The great fashion brand/big international architecture firm binomial is now something usual, part of a cultural and market language where the boundaries of the two realms are increasingly blurred, with architecture landing directly onto the runways and into the collection concepts. The origins of this exchange go far back in the decades, but early- millennium years are the time when the most symbolic merging takes place, translating into a series of architectures that – with a relevant contribution from the specificity of their locations – created a new typology: the sculpture-store capable of becoming an identity signal within the urban context. Dejan Sudjic presented one of these episodes in July 2003, on Domus 861, also finding an opportunity to sketch a snapshot of two outstanding names of the international architectural star system, by the time of their consecration.

Commerce and culture

I suspect that Jacques Herzog and Rem Koolhaas used to see themselves as the Picasso and Braque of contemporary architecture, effortlessly towering over their peers in the same way that the two cubists once monopolized painting, ‘roped together like mountaineers for the final onslaught on the summit’, as Picasso put it.

Herzog and Koolhaas have indeed set out to collaborate with each other from time to time. There was talk of a joint project for Tate Modern before Herzog and de Meuron won the competition to build it on their own. Later they worked on a plan for an Ian Schrager hotel in New York, but it was torpedoed by Koolhaas’s way of breezily antagonizing his client. Herzog loyally declined to take on the project by himself.

It is a relationship that is more of a symbiosis than a partnership. The restless, gifted but erratic Koolhaas holds the architectural world in thrall like a circus ringmaster, and it responds by docilely treating him as its great thinker. Herzog, on the other hand, is the subtler and calmer of the two. Between them they have transformed the architectural debate of the past 20 years, Koolhaas by trying to get people to focus on an urban landscape that is changing with dizzying speed; Herzog by inventing a dazzling series of building types and new ways of building that sustain a whole school of followers.

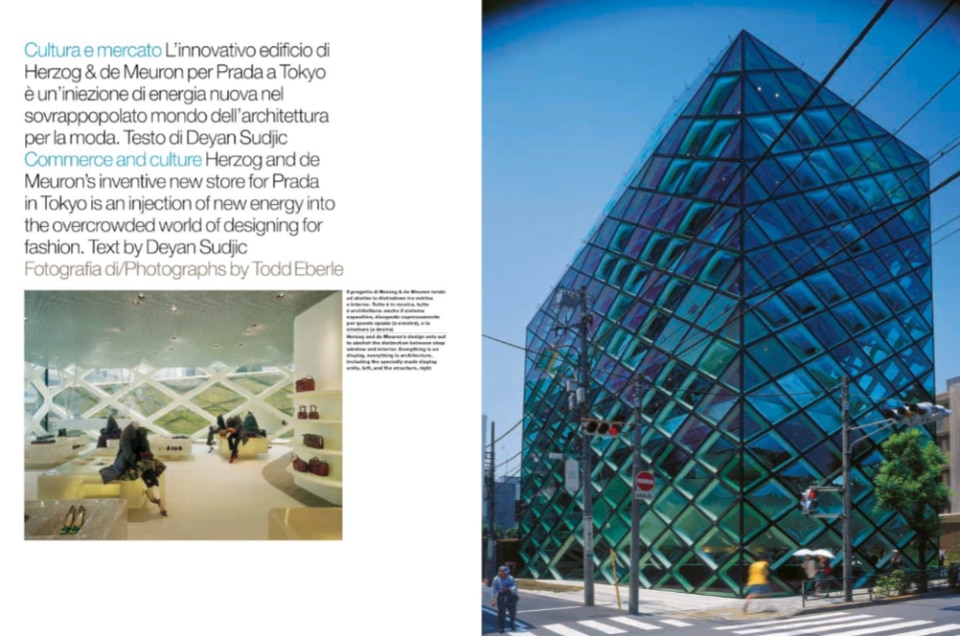

Herzog and de Meuron have in a sense reached cruising speed. Each of their projects builds on what they have already done in a brilliantly inventive way. Every building offers a fresh way of looking at architecture. Their new store for Prada in Tokyo comes hard on the heels of Koolhaas’s much publicized New York Prada flagship. Herzog and de Meuron’s design in Tokyo, at an estimated $80 million, may have cost more than the $50 million New York shop, but architecturally and urbanistically it is much more ambitious, more accomplished and refreshingly free of hyperbole.

For Herzog, a shop is nothing more or less than a shop; it is not an excuse to construct a new world order. But it is a very beautiful shop, put together with the finesse of Japanese craftsmanship and Swiss determination to create a richly satisfying work of architecture.

