Andrejs Legzdiņš was born on 11 January 1936 in Riga, Latvia. Because of the Second Soviet occupation of his country, he was forced to emigrate to Gottland, Sweden, when he was only eight years old. He moved there with his family after a tormented journey at sea on a fishing boat overloaded with migrants. At the age of thirteen, he discovered a passion for architecture thanks to his father, who was also an architect. After finishing school, he enrolled in a course in Art Krafts and Design at Konstfack University in Stockholm, where he graduated as an interior architect and furniture designer. In 1953, while he was still a student, he started working as an apprentice in the studio of David Helldén – a Swedish architect famous for having contributed to the redevelopment of the city of Stockholm and for having designed the new Malmö Music Theatre (1933-44) together with Lallertstedt and Sigurd Lewerentz. In the studio, Andrejs was responsible for creating the models: by working with cardboard, he could give a spatial sense to the design and imagine different perspectives. After graduating, he continued to work for David Helldén until 1974, when he became a partner in another studio until 1988. Also, in 1974 he began teaching Interior Architecture and Furniture Design at Konstfack University (until 1993), and in 1995 he became professor of design at the Mechanical Engineering course at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, where he continued to work until 2006.

“Doing more with less could be a great way to describe my work”, Andrejs Legzdiņš tells Domus while quoting legendary Richard Buckminster Fuller, whose philosophy is one of the founding principles of his architecture. The Latvian-Swedish architect, who was regularly published on Domus by Lisa Ponti during the 1970s, is now back to talk about his projects – almost forty years after being featured on the magazine for the last time.

In Domus, you published many projects of ante litteram circular design, sofas on wheels, and ultralight technological products. Can you tell us more about it?

