The use of drones in architecture is relatively new but seems to be a rapidly expanding practice. Already offering new visual perspectives through aerial photography and videography, could they actually become architects’ best friends, performing varied tasks such as delivering construction material, surveying building sites and even assisting in the construction process by carrying out all the heavy work? Over the past years, French architect Stéphanie Chaltiel has been experimenting with these flying machines to develop a new construction method involving earth that puts them at the core of the process. We reached out to her to learn more about her research and technique.

Your approach seems to go beyond the standard use of drones and proposes to involve them in the construction process itself. Could you tell us how you came up with your idea?

In my experience talking about drones and their uses in different industries tends to divide the crowds. Outside of aerial photography and videos, mechanical actions performed by drones were already explored at the ETH in Zurich and the MIT in Boston a few years ago with weaving, spraying paint, pick and place actions. The research that I have been developing over the past three years – which is funded by InnoChain and the Europe Horizon2020 Marie Curie programme (a vast and multidisciplinary research programme supported by the European Union that aims at encouraging technological innovation in the continent) – aims at revisiting principles of shotcrete using drones fitted with a spraying hose to apply different layers of biomaterials (non-cement based mortar) on a light formwork. This method involves adapting immediately available technologies that were never embedded in a common system before. A lot of the work is to calibrate the tool, the matter and the form so that the system can work. And, of course, it also offers new aesthetics.

How does it work practically and what are the characteristics of your method concerning the skeleton of the building, the programming of the drone, the costs involved and the choice of materials? Also, most of the structures that you developed so far are “monolithic earthen shells”. Why this specific shape and why earth?

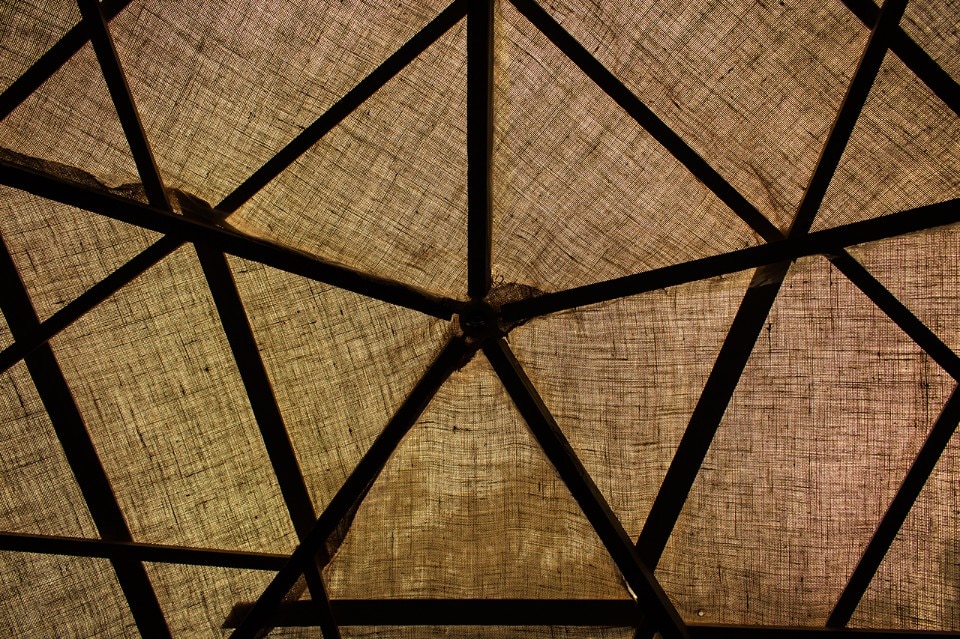

The idea is to use easily mounted skeletons or formworks – like geodesic domes, grid shells, tensed textiles over arches or inflatables – to be then drone sprayed with natural materials following a sequence where each mix contains different ingredients and drying times to be respected. For the 4m domes we have recently built, the first light formworks were mounted in just a few days by two to six people. The spraying phase allows the coating of a 50sqm structure with a thick layer of material in only 15 minutes. Currently, the clay materials and the light formwork are cheap and can be recycled, whereas the drone flights cost around 2.000 euros for a week of construction. Regarding the material, I fell in love with raw earth architecture more than 20 years ago for its tactile aspect, the varied textures that can be obtained with it, the many different ingredients that can be combined in the mix (lime, sands, linen fibers, oils, etc) and more importantly how nice it feels inside an earth building.

You started your career in French Guyana and Mexico “developing innovative sustainable housing techniques using local materials, fabricated by hand together with local dwellers”. A rather low-tech approach compared to your nowadays’ use of drones. Could you tell us more about your early experiments and how they influenced your current work?

