It is needless to say (or perhaps not) that this very system creates congestion: the unsustainability of a one-way process moving in the direction of catastrophic and increasing entropy.

That is why the question of food (the first and most fundamental form of energy) must return to the center of thinking about habitat, because living means, first and foremost, having shelter, food and water. And although the statement may seem obvious, the data show that it is not so if rich Europe counts more than 5 million homeless people, and the response to the demand for food in the city counts for up to 40% of its ecological footprint (only for transport, packaging, storage and disposal of food products). That is why we can't pretend that it is not our problem (the architects), but on every scale and with each occasion, we must return to thinking about food and shelter: productive land and constructed land. The term "return" is used because, as we can see, for example, in Rome's famous 1748 Nolli map, the city contained endless gardens inside and outside the walls, still intact even after the Rome's transformations as Italy's capital in 1870.

As the designers state, the protagonists of these "green sites" are in fact "seniors' centers, churches, scout groups, social organizations and environmental groups, the disabled, youth, women," and in this sense, the care of these spaces become, above all, an opportunity to "create community" or, in other words, to weave new relationships between people.

Over the course of the 20th century, the city - first industrial and post-industrial - became an organism that, in terms of its basic needs is fed daily from the outside, cleansing itself and returning waste products again to the outside

What emerges from this story is a need for the "country in the city; "representing a desire for a new relationship with the land and food, which we learned about in recent years from the extraordinary experience of Carlo Petrini and Slow Food, and which has been demonstrated everywhere by the success of the Campagna Amica (country friend) project by Coldiretti (the main Italian farmers organization) with its amazing farmers' markets. But there is also the need for a kind of city where population density is accompanied by patches of land free from asphalt and cement, patches from which the land emerges and where people can dirty their hands, manipulate, transform and cultivate the land, and maybe see together the egg and the chicken, sheep or other farm animals.

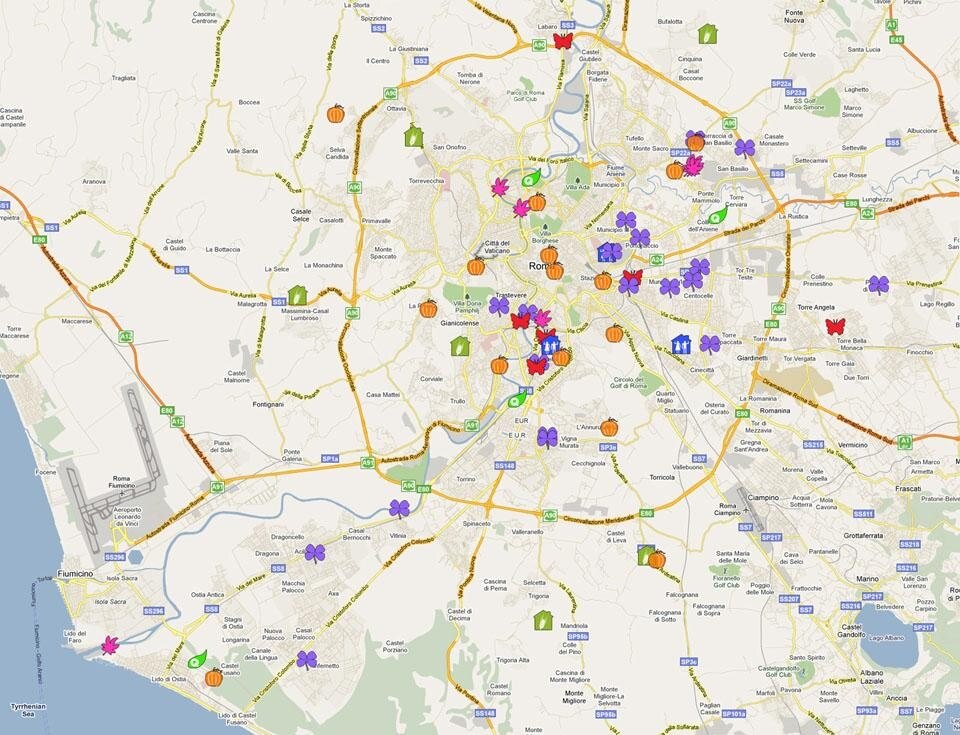

Over the past 20 years, in a territory (the Province of Rome) in which the agricultural areas have been reduced by one-fifth, this bottom-up collective action represents not only a form of resistance but the experimentation of an alternative: that of taking over the city (and making it our own) not through the acquisition of private property but by taking care of a piece of public space, producing new environmental, economic and social dynamics.