Rudolph Schindler, the Austrian architect who became a Californian, in the continuous intertwining of his story with Richard Neutra’s, ended up sharing the paternity of what is usually identified as California Modern. His European education, subsequently contaminated by multiple trajectories of cultural exchange that were making Modern an International Style between the wars, soon translated into iconic works such as the Lovell Beach House in Newport Beach, or Schindler’s West Hollywood residence. In the late 1920s, a prominent family from the thriving cosmopolitan Los Angeles scene of which his architecture was an expression commissioned him to design a house on Santa Catalina Island, in the middle of the ocean, still facing L.A. Domus published the project in December 1987, on issue 689, to celebrate the architect’s centenary.

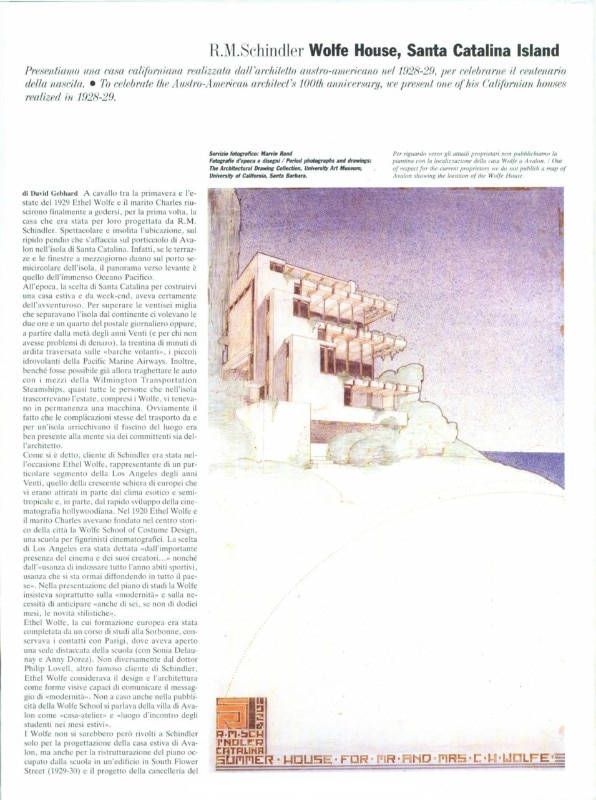

R.M.Schindler. Wolfe House, Santa Catalina Island

