This article was originally published in Domus 969/April 2013

In the Easy Jet queue at Gatwick, the gate attendants check their manifest. “There’s 170 men and 20 women on this plane. Must be a football match!” Well, no. It’s not football but property that’s gathered us here at the crack of dawn. We, and 20,000 other delegates from around the world, are heading to MIPIM (Marché International des Professionnels de l’Immobilier), the international property fair held annually in Cannes. It’s where developers, planners, agents, investors, regions and cities, as well as those further down the food chain, like drainage consultants and architects, get together, promote, network and, most importantly, swap business cards.

The first thing mipim delegates ask when they arrive on the Promenade de la Croisette is, “What’s the mood?” What they mean by mood is a weathervane of economic sentiment, a feeling, a vibe generated by the concentration of so many property types in one place. (The replies, you’ll be pleased to hear, include words like “better”, “upbeat”, “happy” and “relaxed”, suggesting a general sentiment of economic unslumping).

MIPIM’s geography is centred around the romantically named Grand Palais, a huge, angular, cantilevering future-shock of an expo building that perches on the dockside like cheap sci-fi scenography and is nicknamed The Bunker. Its halles stretch out in long horizontal horizons packed with a tumult of expo stands. Each is pitching something, though it’s often hard to pin down what that something is. Sometimes they are pitching to developers: a car-park company boasts of managing 750,000 parking spaces worldwide; an agency is selling off Polish military land and giving away silver bags. Sometimes developers are pitching buildings to investors. One, for example, is decked out like a St Petersburg palace: golden furniture, pilasters, duck-egg wallpaper. On its walls hang gilt-framed oil paintings of what look like second-tier airport hotels or the regional headquarters of a photocopy leasing company.

Stands often come with props: a signed picture of a Lithuanian boxer on a bed of AstroTurf, a Russian spacesuit advertising So Toulouse (the tourist office of Toulouse), and fake Mondrian paintings (many of them, perhaps something to do with Holland?).

The stands vary in sophistication: from high-end developers like mebe, who are using MIPIM to announce themselves to the world, to the bombastic in cyclopean models of Respublika (Europe’s biggest shopping mall—though it’s difficult to tell if it actually exists), and bizarre encounters that take place down the quieter (and cheaper, one assumes) back passages (Family Fun malls, anyone?). Yet at the same time there are stands like GE Capital Real Estate (“Imagination at Work”), whose mystery is matched by the fear of knowing what their true global influence might be. Among all this, it’s a challenge to discern what is real and what is speculative, what is solid and what is pure vaporware.

As soon as you enter The Bunker, you lose all perception of space. You walk in huge circuits, around and around, finding yourself back in the same place without knowing exactly how you got there. Or you might walk from the same spot, the same way, only to find something else as though the whole arrangement had been shuffled while you weren’t looking.