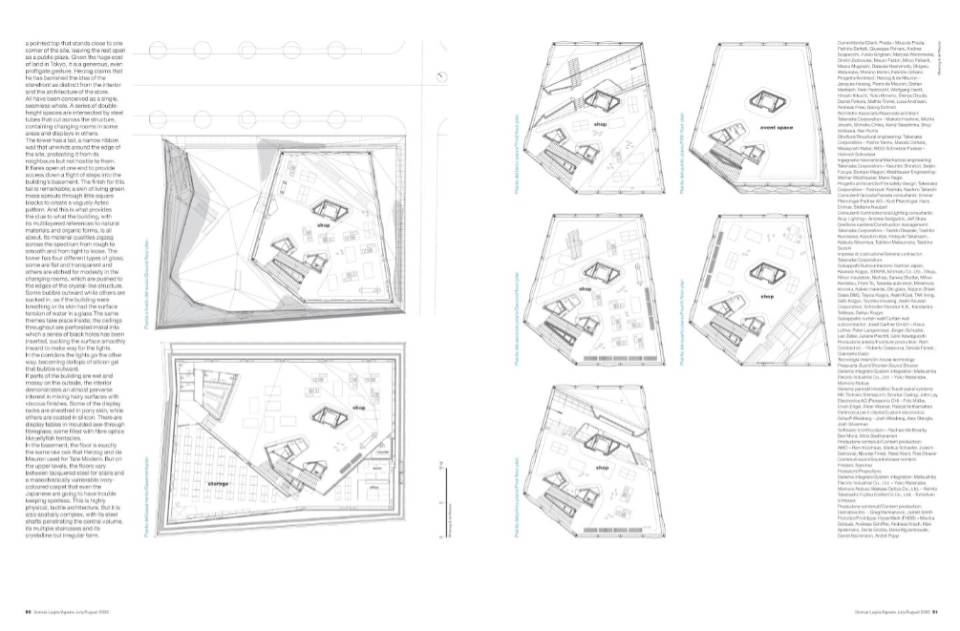

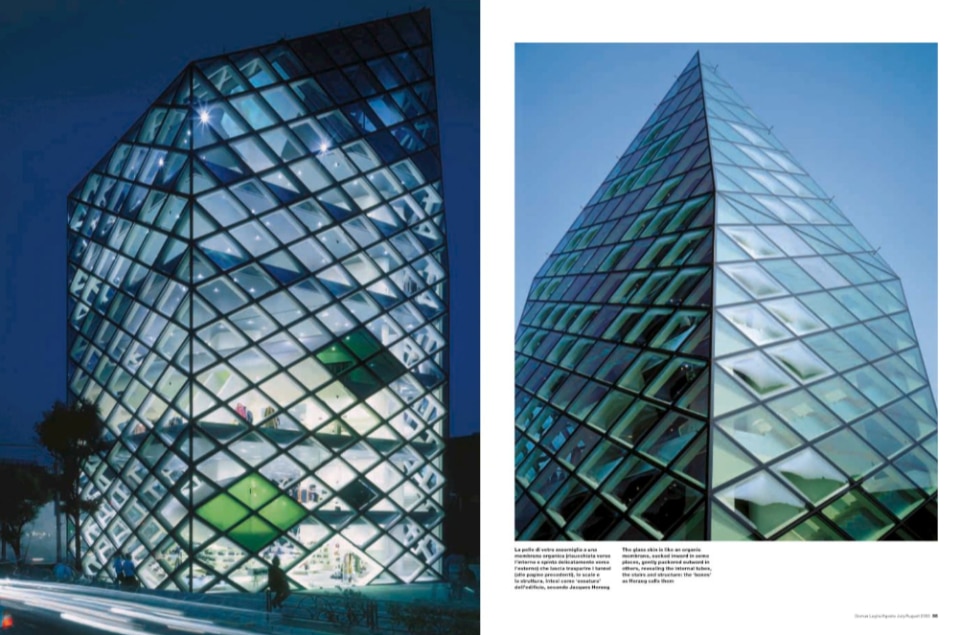

Prada is throwing almost as much cash into contemporary architecture as it has put into building gigantic sailboats for the America’s Cup, with much the same combination of genuine enthusiasm and image building. It succeeds in getting the company talked about, but it also needs to sell silver shoes, nylon bags, suits and its skirts, cosmetics and underwear. Herzog and de Meuron make that process a comfortable and memorable one. In return, Prada has given them the chance to smuggle an extraordinarily physical building – an extruded glass crystal braced by a steel mesh that gives it the appearance of a beehive or a honeycomb from some angles – into the centre of the city.

Prada is on Omotesando, Tokyo’s version of Milan’s Via Montenapoleone, London’s Bond Street and all those other streets in cities from Los Angeles to Shanghai where fashion brands huddle together for warmth, unsure whether they need the address more than it needs them.

But it is not quite the same as its peers, not least because Tokyo’s architectural crust is so fragile. The big, glossy buildings that make Tokyo look like the city of the future are adrift in a sea of little wooden houses that sprawl randomly everywhere. By a process impossible for outsiders to understand, this area of Tokyo, which trickles down the hill from the teenybopper haven of Harajuku on the edge of the Yoyogi Park, has been identified with fashion since the 1960s.

