uses a metaphor of the Doric column, which is “at the same time a structural element and a sculpture” stressing that “architecture is free, and an added value to a series of needs”.

While visiting “Economy of Means”, Éric Lapierre made a point that he made sure to emphasize for the entire duration of the Triennale, for example during the press conference that followed our meeting: “Since the beginning of the century, we have been spectators of the rise of iconic buildings, which add nothing to the collective experience of architecture”.

Although Lapierre believes that every good building must have a strong image, the buildings he mentions only seem to only have a strong image, and nothing more: “These strong images sure take your breath away, but once you are left without air, you can no longer speak!”.

As a consequence, the French curator sees a lack of critical spirit as well as a lack of debate on architecture. Lapierre sees these iconic buildings as the architectural translation of the pervasive populism that characterize today's politics, since both phenomena originate from a tendency to trivialize everything.

Since the beginning of the century, we have been spectators of the rise of iconic buildings, which add nothing to the collective experience of architecture

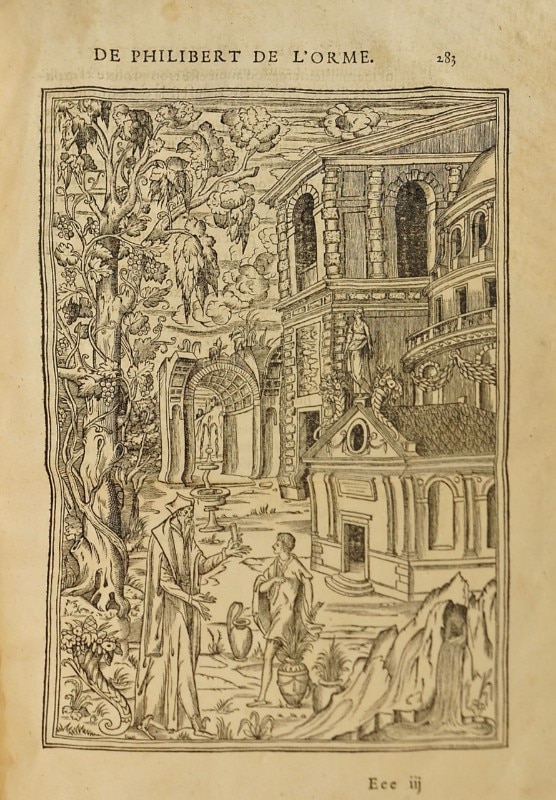

What makes a building rational, then? I ask him. “What is rational is intelligible, has a logical form and is therefore transmissible: architecture is a form of knowledge, which is why I opened the exhibition with (a part of, A/N) an illustration by Philibert de l’Orme, l’Allégorie du bon architecte[1]” This representation of the master-disciple relationship aims to bring the visitor’s attention back to the priority of the curators’ team: transmitting the discipline.

Lapierre also talks about the importance of the constructive logic of architecture: “for us it is essential to create a debate, to design buildings that allow us to express disagreement”. While this may sound like a form of nostalgia for the “dear old days“ of the profession, Lapierre wants to tackle the climatic problems of this era, from climate warming to the unprecedented lack of resources, blaming these iconic buildings for participating in the draining of resources that have now become extremely valuable.

What is rational is intelligible, has a logical form and is therefore transmissible

“Economy of Means” serves as a counterbalance to these statements. Through a series of quotes and references, from Palladio to OMA, they support the ideas of the curator. The chosen projects are represented through drawings and models, instead of 1:1 mock-ups. The pedagogical approach lies at the heart of the exhibition, since the Triennale's aim is to open the debate on architecture to a wider public.

This curatorial approach is characterized by clear statements and a broad range of references. Sometimes, however, the links between the references aren’t very clear, perhaps because some parts of the exhibition remind us of a kind of wunderkammer. The “Inner Space” exhibition by Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli (by Socks and Microcities) shows that every architect has their own ever-changing, always redefined idea of what architecture is. And, if you think about it, a wunderkammer is the place where an individual collects different things, ideas and references over time: thus, it makes sense that, throughout the exhibition, the imagination of the curator is being shown without needing to have a clear logic.

If we want to find out what Lapierre means when he talks about “architecture of reason”, perhaps his essay “L’ordre de l’ordinaire” is useful. Architecture sans qualités (2005). Here, the chief curator talks about “architectural banality” and compares monuments to utilitarian architecture: the former are singular elements that embody the idea that a society has of itself, while having a character of permanence. The latter, mainly intended as residential buildings, are built around the former, and are a ‘commonplace’ of architecture that requires “wisdom, calm and privacy”. When visiting Economy of Means, we get the impression that Lapierre wants to highlight that very calmness, modesty and economy of the common building, without ever losing an expressive dimension of architecture.

And as the visit comes to an end, in the room dedicated to the models of 21st century architecture, we find a particular building. An updated and – as we are told – involuntary version of Koolhaas’ The City of the Captive Globe. Here, among other buildings, the curator focuses on the model of Shin Takasuga’s Railway Sleeper House (1970).

Lapierre lingers in front of the building, which has a surprising feature: it is entirely made with sleepers recovered from the old train tracks. The building, in its “economy of means”, makes its logic evident, and is both modest and expressive: one could almost call it “a subtle icon”. The opacity of those wunderkammer-like parts of the “Economy of Means” exhibition fades into the background, as we discover the “architecture of reason” that Lapierre wanted to tell through “The Poetics of Reason”, the manifesto of a radically modest and appropriately contemporary architecture.

Shin Takasuga, Railway Sleeper House, Miyake, Japan, 1970

Opening image: “Economy of Means”, exhibition view, part of “The Poetics of Reason”, Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2019, MAAT Central Tejo, Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. Photo © Fabio Cunha

Nota: [1] “Allégorie du bon architecte” from Philibert de l’Orme, The First Volume of Architecture (Le Premier Tome de l’Architecture), 1567.

- Exhibition title:

- “Economy of Means”

- Dates:

- October 3 - December 2, 2019

- Chief curator:

- Éric Lapierre

- Part of:

- “The Poetics of Reason”, Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2019

- Curatorial team:

- Éric Lapierre with Sébastien Marot, Mariabruna Fabrizi, Fosco Lucarelli, Ambra Fabi, Giovanni Piovene, Laurent Esmilaire, Tristan Chadney

- Sede:

- MAAT Central Tejo

- Address:

- Avenida Brasília, 1300-598 Lisbon, Portugal