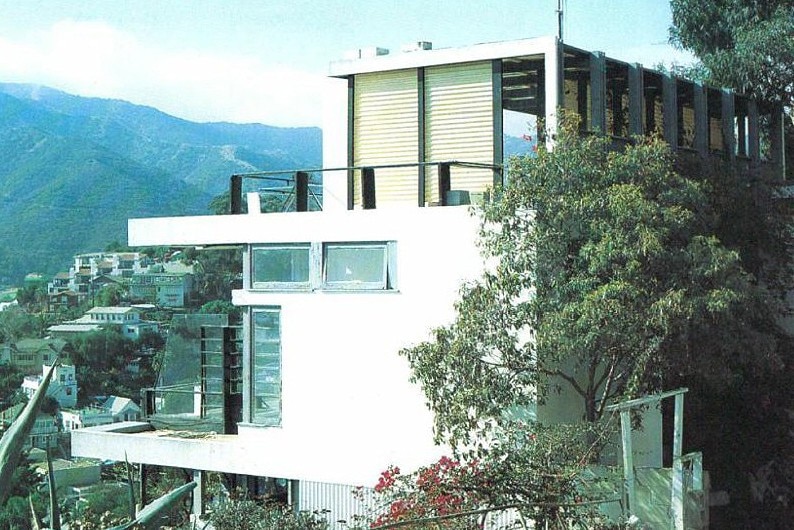

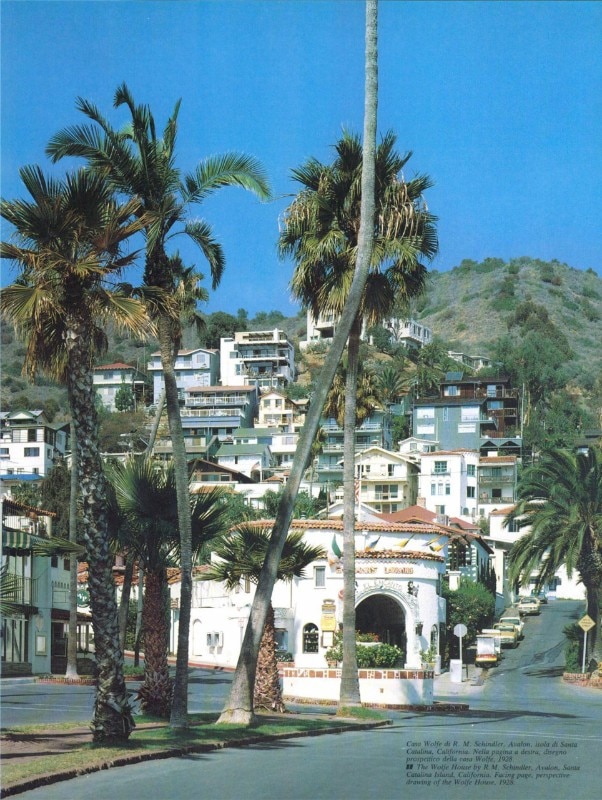

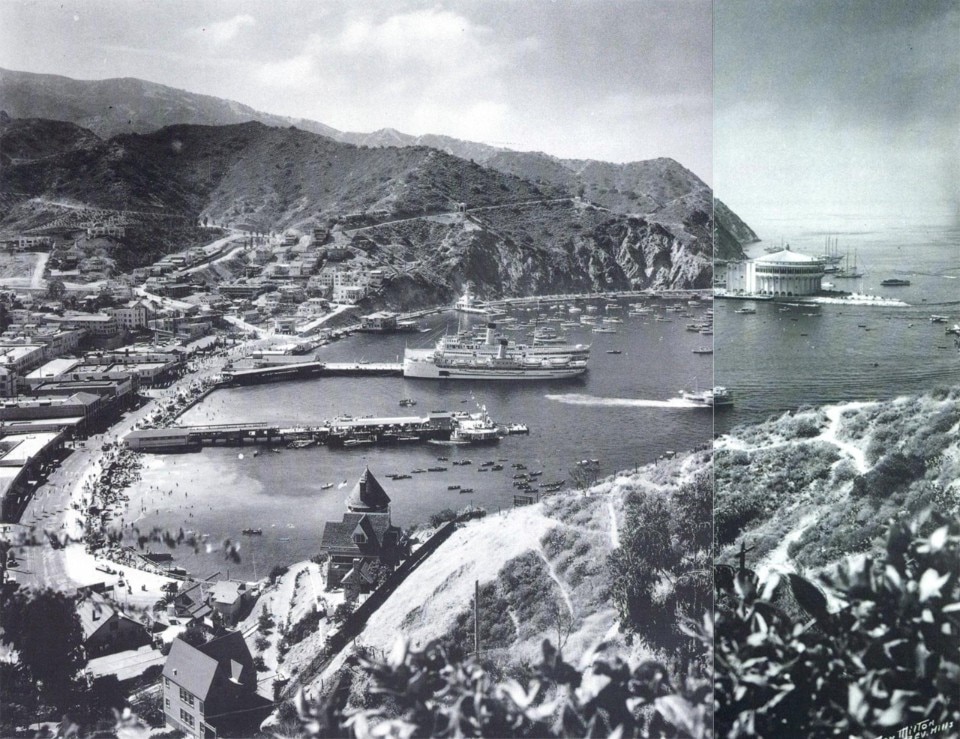

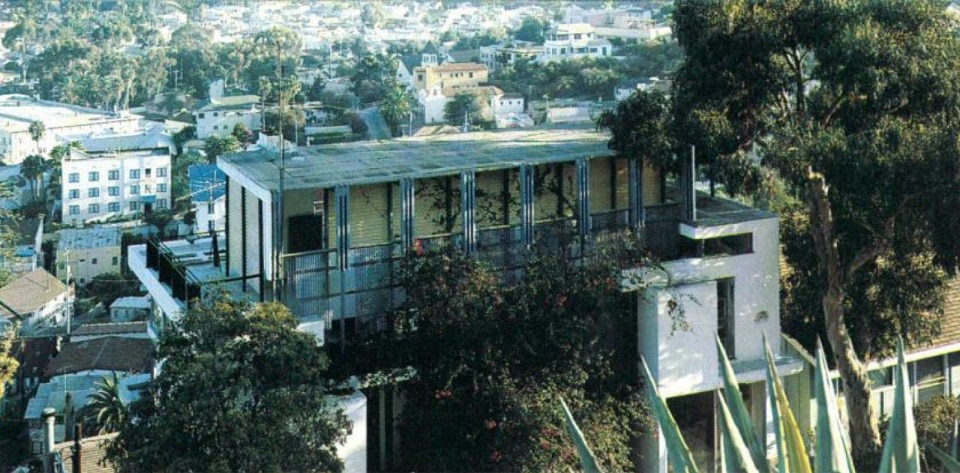

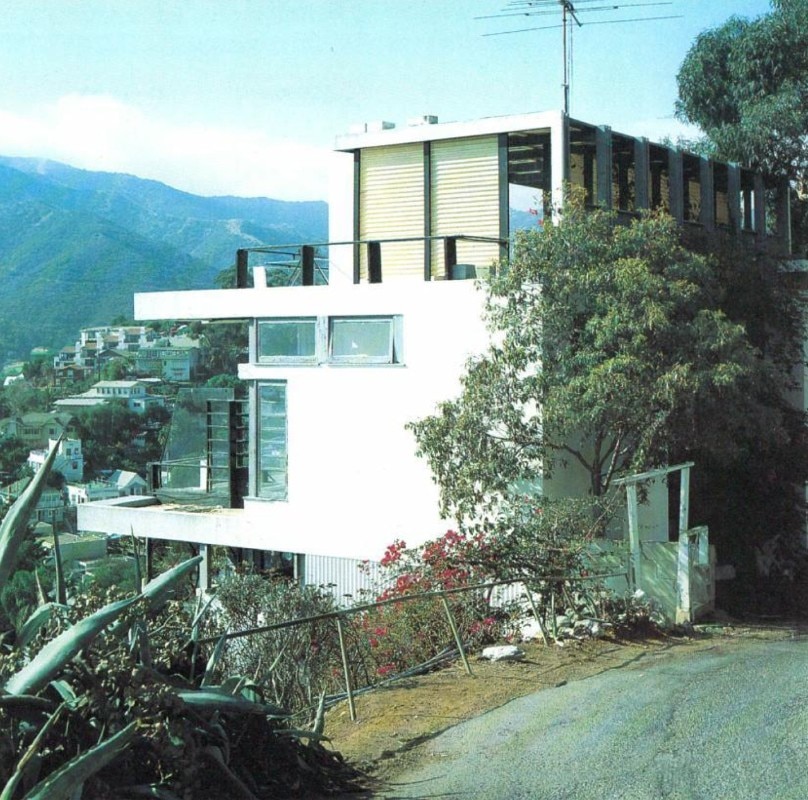

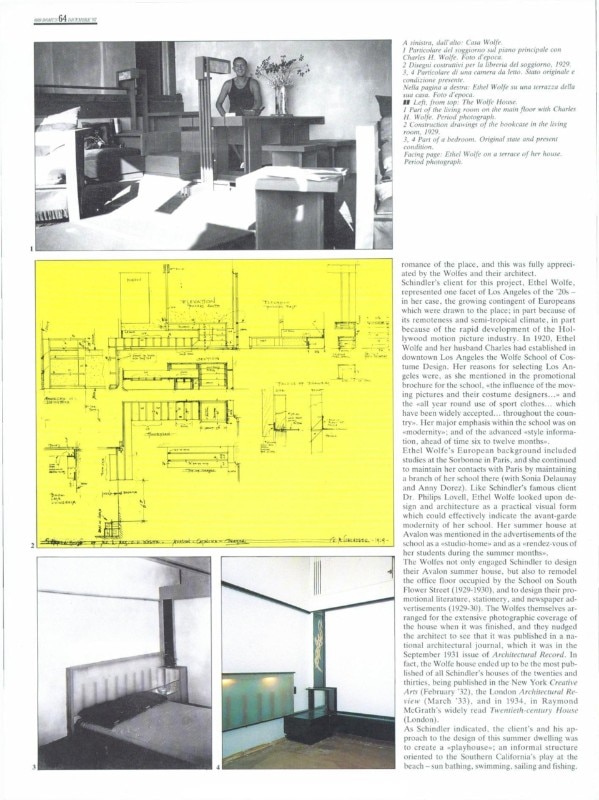

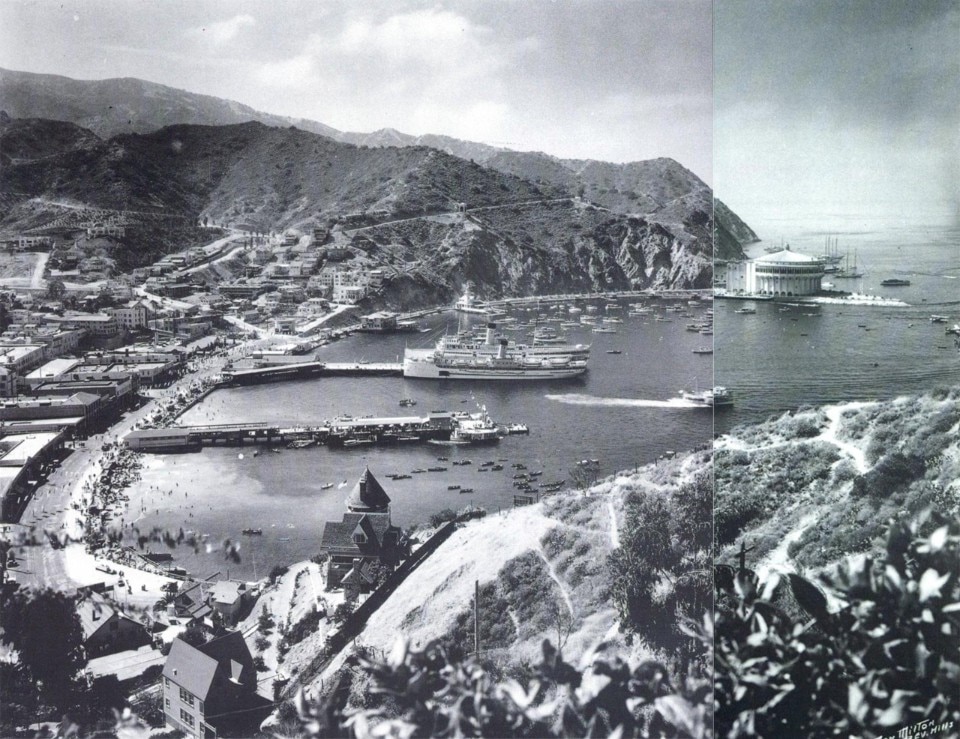

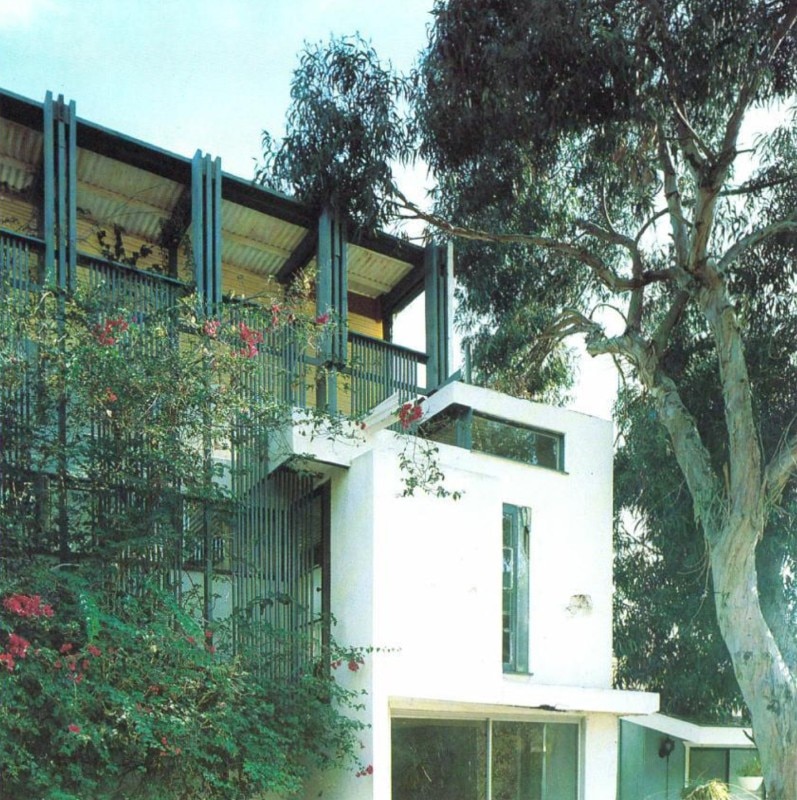

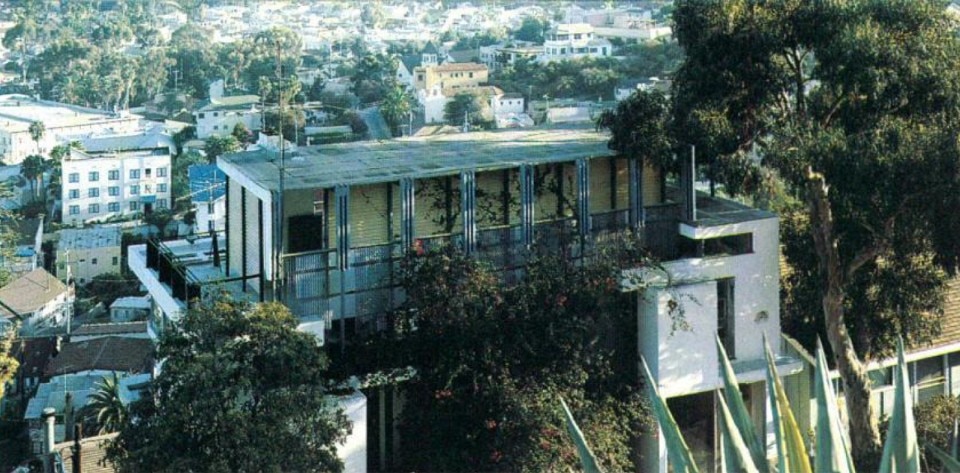

In the late spring and early summer of 1929, Ethel Wolfe and her husband Charles were able to enjoy for the first time the summer house which had been designed for them by Rudolph Michael Schindler. The location of the house, on a steep hillside overlooking the small port of Avalon on Santa Catalina Island, was both spectacular and unusual. Looking from the terrace decks and windows to the south was the entire semi-circular harbor itself; while the view to the east was that of the open Pacific Ocean.