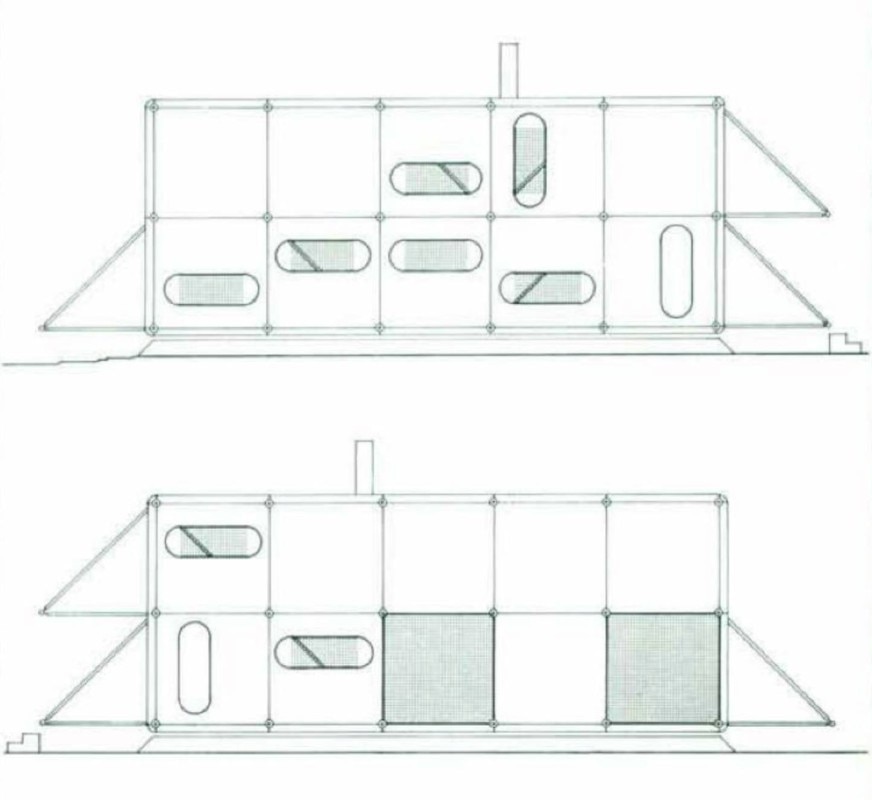

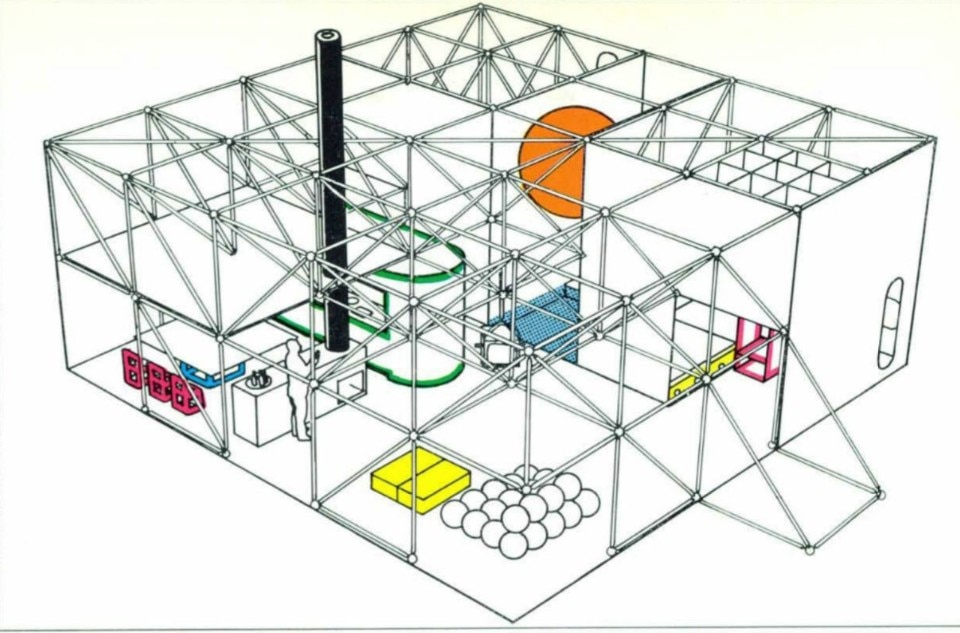

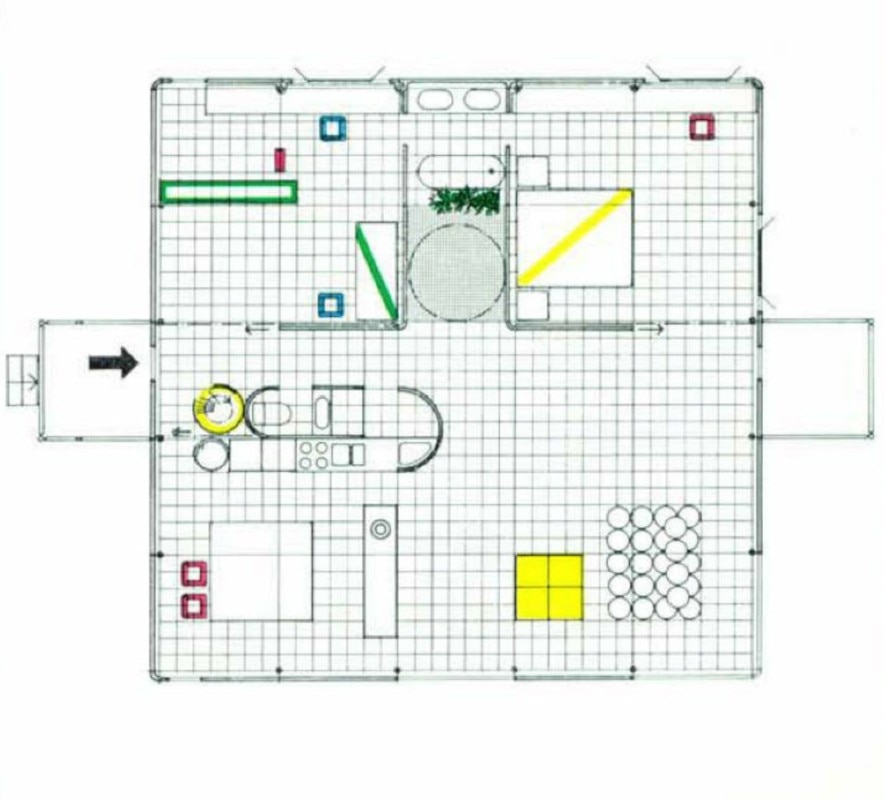

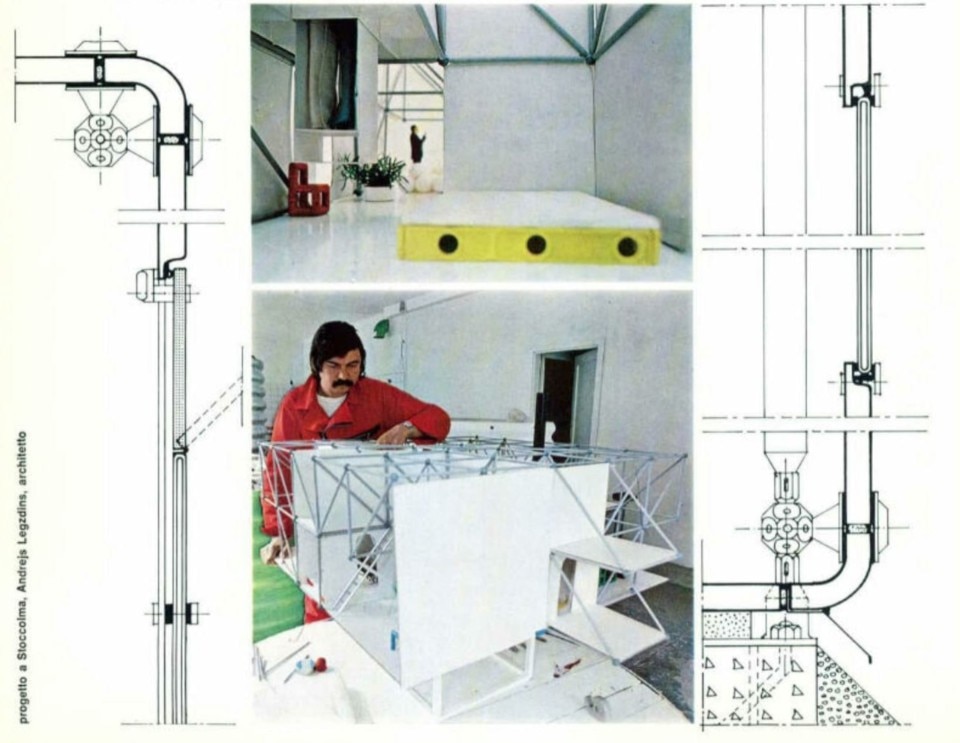

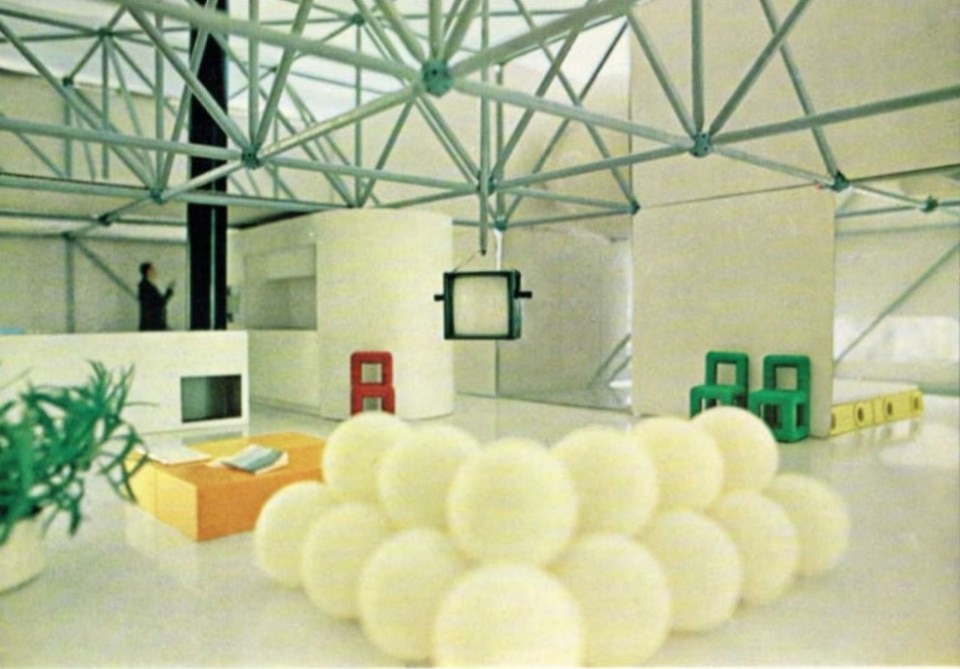

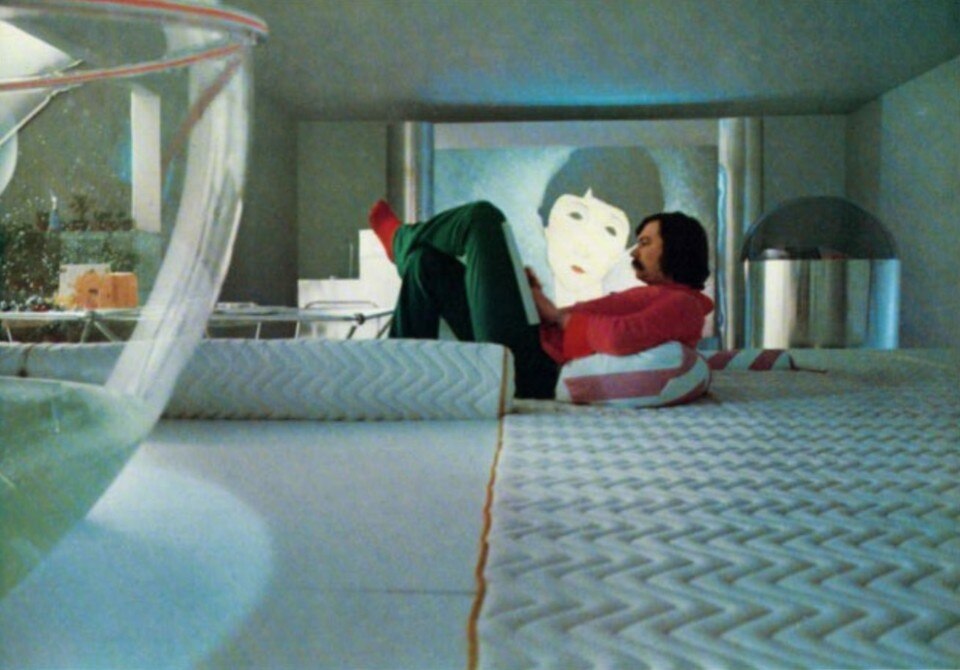

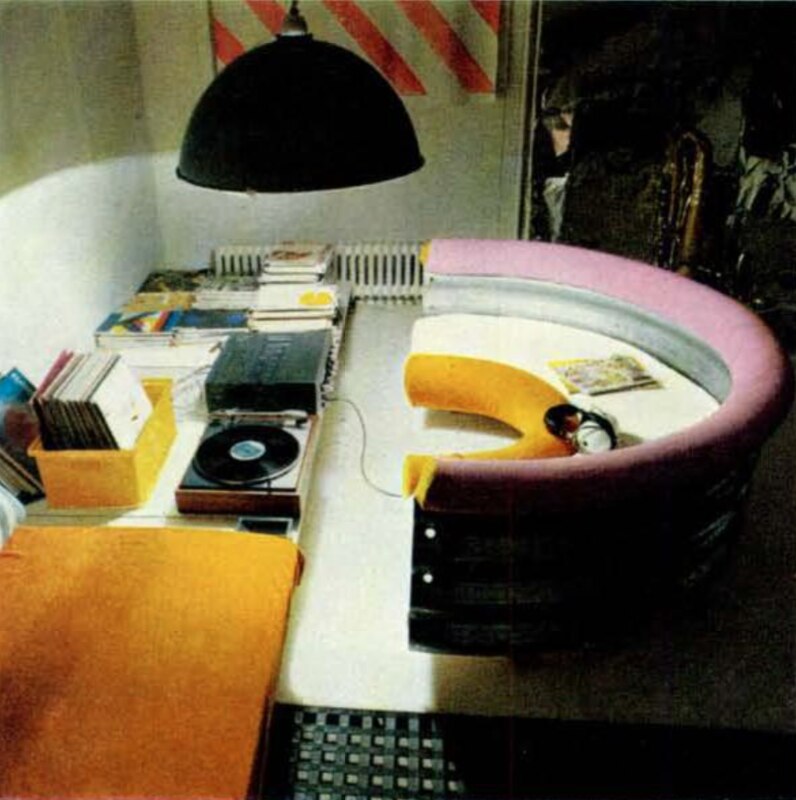

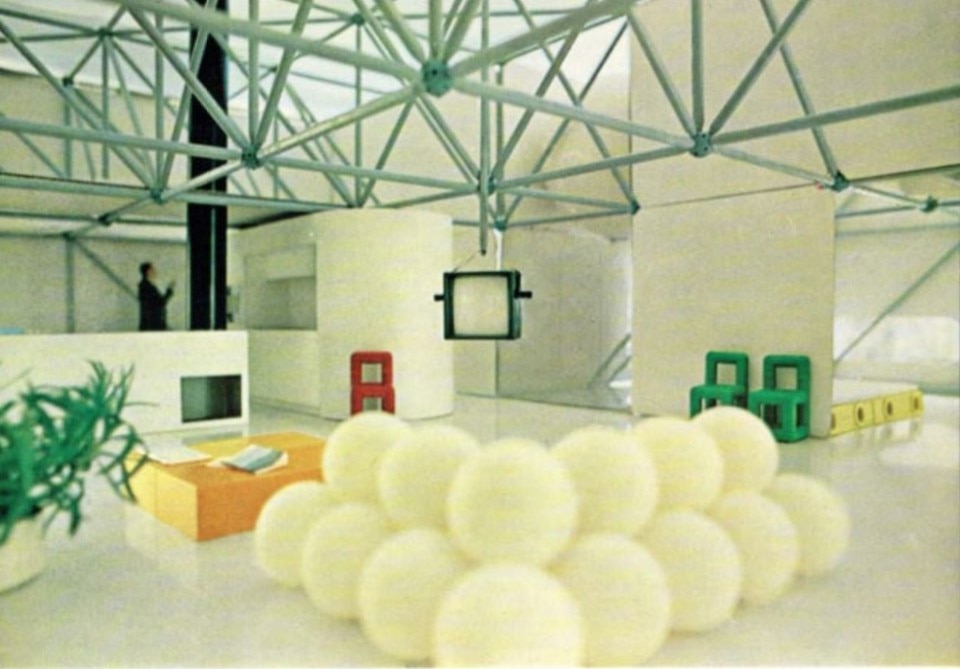

I started working with the magazine in 1972 when two housing units I designed were published in issues 508 and 509. The first project was the interior of our house, which was made from corrugated metal sheets that I had salvaged from an exhibition. With that material, I designed the sofas that moved on wheels (which were made of foam rubber and were covered in brightly coloured tricot), as well as the cylindrical walk-in wardrobe and the bar top. I used that material because at the time I didn’t have any money, and we were celebrating my grandmother’s 85th birthday and we needed the house to be ready for the party. The second one was a house whose structure was made entirely of steel tubes covered with fibreglass sandwich panels with insulating foam inside. Still on the subject of houses, in 1973, in issue 522 was published a “future house” – a house designed with a scenographic, utopian, and technological vision of what life would be like in 1997 (25 years later).

