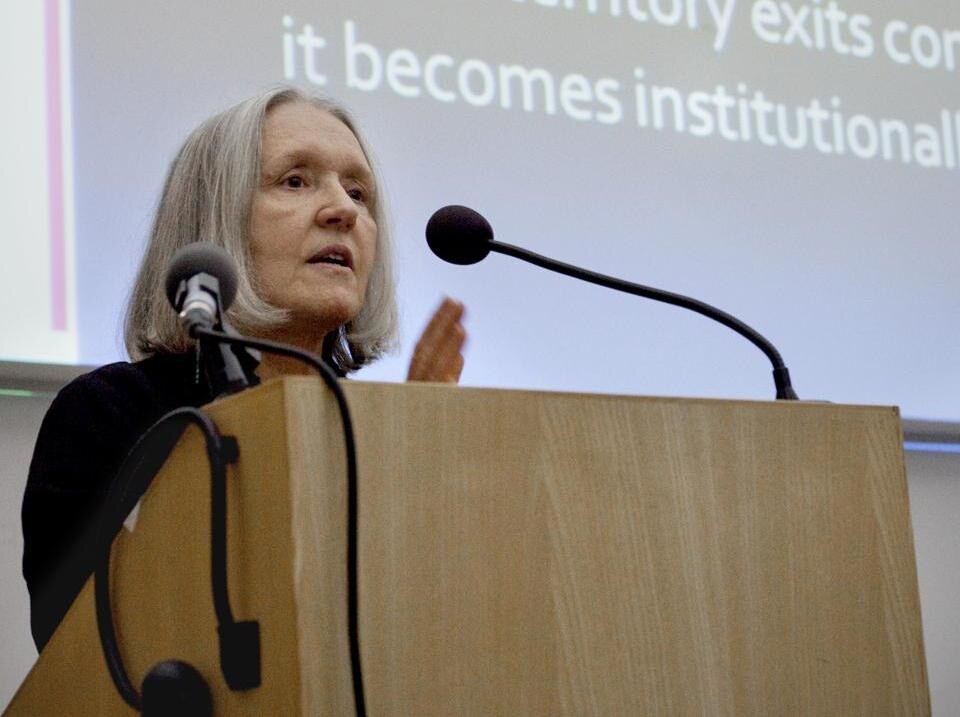

Sassen's lecture last month was entitled When the fundamental challenges of our time materialize in the city. In an overflowing lecture hall, she accompanied us on a journey through the different places and passages of her research on the "state of things" in urban and global sociology. In the aftermath of the events taking place around the world, this was an opportunity to explore her thinking on the growing political content of the actions undertaken in the urban space of global cities in relation to declining politics in the nation-state.

Saskia Sassen: Yes, that is how I see this shift, though from the beginning I have argued that the growing concentrations of capital power in global cities also brought with them added meaning to the struggles against gentrification, for the rights of immigrants, against police brutality. The local struggles taking place at the level of a block or a neighborhood or a square were in my view global struggles…the making of a globality constituted through very localized issues, fought locally, often understood locally but which recurred in all globalizing cities...Today's street struggles and demonstrations have a similar capacity to transform specific local grievances into a global political movement, no matter the sharp differences in each of these societies. All these struggles are about the profound social injustice in our societies—whether in Egypt, Syria or the US and Spain.

Yes I agree. To put it sharply and to the point...In each of these cases above and so many others, I would argue that the street, the urban street, as public space is to be differentiated from the classic European notion of the more ritualized spaces for public activity, with the piazza and the boulevard as the emblematic European forms. I think of the space of "the street," which of course includes squares and any available open space, as a rawer space where those without access to the instruments of power can make the political, make the social...The Street can, thus, be conceived as a space where new forms of the social and the political can be made, rather than a space for enacting ritualized routines. With some conceptual stretching, we might say that politically, "street and square" are marked differently from "boulevard and piazza": the first signals action and the second, rituals.

Today’s street struggles and demonstrations have a similar capacity to transform specific local grievances into a global political movement, no matter the sharp differences in each of these societies.

I could not comment on Southern Europe specifically, but I have seen this happen in many different places. Take New York, there are many small initiatives that might look silly to some coolheaded social scientist, but they amount to something...There are over 100 urban farms in New York City...these are mostly micro-interventions in urban space, more and more people are keen on "occupying" any plot of land with vegetables, plants. That is great. It is not enough but if we see a multiplications of these efforts across a broad range of substantive initiatives, we might arrive through a hundred small interventions to mobilize people, constituting a new type of civic spirit.

In many ways this would be one use that is an urbanizing of the technology. Do let me add immediately that it seems to me a common type of mistake of interpretation to conflation a technology's capacities with a massive on the ground process which used the technology. Thus, Facebook can be a factor in very diverse collective events—a flash mob, a friends' party, the uprising at Tahrir Square. But that is not the same as saying they all are achieved through Facebook. As we now know, if anything Al Jazeera was a more significant medium, and the network of mosques was the foundational communication network in the case of the Tahrir Square Friday mobilizations. In my research I have focused extensively on this issue, this confusion (Sassen, Territorio, Autorità, Diritti, Mondadori, 2009; Latham and Sassen, Digital Formations, Princeton University Press, 2005). The conflation I refer to above, results from a confusion between the logics of the technology as designed by the engineer and the logics of the users. The two are not one and the same. The technical properties of electronic interactive domains deliver their utility through complex ecologies that include a) non-technological variables—the social, the subjective, the political, material topographies—and b) the particular cultures of use of different actors.

Yes, I think your list of cases and examples is good...it gets at some of this. But I think in my own research I am more interested in developing/discovering that in-between space, and yes, you said it right that incompleteness and indeterminacy of the city. It will take practical and technical knowledge and it will take art!

Saskia Sassen is professor of sociology at Columbia University in New York and co-director of its Committee on Global Thought.