The selection of Catalina Island as a location for a summer and weekend house was on the adventuresome side. The methods of traveling the twenty-six miles from the mainland were via a two hour and fifteen minute trip on the daily steamboat, or if money was no object from the mid 1920s on the adventure of Pacific Marine Airways’s «Flying Boats». Though automobiles could be brought over on one of the Wilmington Transportation Steamships, most individuals who summered on the island simply kept a car at their residence as the Wolfes did. Of course, all of the complication of transporting oneself to an island was part of the romance of the place, and this was fully appreciated by the Wolfes and their architect.

Schindler’s client for this project, Ethel Wolfe, represented one facet of Los Angeles of the ’20s – in her case, the growing contingent of Europeans which were drawn to the place; in part because of its remoteness and semi-tropical climate, in part because of the rapid development of the Hollywood motion picture industry. In 1920, Ethel Wolfe and her husband Charles had established in downtown Los Angeles the Wolfe School of Costume Design. Her reasons for selecting Los Angeles were, as she mentioned in the promotional brochure for the school, “the influence of the moving pictures and their costume designers...” and the “all year round use of sport clothes... which have been widely accepted... throughout the country”. Her major emphasis within the school was on “modernity”; and of the advanced “style information, ahead of time six to twelve months”.

Ethel Wolfe’s European background included studies at the Sorbonne in Paris, and she continued to maintain her contacts with Pans by maintaining a branch of her school there (with Sonia Delaunay and Anny Dorez). Like Schindler’s famous client Dr. Philips Lovell, Ethel Wolfe looked upon design and architecture as a practical visual form which could effectively indicate the avant-garde modernity of her school. Her summer house at Avalon was mentioned in the advertisements of the school as a “studio-home” and as a “rendez-vous of her students during the summer months”.

The Wolfes not only engaged Schindler to design their Avalon summer house, but also to remodel the office floor occupied by the School on South Flower Street (1929-1930), and to design their promotional literature, stationery, and newspaper advertisements (1929-30). The Wolfes themselves arranged for the extensive photographic coverage of the house when it was finished, and they nudged the architect to see that it was published in a national architectural journal, which it was in the September 1931 issue of Architectural Record. In fact, the Wolfe house ended up to be the most published of all Schindler’s houses of the twenties and thirties, being published in the New York Creative Arts (February ’32), the London Architectural Review (March ’33), and in 1934, in Raymond McGrath’s widely read Twentieth-century House (London).