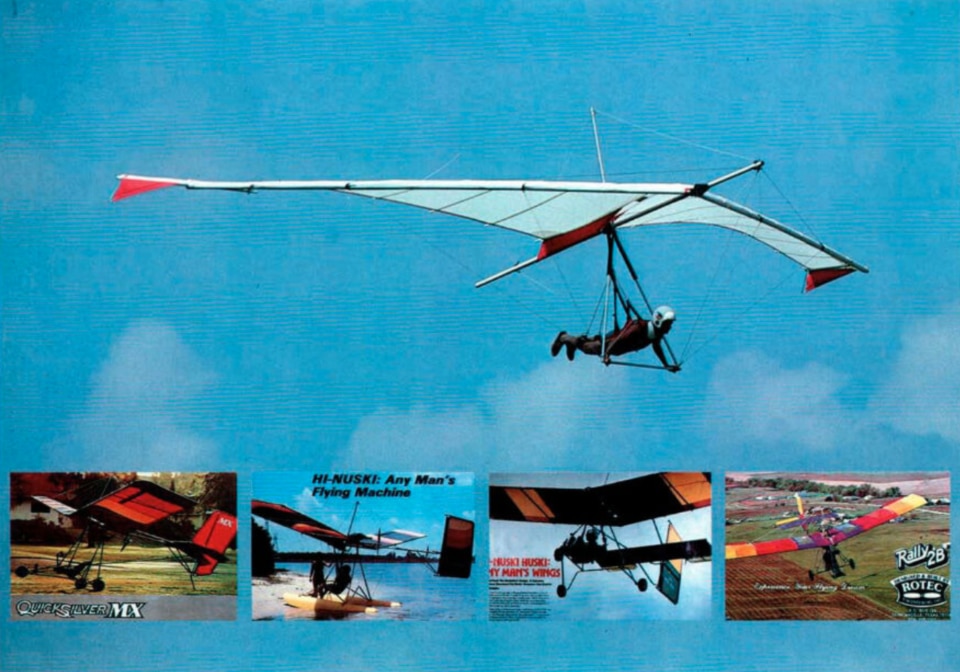

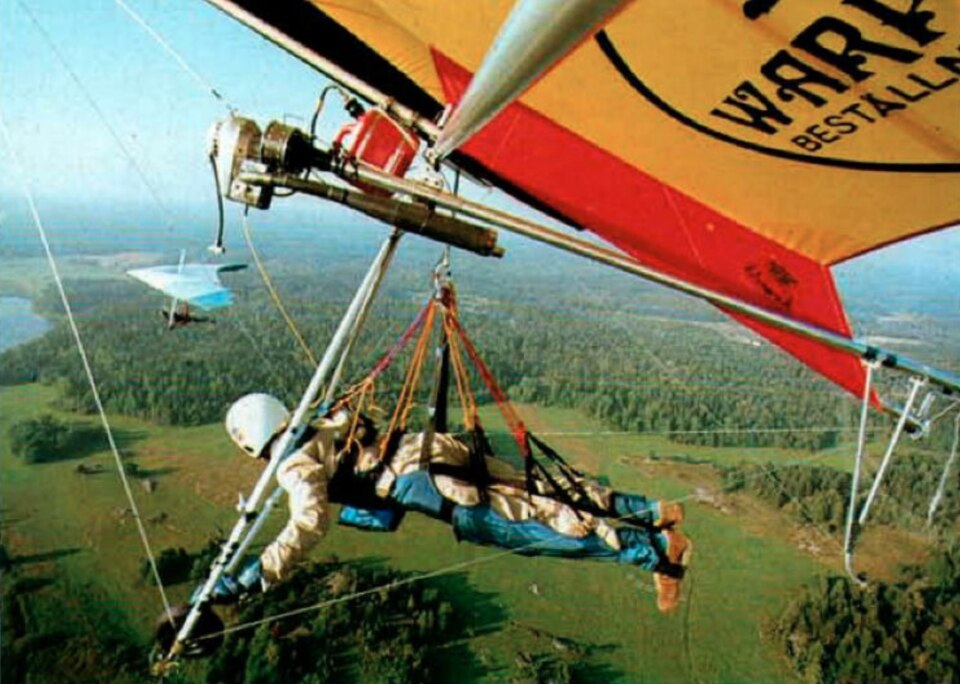

In 1982, Tommasi Trini published the sofa made from sheet metal in his article La chiocciola dei sensi which was published in Domus 624. It was a personal analysis by the critic about the last thirty years of interiors published in the magazine. I found myself among Elwood, Belgioioso, and Colombo, and I was delighted. Lisa Ponti had also agreed to publish some industrial design projects in Domus, as in the article ‘Ultralight Ideas’ published in issue 365, where I talked about light aircraft and how to use this concept on the ground, and humanise technology and make it serve humans (and not go against them).

What was your relationship with Lisa Ponti like?

I met Lisa Ponti a couple of times, the first time in Milan, in 1972, during the “EURODOMUS” exhibition. She was interested in setting up my “plastic house” project (no. 509, 1972) for the next exhibition, but it wasn’t possible because it wasn’t in production, and I didn’t have anyone to sponsor it. Then we met in 1973 at the Louvre in Paris to celebrate Domus’ 45th anniversary. On that occasion, he introduced me to Gio Ponti, who was surprised to hear my name, because it didn’t sound Swedish to him. I explained that I was born in Latvia and he told me that he had worked with some Latvian architects during those years.

