The last time I heard Leon Krier's name mentioned was when Frank Gehry told me that he kept getting letters from him. It was a bit of a surprise, partly because you wouldn't automatically have concluded that Gehry was a Krier's kind of architect. But more than that, it reminded you of just how comprehensively Krier has vanished from the architectural world.

Before that, several years before in fact, there had been a bit of a fuss in Britain over Poundbury, the new town that he had planned for the Prince of Wales. Krier, it was rumoured, was unhappy at the way that what he had seen as a chance to realise his dream of building an ideal contemporary city rooted in the traditional values of urbanism was being dilluted into a Potemkin village. He wanted to quit, but the courtiers around the prince wouldn't let him. It wasn't so much the establishment pressure not to rock the boat that kept Krier quiet. How could he simply abandon the project, it would be just too embarrassing? Here was a one time Marxist, author of a sympathetic study of Albert Speer's architecture in which he deplored the logic of a world that insisted on demolishing Speer's street furniture in Berlin, but refused to jail Werner von Braun, a polemicist who had inscribed the words A Mon Prince on the title page of one of his books, now confronted with the realities of life at court.

There was simply nowhere else left to go. So Krier did not resign. Instead, he simply vanished off the architectural radar screens. There was complete silence; punctuated only by occaisional reports of sitings of the missing architect from France, where Krier was said to be living quietly with his piano. Even when Richard Ingersoll wrote an engaging lament in the pages of Architecture America recently, under the title, "Are you now, or were you ever a post modernist"? Krier's name signally failed to come up. It is a surprising outcome for an architect who even now is still only in his middle 50s, who did far more than just show early promise, and who has no embarrassingly dated built works hanging like millstones around his neck. For two decades and in many different incarnations, he was an architect who brought a remarkable sense of moral authority to everything he did. From his brilliant gift for pamphleteering, to the haunting beauty of the imagery of his drawings.

He had a talent for being in the right place at the right time. After he left his native Luxembourg, Krier was in James Stirling's office in London at a critical moment, coinciding with Stirling's move away from the glass and steel of Leicester and Cambridge, to the stone faced monumentalism of his mid period. Krier's spidery ink drawings delineated a series of Stirling's most important projects, and helped to give them their power, a Gandy to Stirling's Soane. In some cases, it was more than that. It was Krier who had the idea of utilising the facade of the assembly rooms in Derby as a fragment wrapped in Stirling's glass collonade.

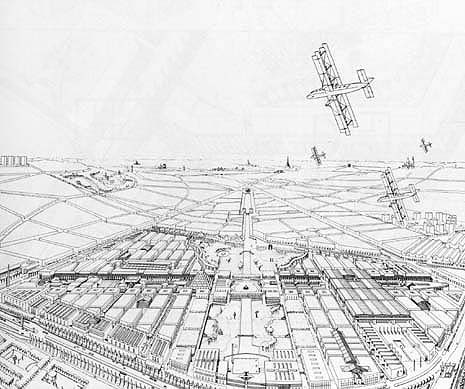

Krier's unmistakable drawings populated by curiously displaced technological anachronisms, the biplane over contemporary Luxemborg, the pre war cars in Post War Berlin, the teasing Schinkel like 19th century figures, Stirling's own bulky figure seated in one of his own Thomas Hope armchairs changed the way a generation drew, and thought. They were atmospheric images that hinted at an architectural world of a sophistication that in the bleak 1970s seemed to be entirely beyond reach.

There was a break with Stirling, quickly followed by disillusionment with the idea of architectural modernism, and then the modern world altogether. Krier was to become a militant fundamentalist, of a kind that Pugin would have recognised, the fiercest critic of the architectural profession, and its -as he saw it - shameful, treasonable collaboration with the destruction of the traditional european city, a tragic act amounting to the extinction of mankind's greatest creation. But not before he had tutored Zaha Hadid at the Architectural Association, leaving a lasting impression on the most charismatic of the new generation.

And then there was his involvement with the new urbanism, the creation of Seaside, the Florida holiday village with its collection of well mannered architect designed houses, where Krier got to build something with his own name on it, no matter how modest, but also to define a set of city rules that seemed briefly like a panacea to save urbanism and were to spawn a whole series of imitations.

Then there was nothing. The worrying prospect for architecture is that in the storm of computer generated virtuality, and toughest kid on the block neo brutalism, and architects hypnotised by the Apocalypse Wow spectacle of exploding Pacific Rim cities, Krier, by dissappearing is once more in the right place at the right time. And if he is right, it raises the intriguing question of what will happen if and when he resurfaces.

The Mirra 2 combines ergonomics and sustainability

Redesigned by Berlin-based Studio 7.5, the Mirra 2 chair from Herman Miller represents the perfect combination of function and innovation.