Raimund Abraham is one in a long succession of Austrian émigrés who have revealed the darker, more astringent side of European culture to America. The tapered tower he designed ten years ago for the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York is finally up and running. Its tiny but prominent site is in the heart of Manhattan, a block south of MoMA and the American Museum of Folk Art, on the same street as Saarinen’s CBS and Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building. In sharp contrast to these rectilinear icons and their debased progeny, Abraham’s tower is a knife slicing through the blocks of dough that flank it. It’s a slap in the face of reaction, political and aesthetic, and may yet prove to be a catalyst for New York and its exposure to the architecture of the avant-garde.

The Forum was originally based in a five-storey town house that it acquired in 1958. But the organization quickly outgrew it, and after considerable discussion the Austrian government decided use the site for a new structure that took fuller advantage of the zoning limits to go much higher, although still restricted to a site less than eight metres wide and just twenty-five deep. Kenneth Frampton, Richard Meier, and Charles Gwathmey were on the jury that picked Abraham’s submission over 225 other entries in a competition restricted to Austrian-born architects. The vestigial site and the city’s restrictive building code shaped his design, which turned these constraints to advantage. To provide the two escape routes required by the fire department, Abraham placed scissor stairs at the rear of the building to free up the rest of the floor plate; he poetically describes these intersecting staircases as ‘striving for infinity like Brancusi’s endless column’.

He conceived a threefold division between Vertebra (the stairs), Core (the 20-storey tower) and Mask (the stepped curtain wall of the facade). From the street, the building appears to be as exaggeratedly thin and angular as one of the towers shoehorned into Tokyo during the bubble years of the 1980s. But those pretentious edifices were designed for show, like vertical billboards, whereas Abraham’s is rigorous, lucid and surprisingly respectful of the urban grain. The wide facades of the hotel and office to either side are partially set back from the building line, allowing the Forum to step forward at its base and lean back 86 metres to fit within the zoning envelope. Zinc panels clad the concrete sides and the stair wall, with its diagonal slit openings.

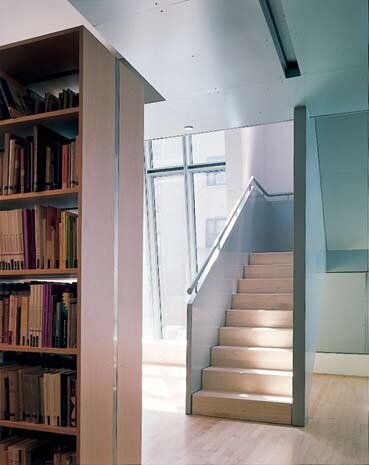

The cascade of tinted glass down the facade jogs inward twice at the halfway point, and this rhythmic punctuation is complemented by vertical elements and sharp-etched openings, all of which have useful roles to play besides relating the tower to its orthogonal context. The Forum’s needs were typical of cultural institutes: versatile exhibition and performance spaces; rooms for classes, meetings and seminars; a library; offices; and an apartment for the director. However, the verticality of the structure and the focus on experimentation challenged Abraham to create an interior that is transparent and permeable. An expanse of glass opens the lobby and its stainless steel half-cylinder service core to the street. A second-floor skylight illuminates the rear of the lobby, the split-level galleries below and the gathering places above while also revealing the rear facade of the tower. Flying stairs connect these floating platforms and lead up to an intimate two-level theatre that can be naturally lit by folding back wooden screens.

Light itself becomes the guiding factor in a visit to this building. You enter from the light of outdoors and move toward light filtering from the north facade at the back. Because of this arrangement of space and structure, visitors can visualize the entire experience from the moment they enter the building; the path is dictated by the stair and the flow of space. The building tells you where to go. Understanding that widely separated floors are only seconds apart by elevator and that visitor numbers are small, Abraham has interspersed public and private spaces. The double-height library above the theatre has a stair linking the book stacks to the mezzanine reading room. There are loft-like studios on levels six and eleven, one with bleachers set against the windows and the steel tubes that cross-brace the concrete frame, and staff offices in between. The director’s apartment is entered through the 19th-floor dining room, with an elegant maple stair spiralling down to the living room, master bedroom and children’s rooms. Below the peak of the tower, which shields the water tank and mechanical equipment, is a partially enclosed terrace for receptions that commands views down 52nd Street to the East and Hudson Rivers. For director Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, a diplomat turned cultural impresario, the Forum’s role is to foster collaboration between the United States, Austria and its neighbours in the arts of a new century.

He recalls how Vienna was the hub of a multinational avant-garde a century ago: the city where Freud and Schoenberg, Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos laid the foundations of modernity. After the First World War, Austria lost its empire, turned inward, enthusiastically embraced Nazism and destroyed its Jewish culture. Chastened by defeat and isolation, this small state has nurtured a new generation of creative artists, and the Forum can showcase their work and enlighten a city where high rents have banished the cutting edge to the outer boroughs. The recent opening of the Neue Galerie, a jewel-box museum for the arts of early-20th-century Vienna on New York’s Upper East Side, has relieved the Forum of its responsibility to deal with the pioneers, and now it concentrates on exploring the present and the future. An ambitious programme is planned that leaps over traditional boundaries, exploits the electronic revolution and takes modernism as its point of departure.

Time Space Existence: the Future of Architecture In Venice

Until November 23, 2025, Venice is the global hub for architectural discussion with "Time Space Existence." This biennial exhibition, spearheaded by the European Cultural Centre, features projects from 52 countries, all focused on "Repairing, Regenerating, and Reusing" for a more sustainable future.