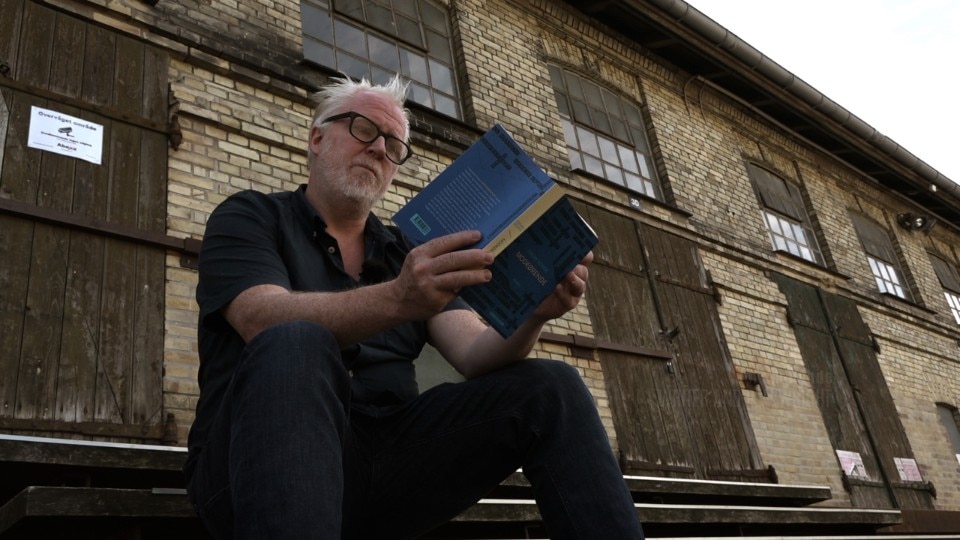

Despite its reputation as the most livable city in the world, Copenhagen is also a place full of contradictions and economic disparity. To this inherent ambivalence is dedicated director Hans Christian Post’s fifth documentary, which evocatively portrays the two faces of the Danish capital. Titled Best in the World, the feature film, in fact, offers a revealing look beyond the postcard image of the metropolis. “Although Copenhagen has acquired some great qualities over the years, it has simultaneously become an engine of inequality both within its borders and in the surrounding countryside,” the director explains. “I have personally experienced over the years all the behind-the-scenes of the transformation: the gentrification that ensued, the people who were driven out of the city to make room, the interesting neighborhoods that were destroyed along the way.”

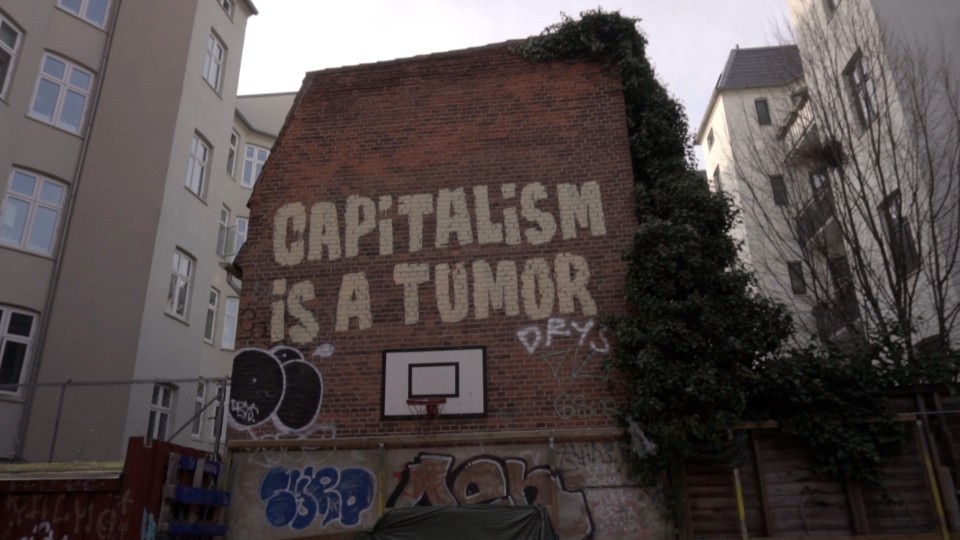

If a city is not for everyone, but only for a small population segment, it cannot be considered a model for the future.

Hans Christian Post

But the Danish capital’s identity was not always what we know now. Only in the 1970s was Copenhagen an industrial city, poor and on the verge of bankruptcy. Thirty years of careful political and architectural planning have since made it the city immortalized in Post’s sequences: from above portrayed as orderly, imposing, and elegant, while the camera shoots frontally only what is bare, desolate, or sadly still under construction.

“The world’s best city agenda comes from lifestyle magazines that specifically target expatriates and foreign companies looking for attractive cities in which to live and work or in which to start a business. Locals are not the target group they are referring to,” Post continues. “Copenhagen certainly has some very nice features in terms of infrastructure, between bike paths, great parks, and squares, which are certainly great urban qualities. But a city is only truly great when socially and culturally diverse, preserving a balanced relationship with the surrounding regions. If a city is not for everyone, but only for a small population segment, it cannot be considered a model for the future.”

“This is why I wanted to portray the background of Copenhagen’s transformation: where do we want success to take us? In the case of Copenhagen, the goal in the 1990s was to attract a wealthier population. But there is always more wealth to attract, and this strategy could lead to the current population moving away and the city being taken over by even wealthier people or pension funds.” The reading that follows from the documentary is that of a city in danger of becoming a victim of its own success.

The documentary alternates between many different voices and perspectives, which are useful in getting a complete and diverse picture of Copenhagen’s transformations, and the benefits and costs involved. Architects were given the role of proposing practical solutions to the residential problem. “In my opinion, designers’ initiatives hardly go well. Although they are increasingly aware of the social aspects of construction, architects have no solution to break the economic spell. We need to look hard at the different economic patterns underlying the urban planning we see in our cities, and perhaps economists could have provided some interesting insights in this regard.”

Here is the voice of Frederik Noltenius Busck, leading the CPH Village I project, an ambitious student housing project built through unused shipping containers led by the slogan “Live small-scaled, but well. And rather with fewer private square meters, and more common square meters.” But even in this idea, there remains a class divide regarding public and shared spaces. “The wealthier classes often have the means and power to define how and when public spaces should be used and by whom,” the documentarian concludes. “Architects and legislators should therefore ensure that public spaces are designed for everyone and have a broad and very flexible program.”