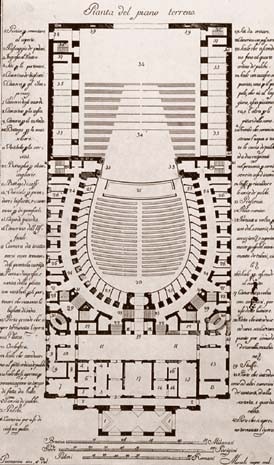

Seen from the piazza, Giuseppe Piermarini’s neoclassical La Scala Theatre has something of the Milanese character about it: elegant but restrained and hard-working, it rests its refined upper stories – carved from pale-cream Viggiù marble – on a solid grey granite base. On August 3, 1778, the audience of 2,200 that attended the gala opening was entertained by Antonio Salieri’s melodramatic opera Europa Riconosciuta.

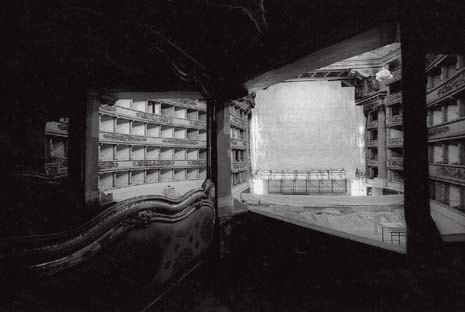

Today a different kind of melodrama is on offer. On the other side of the boarded-up proscenium arch, the visitor is confronted with a scene of utter devastation. The entire stage and backstage area has been gutted as far as the perimeter walls. The impression that some cataclysmic event has taken place is reinforced by the large crater that has opened up where the stage once was; on the other side of this abyss, water gushes into the void from an overflow pipe.

This apocalyptic scenario is not the product of some demented set designer’s imagination. It is the result of the Milan city council’s bitterly contested decision not just to carry out a much-needed backstage upgrading, but also to bring in Mario Botta to make an architectural statement out of the process.

Opera houses stir deep passions. More than a city’s art museum, more than its concert hall, railway station or airport, it is an opera house that really marks out a city’s claim to be a metropolis rather than a provincial outpost. Look what it did for Sydney: those antipodeans understood the concept well enough when they commissioned Jørn Utzon’s daring new temple of opera, which has become both landmark and logo. Cardiff, on the other hand, managed to betray its essentially blinkered view of its own potential when Zaha Hadid won a competition to design an opera house – and then refused to build it.

But the storms provoked by new opera houses are as nothing compared to the passions unleashed by the renovations of existing ones. And of all the world’s historic opera houses, few command such deep-rooted loyalties as La Scala. When an Italian satirical news programme hired a helicopter to film the scene of devastation behind the proscenium arch, there was an outcry.

Carla Fracci, the doyenne of Italy’s ballerinas and head of the Rome Opera corps de ballet, exclaimed that ‘our theatre has gone; we have lost it for ever’; veteran set designer Luciano Damiani, who has worked at La Scala for more than 50 years, declared that it was ‘a disaster’. It has long been recognized that the structure was in need of a major overhaul. In 1990, the incoming general manager, Carlo Fontana, warned that the theatre was suffering from ‘severe health problems’ and was ‘technically inadequate’.

At a press conference called last year to mark the beginning of the estimated 859-day renovation, prior to the company’s move into its Vittorio Gregotti-designed temporary home in the northern suburbs, Milan’s deputy mayor, Riccardo De Corato, said that the work was necessary to ‘allow those who use the theatre to live and work in optimal conditions’. He also gave enemies of the €40 million project plenty of ammunition by comparing it enthusiastically to ‘a four-star-hotel’ and ‘a stadium for 35,000 people’.

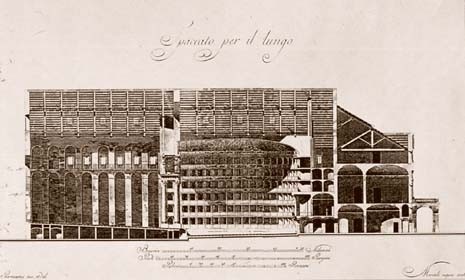

The renovation of the backstage area to accommodate the increasingly extravagant, high-tech requirements of modern opera staging is one that has been embraced by most other leading historic opera theatres, from Covent Garden to the Vienna Staatsoper. At La Scala, this purely functional part of the edifice was last revamped in 1921, and in its most recent, pre-demolition state, it was a patchwork of ad-hoc solutions. One of the few parts considered worth saving was the ingenious wooden stage designed by Lorenzo Sacchi in 1937, made up of a series of panels raised and lowered by hydraulic pumps. This has been removed; Milan city council has promised that it will be reassembled in a pavilion of the former Ansaldo factory, which is destined to become a part of the new, extended La Scala Museum.

As for the auditorium (already extensively rebuilt after bomb damage during the Second World War) and the so-called avancorpo, or front-of-house area, these are being restored, in line with the modern conservative creed, by a team led by Elisabetta Fabbri, who is also coordinating the decorative elements of the soon-to-be-reborn La Fenice opera house in Venice.