I remember that one time in Paris, Lisa Ponti, Peter Cook, and I went around the city’s architecture schools together. We were annoyed by the fact that the 1968 revolution had caused the faculties to skip classes and the students were holding political meetings and showing very little interest in architecture. The same thing happened in Sweden: to be a radical student in design schools, you had to be a Marxist-Leninist or carry your red Mao booklet anywhere you went. I, on the other hand, was very keen on everything high-tech, so I completely devoted myself to my research. In 1972, we didn’t have the internet and to me, Domus was a platform to experiment, to meet with other professionals, to get information about what was happening at that time in the world of architecture, design, and art.

All the things we admire and find beautiful in nature serve a purpose and a function for the survival of the planet. Compared to man-made objects, nature has had millions of years to perfect its ‘objects’.

Research into domestic space is very important to you and your work. How did you imagine the “house of the future”?

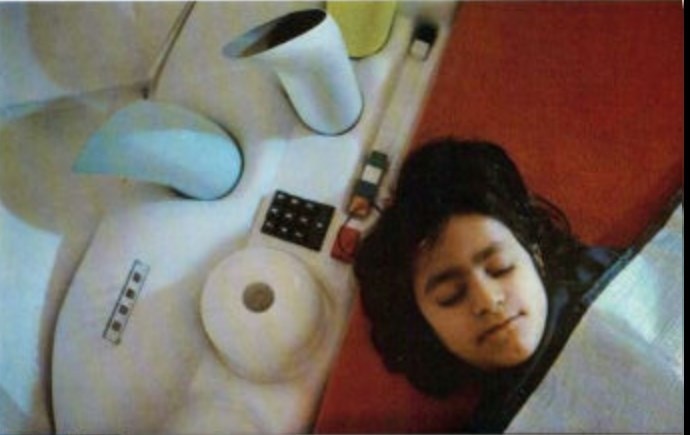

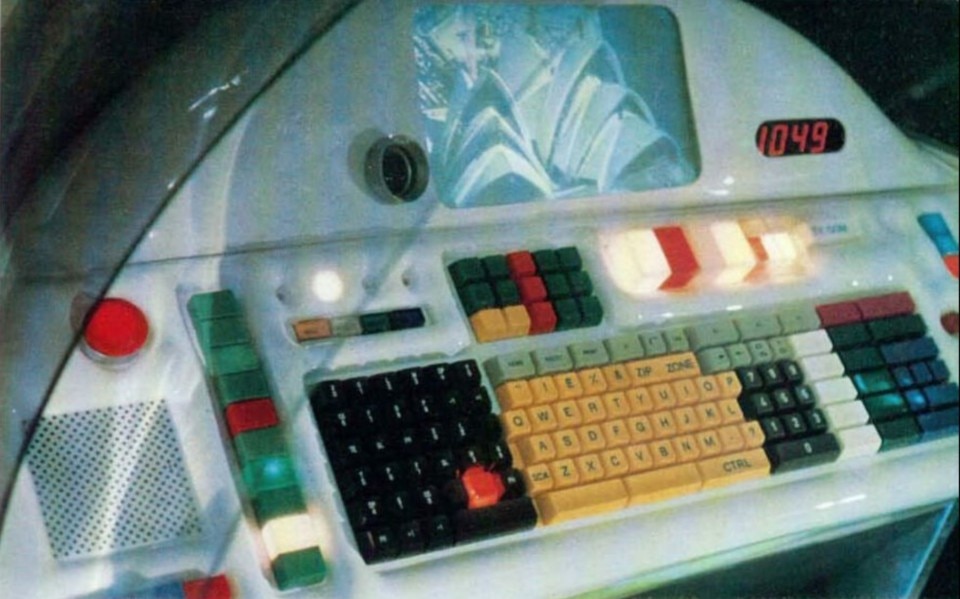

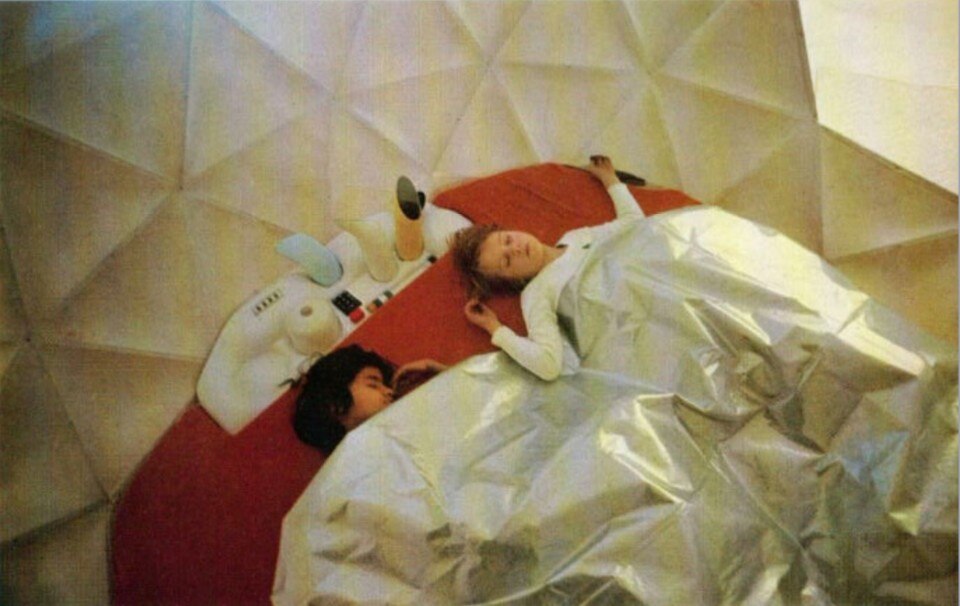

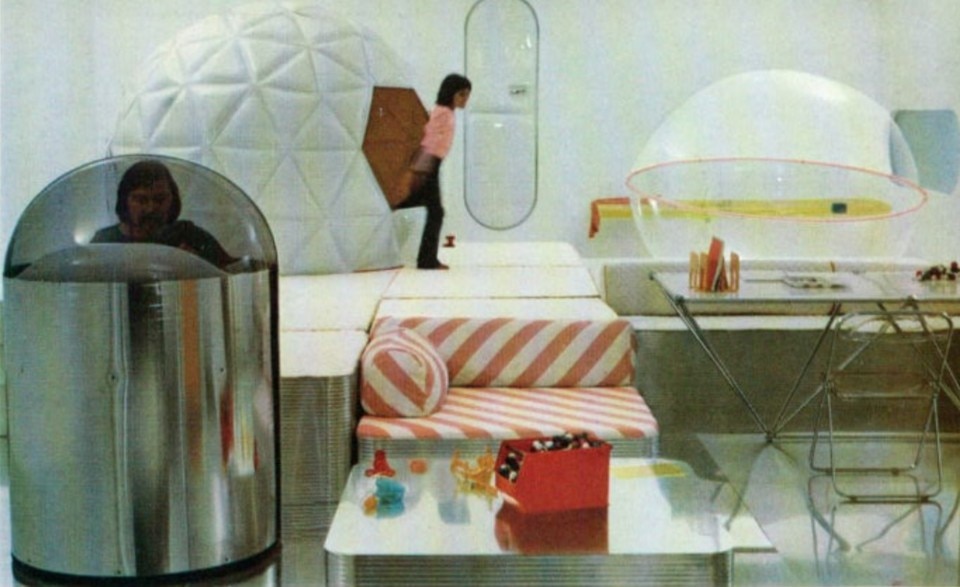

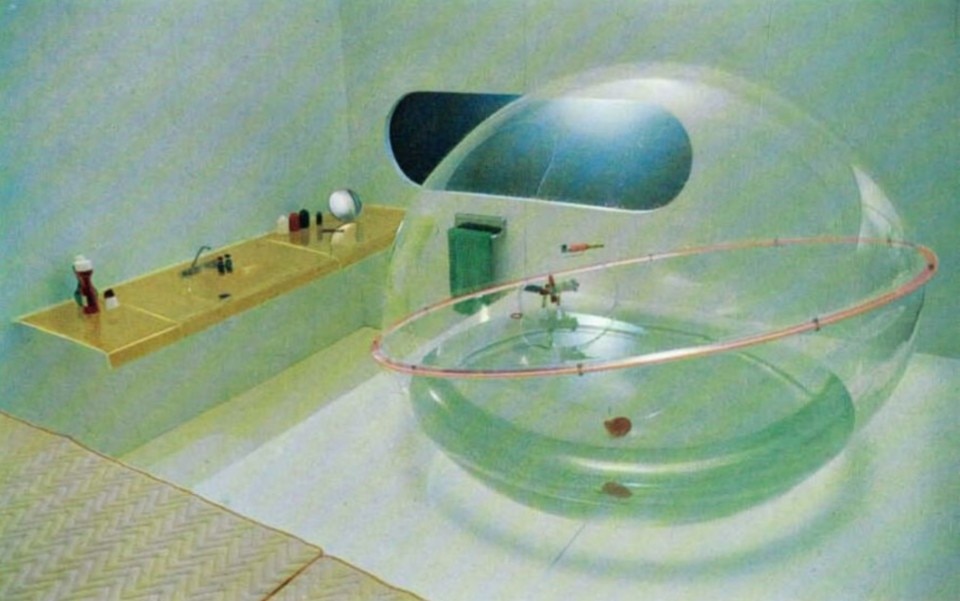

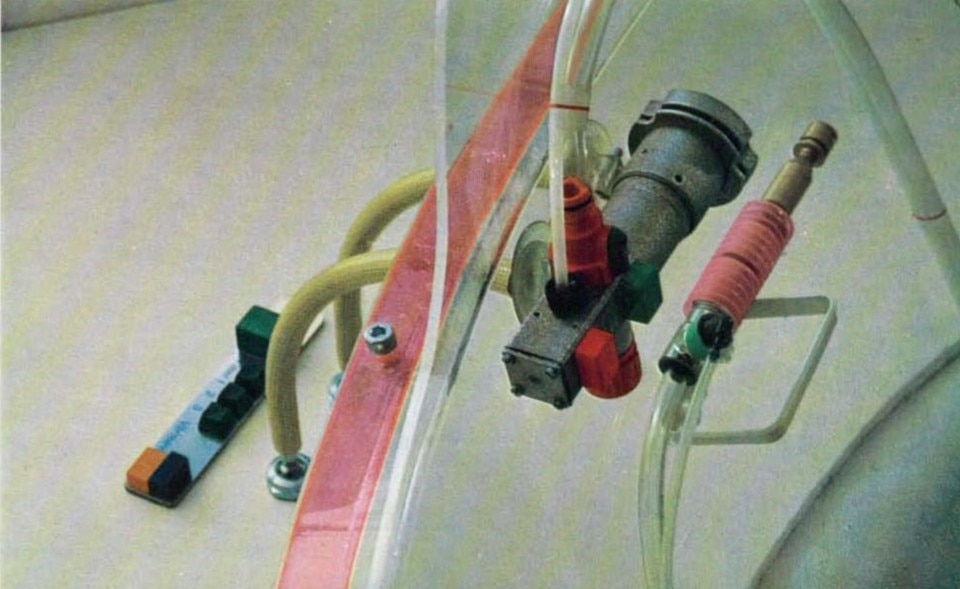

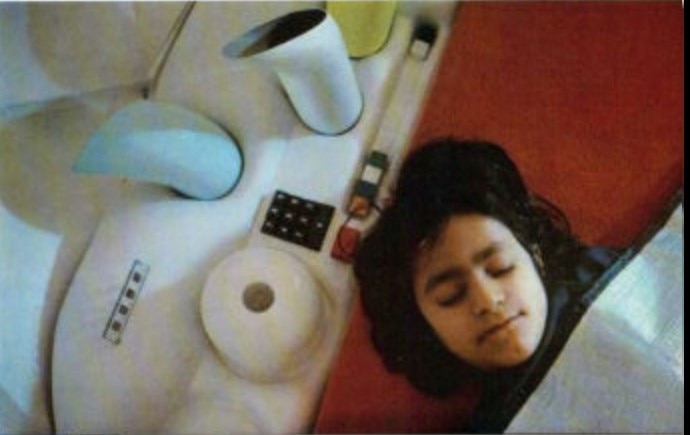

