After a decade of idleness and despite widespread opposition, the Atatürk Cultural Centre (AKM, by its Turkish initials), in Istanbul’s Taksim square, was torn down last year. With its bold curtain-wall façade, the AKM was an icon of Turkish high-modernism, representing the secular, modern values of the westward-looking Republic in the heart of the city. Meanwhile, an imposing mosque is rapidly taking shape at the other end of the shapeless square: the concretization of a hotly debated project dating back to the 50s, marking the Islamization of a place that has for a century constituted the quintessential space of modernity in the city.

This ongoing radical transformation needs to be assessed in historical perspective. Located in a non-Turkish majority area on the city’s margins, upon the foundation of the Republic Taksim was chosen as the new civic centre, far away from the historical peninsula filled with Ottoman monuments and Byzantine remnants. This way the newborn State appropriated and Turkified a mainly non-muslim space, while also distancing itself from a burdensome urban legacy. Since then, Taksim has always been a highly charged space where subsequent governments and administrations scrambled to leave their mark, or to erase the traces of predecessors.

“Who takes Taksim takes everything”: thus professor Birge Yıldırım, who has researched and written extensively on the topic, sums things up. The square’s symbolic significance, coupled with a planning culture of highly politicized, piecemeal urbanism, she explains, generated a continuous process of addition and subtraction which turned Taksim into an architectural battleground, reflecting the political, ideological, and cultural faultlines transecting Turkish society. This resulted in the square’s indefinite layout and unresolved character.

With its multilayered nature, the site of Gezi park well exemplifies this confrontational approach to urban transformation. The ‘Promenade park’ was built in the 40s as a stage for modern life, following French planner Henri Prost’s project, razing down the Ottoman Artillery Barracks. Istanbul’s mayor at the time proceeded to demolish the building from behind, without informing the government.

As the base for an ‘anti-Western’ riot staged in 1909 by conservative officials opposing the Young Turks reforms and supporting Sultan Abdulhamid II, the barracks carry a specific significance in the Islamist political imaginary (1). Their controversial reconstruction as a privatized shopping mall, envisioned by the AKP administration, amounts to an architectural manifesto of Erdoğan’s “Turkish model” – a blend of neoliberal economics, social conservatism and authoritarian democracy.

Not incidentally, it is in Gezi that this model shattered, as the 2013 riots ignited by the project and the government’s reaction marked the shift from soft to hard totalitarianism in the country (2). During the occupation of the park, the AKM became a palimpsest for oppositional banners and protest messages; and the Turkish president announced its demolition by acrimoniously addressing its opponents: “Rant and rave, we destroyed it”.

Yet Gezi park, just as the barracks before, are built on an old Armenian cemetery: the park’s marble steps are said to be gravestones.

The barracks plan has momentarily been shelved, but the square pedestrianization has been hastily carried out, with the construction of a traffic underpass, a solution interpreted by Yıldırım as a spatial tactic to easily block pedestrian access to Taksim, if need be.

As a central space imbued with the symbolism of state authority, indeed, Taksim has always been also the stage for counter-representations and confrontational demands, such as the banned May 1st demonstrations, Armenian genocide commemorations, and violently repressed Pride parades. Beyond state attempts to impose top-down narratives, the square maintained its character as a heterogeneous public space: “No square is more public than Taksim in the country”, as remarked by Imre Azem, director of documentary Ekümenopolis, focusing on Istanbul’s urban transformation.

Now, the government is deploying a variegated arsenal of interventions to assert its control over it: from heavy patrolling to propagandist photographic exhibitions, from Ramadan dinner services to government-sponsored festivals such as the so-called “Democracy Festival” – staged in the square after the failed 15th July coup, when the AKM was covered in a gigantic red banner reading “Sovereignty belongs to the people”.

This dramatic and deliberately choreographed restructuring carried out by the AKP government is, however, all but an exception to Taksim’s century-long eventful history: a form of ideological urbanism, unilaterally intervening on a space laden with multiple, conflicting meanings. Ekrem Imamoğlu, Istanbul’s newly elected mayor from the opposition, announced a new competition to reshape Taksim square only ten days after his election, with the aim to “turn Taksim into a place everyone will be able to enjoy” (3). It seems indeed that in the years to come Taksim will maintain its character as a contested public space constantly in the making.

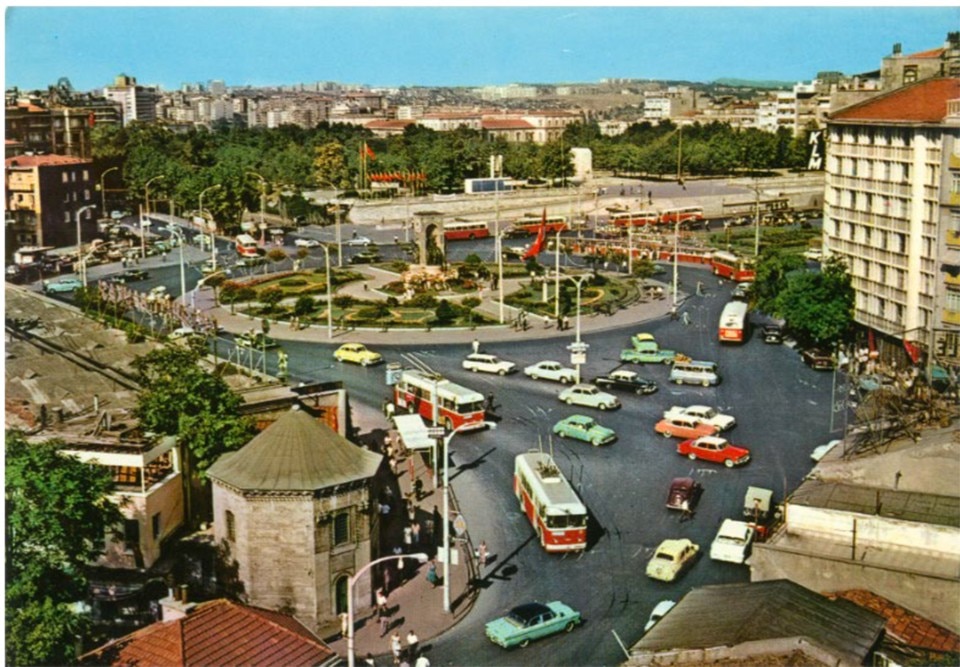

Opening image: Taksim, ca. 1936. The Artillery Barracks have not yet been demolished; in front of them, the horse barn has been remodeled to t the round square, centred on the Republic monument. On the left, Talimhane – the military parade ground – is being lled up with construction. Courtesy of SALT Research Archive

Francesco Pasta is an architect and researcher based between Rome and Istanbul. His research interests and practice are centred on people-driven urbanism, participatory design methodologies and collaborative planning, urban citizenship and spatial politics.

- 1:

- Hafıza Merkezı: Hatirlayan sehir: Taksim’den Sultanahmet’e Mekan ve Hafıza [The Centre for Memory: A city that remembers: place and memory from Taksim to Sultanahmet.]

- 2:

- Cihan Tuğal: “In Turkey, the regime slides from soft to hard totalitarianism”, in Open Democracy

- 3:

- T24, “Ekrem İmamoğlu'ndan Taksim açıklaması: Herkesin zevk alacağı bir alana dönüştüreceğiz” [“A declaration by Ekrem Imamoğlu on Taksim: we will turn it into a space everyone will be able to enjoy”]