During my time working in both tropical and emergency contexts, I had the opportunity to identify the repetitive actions that can be eased by robotic operations. Unless you build a shelter by hand – including all the micro steps, such as receiving the clay and storing it, amongst many other – you can't foresee everything that will happen on site. No matter how much you plan. I also have a real passion for enjoyable manual crafts that, in my view, could be used more at the building scale if the drones actions facilitate some difficult tasks.

A lot of the work is to calibrate the tool, the matter and the form so that the system can work. And, of course, it also offers new aesthetics.

Could this technique compete with other robot-assisted construction methods such as 3D printing? Could it be used to build larger structures?

The drone spraying technique involves different techniques whereas the extrusion one is focused on one single phase construction. The spraying has the advantage of achieving large scales without the need to build scaffoldings or to transport massive robots or cable bots on site. Extrusion requires an infrastructure larger than the resulting construction, which is not the case with drone spraying. When dismantled the drone fits in two pieces of luggage, and the spraying pump on wheels can reach any remote site easily. The uses of drone spraying are therefore manifold compared to extrusion. Also, our technique allows us to give an outer coating to existing facades or to realise inside walls. At the moment we are working on embedding sensors in the system so that the thicknesses can be varied and controlled. In addition, the goal is to develop further the artificial intelligence of the drone so that it can ‘train itself’ in recognising cracks and repair them timely. But this is the next phase!

You are continually refining your process and methodology through the organisation of workshops and public performances. Can you tell more about the structures that you built at Domaine de Boisbuchet this summer and during the latest London Design Festival? Unfortunately, after only a few weeks, the first one collapsed: Anything specific that you learnt from that failure?

Boisbuchet has been the best fabrication workshop I ever had the chance to run. The workshop team was highly efficient, and everything was facilitated. We had a very motivated group of students, some of them coming from Dubai with my colleague Muhammed Shameel. We built a geodesic skeleton in only one hour and then attached to it 2.000 little jute bags filled with hay, before passing to the drone spraying phase. It was also the first time that we could highlight how efficient the drone spraying technique is as the whole dome was coated in only 10 minutes. The location by the lake was magical, and I think everyone loved the dome. When entering inside, even though the structure had no doors, you would feel no external sounds. Also, we covered the interior with textiles, something that gave it a very gentle touch. It was heartbreaking to learn that it felt. It would have needed one more week at least of drone spraying to gain enough thickness and one month of being protected by the rain to be viable permanently. But it was certainly an incredible learning that we put into action for the London project.

During my time working in both tropical and emergency contexts, I had the opportunity to identify the repetitive actions that can be eased by robotic operations

The geodesic frame that we used there was much stronger and we left the top of the dome covered with only fabric and transparent plastic sheets, so not to apply weight on top. Finally, we made the entrance much smaller and inserted two poles instead of having the huge diamond-shaped entrance. It worked! It rained heavily during three days and the structure has resisted without being covered. Actually, being our project during the London Design Festival located on Southbank, the most challenging aspect of it was having to deal with the city’s anti-terrorism measures! Furthermore, it is not permitted to fly drones in London and aviation laws change very often. The only way that we found to work on the structure was to build it inside a netted volume. I prefabricated 35 triangles containing a multitude of little bags filled with hay. I was then joined by Barcelona earth architect Fabio Gatti and Pete Silver from Westminster for the fabrication phase on site which lasted only two days. We also pigmented in blue the clay and lime mix and it was the first time we’ve managed to obtain colour with the drone spraying technique. The drones spraying sessions were designed to fit into a performance format so that people walking along the river could stop by. Which they did! It was a fantastic idea from Will Sorrell, the director of Design Junction, who trusted the project from the beginning.

Apart from experimentations, on which real-case projects are you currently working?

The drone that we have been using in the last mud shells projects belongs to the Louvain School of Engineering and has been fabricated by Michael Daris who pilots it with Sébastien Goessens. We have then adapted it to fit a hose by Euromair – a company specialised in the production of tools for the building industry. This has been a great achievement for us in the development of the technique. We are now able to have a constant flow of materials and we are ready to build at a much higher/larger scale. The equipment we are currently using are therefore not off the shelf and have been fabricated only for this research. We are now working actively with Euromair to test large-scale coating of existing facades. At the moment I am also discussing the realisation of a cliff house in Vietnam, that the client imagines as a birds nest. High and hard to access areas are definitely projects where it would be relevant to use the drone spraying technique.

Opening image: Spraying with drones during a workshop at Domaine de Boisbuchet, summer 2018, photo Alina Cristea © CIRECA Domaine de Boisbuchet

With over 10 years of experience, Stéphanie Chaltiel is a French architect who studies and explores the use of digital technologies and earth construction for sustainable housing solutions. She worked for Bernard Tschumi in New York, for OMA in Paris, for Zaha Hadid in London. She has valuable experiencse in countries such as Mexico and French Guiana. She taught for five years in France and London and at SUTD in Singapore. Chaltiel also directed the AA Visiting School in Lyon and Indonesia.