The Japanese worship the Louis Vuitton brand with almost religious fervour, so much so that when the company opened its largest outlet in the world in Tokyo at the end of the summer, the event was marked by the spectacle of a 1,400-person queue waiting to cross the threshold. This devotion helps to explain how, in a country still in the grip of its longest economic recession since the war, Louis Vuitton has managed to increase its sales by 16 per cent in the past year. It’s just as well, since Japan is an enormously important market, accounting for one-third of the company’s annual turnover.

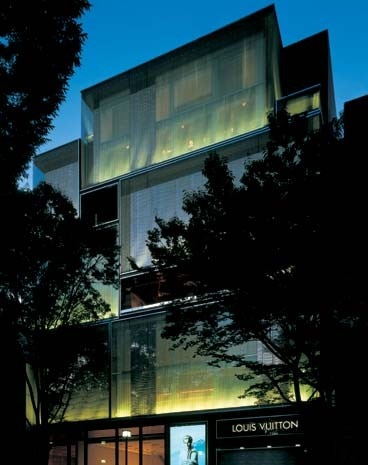

Jun Aoki’s five-storey building for Louis Vuitton is at the heart of Omotesando, which is rapidly turning into Tokyo’s version of Via Montenapoleone or Bond Street. Omotesando is a rarity in the Tokyo; built in tribute to the Champs Elysées, it is one of the city’s few tree-lined streets. It is also the setting for the pioneering Dojunkai social housing project, a landmark in the history of Japanese modernism, built in 1926 and based on Western precedents. Over the years the apartments have been taken over by artists, creative studios and idiosyncratic stores. The street is today at the centre of a significant transformation process that, in the space of a few years, will change its face, pushing out the remaining apartment buildings to make way for a growing cluster of fashion flagships.

Kengo Kuma, Kazuyo Sejima, Tadao Ando, Toyo Ito and Kisho Kurokawa are all busy designing here, working for Dior and Tod’s, among others. Paradoxically, the buildings of the fashion system may become the fixed points of Tokyo’s constantly fluctuating cityscape. Against a backdrop of constant evolution, where buildings have a very short life, partly due to alternating fortunes and fluctuating property values, Jun Aoki expresses very clearly that the contradictory relationship with context offers few guarantees of permanence. Aoki reconciles this with the need to construct an independent expression for the Luis Vuitton image. His building does not ignore the surroundings; in fact, it shows a high degree of adaptability to it, seeking a relationship with its context.

The dual skin of its surface, conceived as a fabric that envelops the structure of the building, is sometimes reflective and sometimes translucent. It blurs boundaries indiscriminately, conveying the signs of life that flow within it or reflections of the street and the foliage of tall trees: images in perpetual movement, glimpsed as if through a silk veil. The transparent facade and the textures of the light metal mesh render indistinct the divisions between interior and exterior, shop and street. Aoki does not ignore the presence of the Dojunkai housing directly opposite the store, even though it is due to be demolished to make way for a new project by Tadao Ando. Aoki claims that he was inspired by its architecture and acknowledges its power in having influenced the character of the area and its transformation over the years.

Reconciling fashion’s need for an identity with autonomous architecture, Aoki has, in the idea of ‘piling up trunks’, found the image that will represent the Vuitton brand and, at the same time, translate the exuberance of fashion to the scale of architecture. In the service of fashion, architecture risks being reduced to a particularly sophisticated form of packaging. Aoki might have attempted to exploit this metaphor to reconcile the exterior (architecture reaching out to evanescence and ambiguity of perception) with the interior.

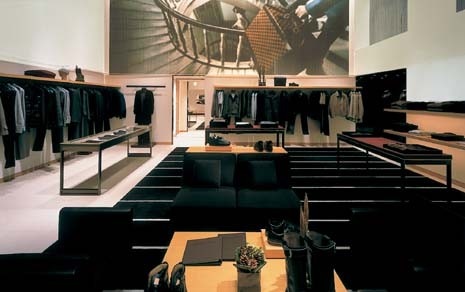

Instead he has opted for a very classical resonance (the refined boiserie along the walls alludes to the Parisian interiors of the original Vuitton building) and, albeit updated, respects Peter Marino’s interior design of the 1990s, which gives a consistent character to each of the 300 Louis Vuitton shops around the world. The pile of trunks pays homage to the origins of the store, founded in the great age of travel. Louis Vuitton was famous for inventing light trunks, whose poplar wood construction immediately rendered cumbersome luggage obsolete – no longer suited to new means of transport like transatlantic liners or the Orient Express. The pile of volumes, each of different proportion and size, rises 30 metres from a square plan with 20-metre sides, overlooking the avenue flanked by large zelkova trees.

The gradual upward composition of single volumes has allowed Aoki to proceed with great freedom in defining internal circulation routes, avoiding a schematic plan that proceeds by the superimposition of standard floors. Instead, the spaces (contained inside the single volumes) flow into one another, giving the impression of walking inside boxes embellished with a wooden covering or decorated weaves: padded places where the hierarchies between floor, walls and ceiling are lost, as in the large white hall that crowns the building, interwoven in an evanescent embroidery that seems worked in ice. In the face of architectural fact, the trunk image fades into allusion.

The dual skin wall system (metal weave on the outside, reflecting or glazed walls on the inside) seems to immerse them in a mist, dissolving physical substance. This is an effect made all the more theatrical by lighting placed between the two skins. The dual skin therefore serves a function: it leaves the doubt of an indistinct vision that strays into dream or mirage. In it are woven the reflections of the mirror panels turned shades of gold and pink, dematerializing the metallic effect of the steel mesh. ‘It was our intention to create a new material combining two different materials with a new spirit’, explains Aoki. ‘To do this, we designed four types of metal mesh with different weaves in detail. What we came up with was moiré. When two intricate patterns overlap, a third emerges. The third pattern has non-substance. It can be seen but isn’t there’. The different weaves of the metal fabric combined with the three types of rear panel (glass, steel polished to a mirror shine and gilded steel) made it possible to adopt nine different combinations to modulate visual effect and control variations in the composition. ‘The perception changes depending on the point from which the building is viewed – from below, “squashed”, from the bottom or from the other side of the street’