Fabbri is keen to point out that in some ways, the theatre that is due to be returned to the city in December 2004 will be closer to its original 18th-century state than it has been for years. Under 11 layers of paint, areas of period ochre-tinted marble have been found; terracotta tiles have emerged from beneath stacks of linoleum in the boxes; fragments of red silk wall coverings from the early 19th century have been exposed. The intention is to restore or (in the case of the wall coverings) reproduce these elements in order to return as far as possible to La Scala’s decorative origins.

The restoration of La Scala’s interior, however, is relatively uncontroversial, as is the need to renovate the stage and stage machinery, which is accepted by all but the most diehard sentimentalists. What worries many is what is going up in place of the temporary backstage roofing solutions that have been adopted over the years, and how this has been imposed on the city.

The renovated La Scala is essentially the work of two architects, Giuliano Parmeggiani and Mario Botta. At the request of Milan’s city council, Parmeggiani drew up a project whose intention, he says, was to ‘define functionally what were the technical needs of a modern opera house’. No competition was held, even though Italian law prescribes this for ‘works of particular architectural, environmental, historic or artistic relevance’. As Adalberto del Bo of the Lombardy chapter of the Italian Order of Architects writes in an essay on the La Scala saga, ‘If this doesn’t qualify for a competition, for what other project does the Milan city council expect to propose one?’ Parmeggiani’s essentially conservative ‘definitive project’ was approved by the city council two years ago.

The works contract was won by CCC, a firm based in Bologna. As required by Italian law, CCC appointed its own architect – Mario Botta – to draw up the working plans, or ‘executive project’. Botta’s name was apparently suggested by Italy’s extravagant junior minister for culture, Vittorio Sgarbi, who has since been relieved of his duties. And Botta obliged, as Sgarbi expected, by turning what was meant to be the most discrete of internal renovations into a chance to make his mark on one of the world’s most famous temples of culture, foisting a couple of aggressive and entirely unnecessary eruptions onto La Scala’s roof and revealing them to the public only after work had already started.

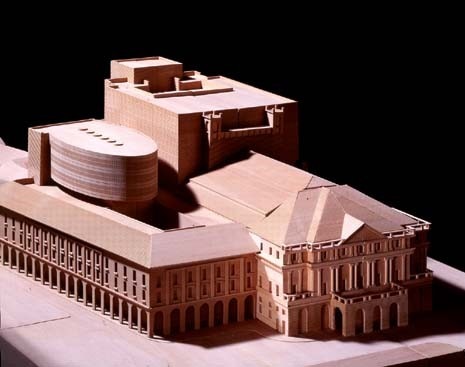

The law that governs this process states that these working plans are supposed to limit themselves to translating a finished project into an ‘engineerable form’. But Botta’s plan – nodded through without any formal city council approval in a way that a judge would later define dryly as ‘innovative’ – goes a lot further. The point was brought home in the course of a press visit to the La Scala site, where models of the Parmeggiani and Botta projects were placed side by side with a model of the existing structure. On the outside, Parmeggiani differs from the original only in its large, flat roof extension with curved edges, invented to cover the extended backstage area and accommodate the new, state-of-the-art stage machinery.

Botta proposes a far more radical pair of roof structures: a large, almost cubic fly tower that rises immediately behind two 1930s water towers (retained on the insistence of the local architectural heritage department), and its smaller, elliptical cousin, which hovers over the 1920s extension of the opera house along Via Filodrammatici. From the air, this elliptical structure, which will house dressing rooms, rehearsal rooms and the costume department, looks worryingly like a torpedo, menacing central Milan’s narrow streets. The new structures will be rendered in botticino marble – notorious as the glaring white stone that has refused to age gracefully on the Vittorio Emanuele monument in Rome. But botticino comes in many forms; the plan is to use a pale honey-pink version for the La Scala extension.

A legal case brought against the Botta project by an Italian environmental lobbying group, Legambiente, was thrown out by the regional administrative tribunal on all points except one: the judges agreed that the Botta plan was essentially a new project, rather than the executive version of an existing plan, and, as such, should have been formally approved by the city council. Deputy mayor De Corato immediately announced that approval would soon be forthcoming; but in the meantime, work on the La Scala site, which began in April 2002 with the dismantling of the stage, would continue: ‘so far, all the work that has been carried out is in line with the fully approved Parmeggiani plan’. During a press visit to the site last month, De Corato, resplendent in a beige ‘Cantiere della Scala’ works jacket sponsored by one of the site contractors, estimated that work could happily go on until September 2003 before city council approval was required.

Asked about the difference between his plan and the Parmeggiani project, Botta says that he was asked to ‘modify the structures that emerge from the roof in order to give them a more striking image’. The final volumes, he claims, actually add up to 60 cubic metres less than those of the definitive project, and Botta is proud of the fact that his project will also return the roof of the Via Filodrammatici side of the building to its late-19th-century height. The underlying idea, says Botta, is to ‘recuperate the old parts of the building and complement them with a new part that is really new’. Quoting Karl Kraus, he reminds us that ‘even old Vienna was new once’.

Those attempting to follow the intricacies of the La Scala affair, however, would do well to bear in mind the words of W. H. Auden: ‘No good opera plot can be sensible, for people do not sing when they are feeling sensible’. And certainly there seems to be no sensible reason to submit this historic building to the Botta trademarks of simplified geometry and lateral stripes. La Scala is not in San Francisco, it is not being built ex novo and it is not intended to house a museum of modern art.