I did it in collaboration with photographer Hansa Hammarskiöld, and we started with the idea of imagining a house inhabited by a young family 25 years after 1972. At the time there were no computers and we came up with these playful devices arranged in a single room measuring 6x12 metres: the night-dome, with the thermal and light conditioning equipment, the transparent perspex bathroom-sphere with a diameter of 1.80 metres, a kitchen-table that entered the greenhouse where the family grew vegetables to eat, a cube-sink on wheels, a television screen on the wall that was as big as the wall itself, measuring 2x3 metres, and an electronic terminal to control all the devices in the house. We thought of and showed a new lifestyle and a new way of sleeping, cooking, bathing, relaxing, growing vegetables. Everything had to be sustainable, the water used in the bathroom was being recycled in the greenhouse and the dome where we slept had to control the temperature of the whole house. Finally, the “home terminal” contained the control keyboard for the audio-visual system, air conditioning, automatic watering of the greenhouse, and so on. It also had a video phone and was connected to libraries, film libraries, museums, information centres so that an exhibition or whatever could be shown on the big screen. It was a mobile device, it had wheels, and a blackout hood, which allowed you to isolate yourself when receiving “distant calls” with the video-telephone. The bathroom, in particular, was not just a place to wash but also a spiritual place to relax. To design it, I started from the theories of Fuller, who, to reduce water consumption in the Dymaxion Bathroom, had created a mist shower.

You talked about ecology and sustainability at a time when no one paid much attention to these issues. Today, on the contrary, they’re extremely topical…

All the things we admire and find beautiful in nature serve a purpose and a function for the survival of the planet. Compared to man-made objects, nature has had millions of years to perfect its ‘objects’. When I started designing ultralight aeroplanes, my goal was to find an absolute design that would look like a copy of a natural element. I designed a 70 kg object that anyone could build by themselves, with a 10-20 Hp engine. This project also referred to Fuller, in particular to the “Tensegrity” lightweight structural systems based exclusively on tension and compression, with minimal use of materials. In the article published in Domus 635 in 1973 in which I described these aircraft, I also explained my theories on the ecological and climatic issue. When we look at an F16 fighter plane we find it beautiful, but nobody designed it to be beautiful – it is a Computer-Aided Design (CAD) product designed to destroy and kill. Its shape resembles that of a shark, an animal created by nature that is also a perfect killer. In nature, we find the origin of everything. By studying nature, we can learn a lot about beauty, but also about technical solutions, efficiency, and the principle of Doing more with less.