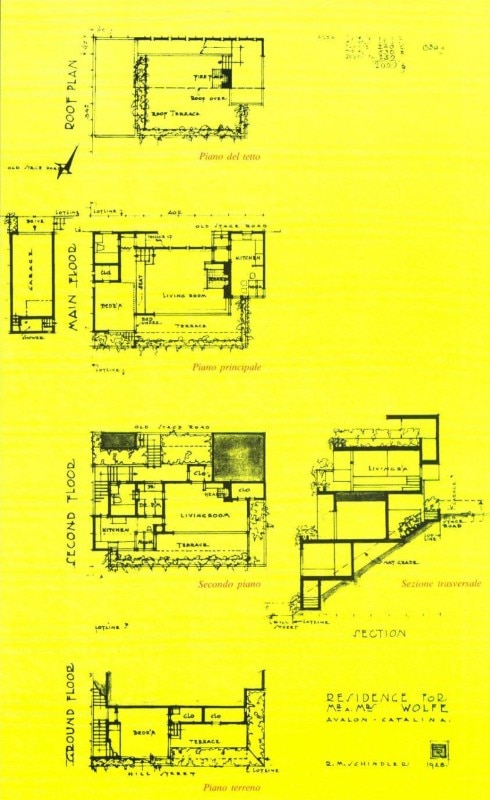

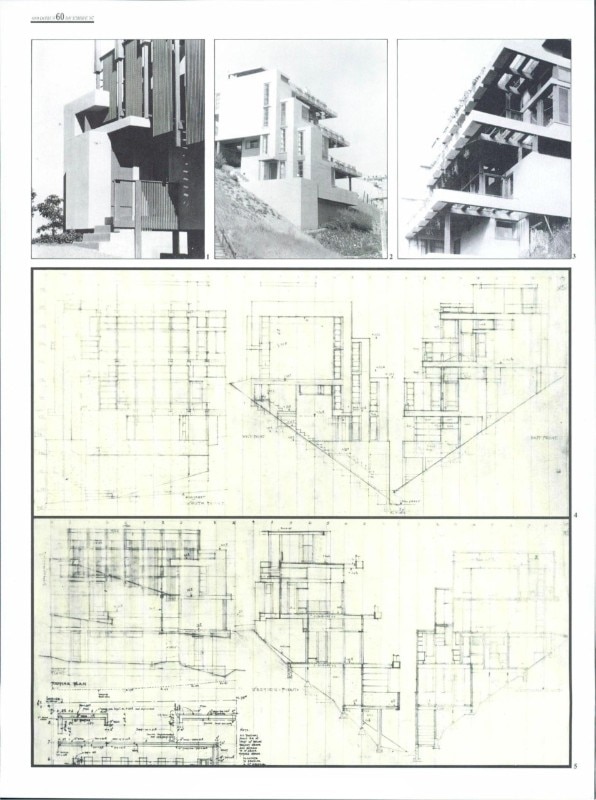

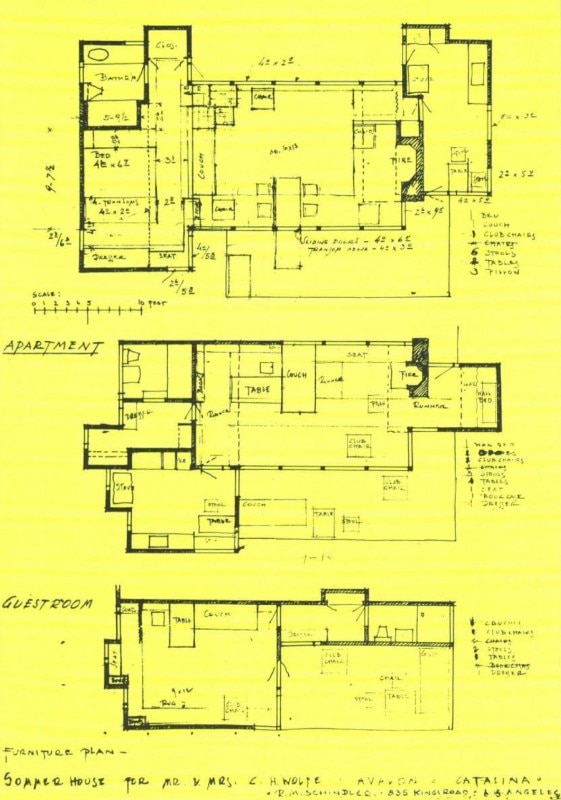

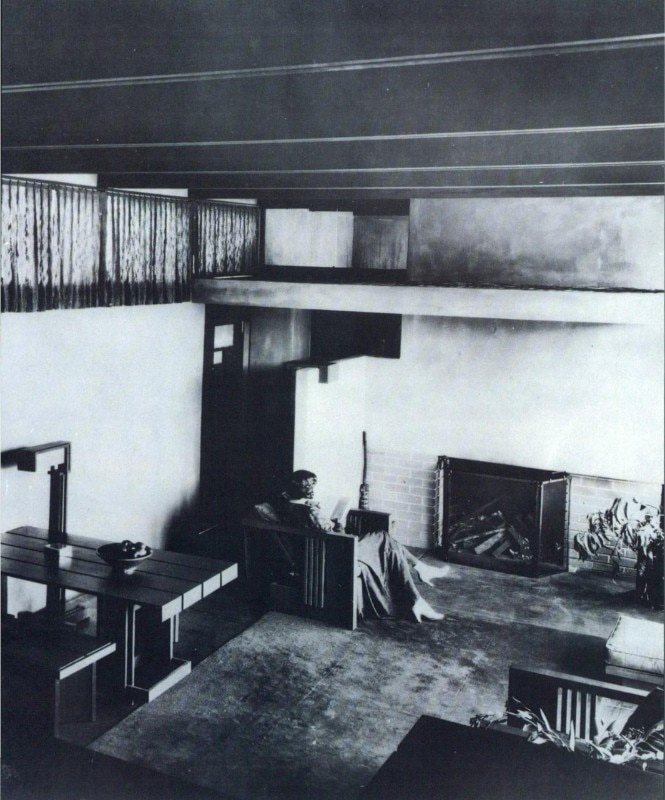

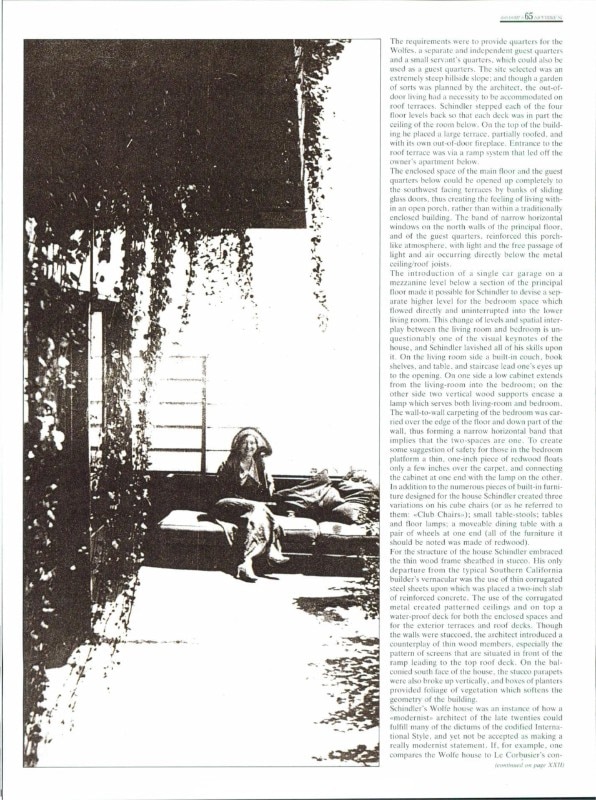

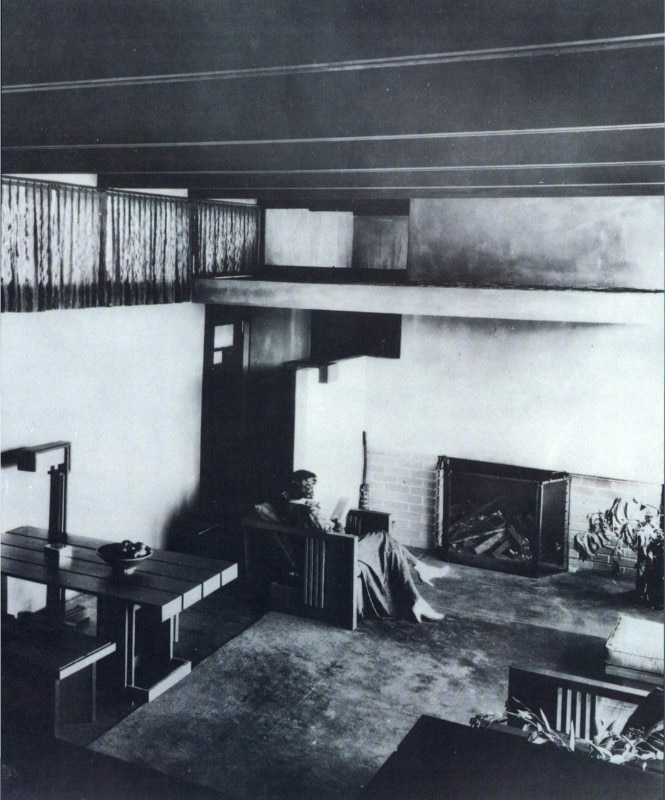

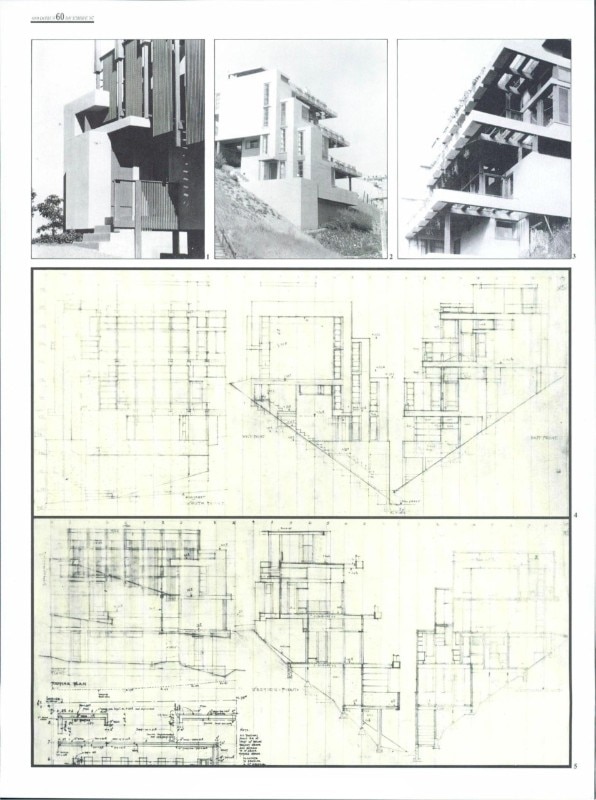

As Schindler indicated, the client’s and his approach to the design of this summer dwelling was to create a “playhouse”; an informal structure oriented to the Southern California’s play at the beach - sun bathing, swimming, sailing and fishing. The requirements were to provide quarters for the Wolfes, a separate and independent guest quarters and a small servant’s quarters, which could also be used as a guest quarters. The site selected was an