It is here that Shiro Kuramata did his first design work for Issey Miyake and John Pawson designed a now-vanished store for Calvin Klein. To make an architectural fashion statement here, it is no longer enough to create a shop interior, no matter how exquisite. To stand out in this shifting seascape of an environment, you need to build something on the scale of a super-tanker, if you are really going to register. There are certainly plenty of such projects in the pipeline.

Years ago Kenzo Tange built the now unremarkable headquarters of Hanae Mori here. Tadao Ando did a kind of fashion mall. Louis Vuitton has Jun Aoki’s svelte structure of glass and metal mesh, while Toyo Ito is working on a project for Tod’s and Kazuyo Sejima is building a big new store for Dior.

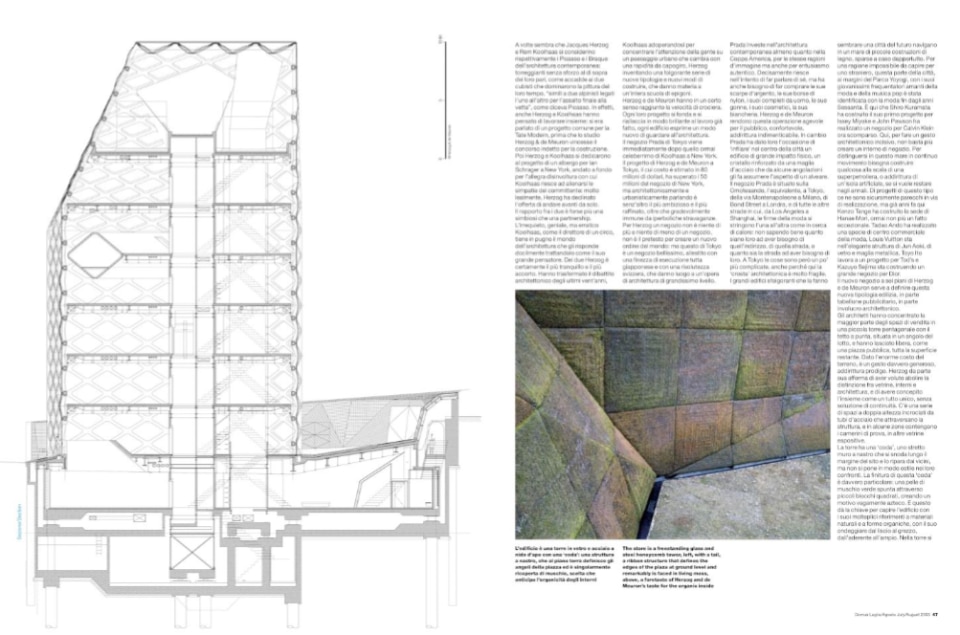

Herzog and de Meuron’s new six-level store serves to define this new building type: part advertising billboard, part architectural gift-wrapping. The architects have piled most of the store into a little five-sided tower with a pointed top that stands close to one corner of the site, leaving the rest open as a public plaza.

Given the huge cost of land in Tokyo, it is a generous, even profligate gesture. Herzog claims that he has banished the idea of the storefront as distinct from the interior and the architecture of the store. All have been conceived as a single, seamless whole. A series of double-height spaces are intersected by steel tubes that cut across the structure, containing changing rooms in some areas and displays in others.

The tower has a tail, a narrow ribbon wall that unwinds around the edge of the site, protecting it from its neighbours but not hostile to them. It flares open at one end to provide access down a flight of steps into the building’s basement. The finish for this tail is remarkable; a skin of living green moss sprouts through little square blocks to create a vaguely Aztec pattern. And this is what provides the clue to what the building, with its multilayered references to natural materials and organic forms, is all about. Its material qualities zigzag across the spectrum from rough to smooth and from tight to loose. The tower has four different types of glass; some are flat and transparent and others are etched for modesty in the changing rooms, which are pushed to the edges of the crystal-like structure.

Some bubble outward while others are sucked in, as if the building were breathing or its skin had the surface tension of water in a glass The same themes take place inside; the ceilings throughout are perforated metal into which a series of black holes has been inserted, sucking the surface smoothly inward to make way for the lights.

In the corridors the lights go the other way, becoming dollops of silicon gel that bubble outward. If parts of the building are wet and mossy on the outside, the interior demonstrates an almost perverse interest in mixing hairy surfaces with viscous finishes. Some of the display racks are sheathed in pony skin, while others are coated in silicon. There are display tables in moulded see-through fibreglass; some filled with fibre optics like jellyfish tentacles.

In the basement, the floor is exactly the same raw oak that Herzog and de Meuron used for Tate Modern. But on the upper levels, the floors vary between lacquered steel for stairs and a masochistically vulnerable ivory-coloured carpet that even the Japanese are going to have trouble keeping spotless. This is highly physical, tactile architecture. But it is also spatially complex, with its steel shafts penetrating the central volume, its multiple staircases and its crystalline but irregular form.