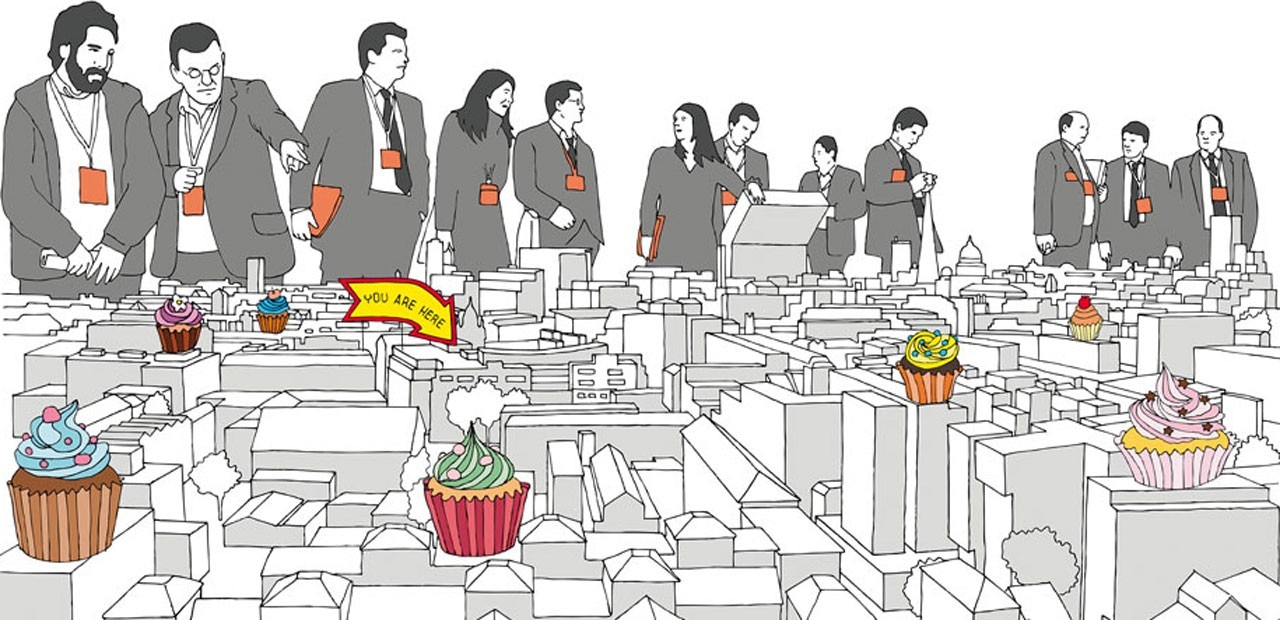

Passing model after model, rendered in glowing Perspex on floating islands of live-edge or hyperreal model railway fantasies, everything begins to bleed into each other. Even worse: a combination of expo-hypnosis and low blood sugar makes it difficult to identify where the models end and the plinths, furniture and free gifts begin. Scales merge so that buffets of Belgian or Scandinavian finger food begin to look like regional development plans. The giant spindles of plants in huge abstract vases (and these ones are particularly sickening, resembling over-scaled versions of Gunther von Hagens’s plastinised veins) seem like they might be cities for 20,000 people. All this stuff delivered and hastily assembled in the Palais becomes interchangeable, transmutable, equivalent.

I wander into the Logistics Pavilion, which sets out investment opportunities in transportation hubs across Central Europe. Models of sublime banality show light industrial sheds with articulated trucks plugged into them, their tarmac skirts set into non-specific forests. They are models with such a clear-eyed focus detailing the minutiae of the modern world’s base-level infrastructure. Also of note here are the large-format photographs of unknown motorway intersections.

Scales merge so that buffets of Belgian or Scandinavian finger food begin to look like regional development plans

The most fascinating stands, however, are those dedicated to cities and regions. Here it’s not exactly projects that are presented but ideas, concepts and sentiments asking for your buy-in. The Lille region, for example, brands itself as “Amazing” (followed by the more serious but unintelligible slogan, “At the heart of the richest consumption area in Europe”). It’s just one of many whose scale and presence range from apartment balconies decked out with banners reading “Coventry & Bristol” like a third-round FA Cup replay, to the big tents pitched by the water’s edge for London, Paris, Moscow and the mythical sounding Krasnodar Region (somewhere in the Russian Federation, geography fans). The Krasnodar Region tent boasts giant models oscillating wildly from the prosaic (an exquisitely correct model of a tiny timber processing plant) to the fantastical (a Formula One track that also seems to house a space port) and a Russian-speaking robot. According to MIPIM veterans it lacks the leggy Krasnodarian blonds of mipim’s past. (Note: though everything looks fresh to your novice correspondent, regular MIPIM-ites report that many of the stands and models are recycled year after year.)

It’s in this aspect that MIPIM begins to reveal something you can’t really see elsewhere: that cities and regions are here not as the places you and I know as the places where we live, work and love. They’re here as brands, as investment opportunities, as businesses. mipim is where cities talk to money. They sweet talk, whisper, shout (and quite possibly also cry) to money. But it’s never clear where money is. Everyone here is selling, though exactly what is for sale seems mostly slippery. And who they are selling to remains, for the most part, unexplained.

There’s a ruthlessness to all this. I’ll try and quote a statistic that I barely noted down at a party in a marquee on the beach, distracted as I was by the dull thunder of crashing waves and a lighthouse blinking blood red out over the dark sea.

It’s not the figures that matter, but the sentiment—and the fact that it’s the Deputy Mayor of London saying it: “Of the world’s current top 600 cities, one third of these developed-market cities will no longer make the top 600 in 30 years’ time.” This reveals something more than first-world paranoia. Of course, you and I probably imagine cities to be places where we live and work, places run by democratic government. But at MIPIM, cities are something else: investment vehicles and brands. In other words they are competitive market entities. And they are competing fiercely with each other for investment, growth and status.

This is the not-so-subtle subtext of almost everything here. It’s what is written large in the giant model of London inside the London stand (with the tagline “The Winning City”). It’s in the way the model lights up with a techno-blue glow to reveal current and projected developments. It’s there in the Local Authority stands for Southwark, Enfield, Croydon and Newham, pitching the possibilities for capital to take urban form within their municipal boundaries. It’s there as Mayor of London Boris Johnson rides into town on a Boris Bike to spend the day using a rumour that Nicolas Sarkozy and Carla Bruni might be relocating to London as a stick to bash Paris. “I am the mayor of the sixth-biggest French city,” he proclaims. It’s there even in the slick, cool Manchester stand where Professor Brian Cox makes an impassioned plea for investment in science and education. And it’s also forlornly visible in the piles of brochures abandoned among half-drunk cups of coffee and orange juice.

For architecture, MIPIM is a lesson: despite the thousands of square metres of models of buildings, architecture remains peripheral to the proceedings. It’s like the Total Perspective Vortex, the ultimate existential torture device invented by Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Like the TPV, MIPIM reveals architecture’s infinitesimally small scale in comparison to the universe of development. This horror, though, is important. The pain and anguish of this awful revelation might help us to re-engage with the project of the city, it might help us to comprehend the mechanics of city-making, and it might help us to understand exactly what cities in the early 21st century have become.

In the EasyJet queue back at Nice, MIPIM survivors check their business card bounty. They flip though their stacks in groups, adding aide memoirs (e.g. “Fat man at bar”) or swapping duplicates like playground football card transactions. Somewhere else, one hopes, others are doing the same with our own cards. And perhaps that’s the real purpose of mipim. Even if nothing actually happens, even if no deals are struck, it’s the fact that we’ve all come here to play and be played, even if there’s no actual game to play. Sam Jacob Architect and critic, director of the architectural firm FAT