extremely steep hillside slope: and though a garden of sorts was planned by the architect, the out-of-door living had a necessity to be accommodated on roof terraces. Schindler stepped each of the four floor levels back so that each deck was in part the ceiling of the room below. On the top of the building he placed a large terrace, partially roofed, and with its own out-of-door fireplace. Entrance to the roof terrace was via a ramp system that led off the owner’s apartment below. The enclosed space of the main floor and the guest quarters below could be opened up completely to the southwest facing terraces by banks of sliding glass doors, thus creating the feeling of living within an open porch, rather than within a traditionally enclosed building. The band of narrow horizontal windows on the north walls of the principal floor, and of the guest quarters, reinforced this porch-like atmosphere, with light and the free passage of light and air occurring directly below the metal ceiling/roof joists.

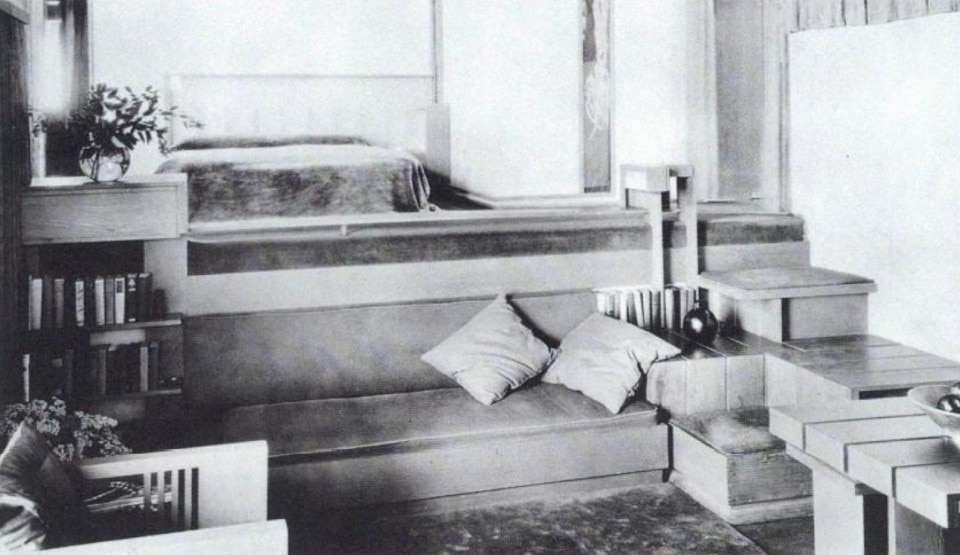

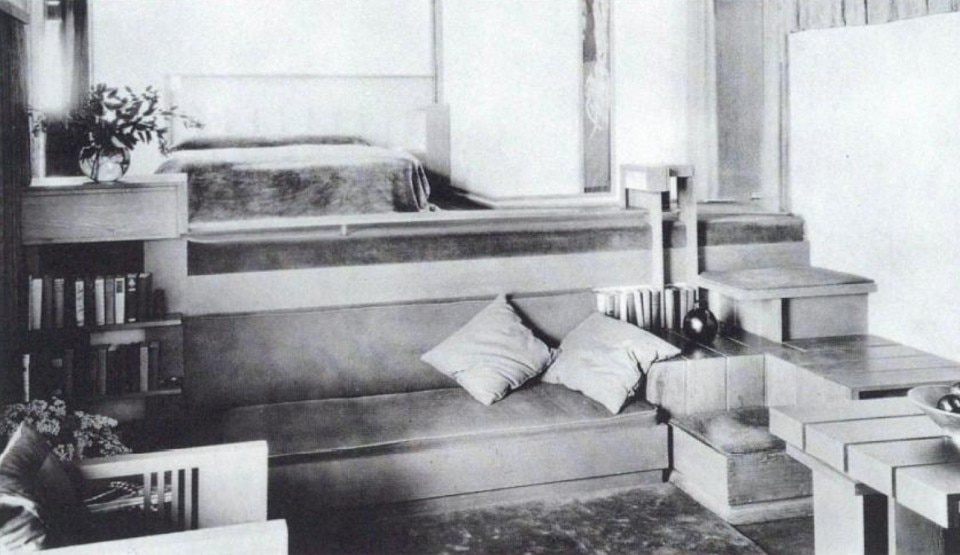

The introduction of a single car garage on a mezzanine level below a section of the principal floor made it possible for Schindler to devise a separate higher level for the bedroom space which flowed directly and uninterrupted into the lower living room. This change of levels and spatial interplay between the living room and bedroom is unquestionably one of the visual keynotes of the house, and Schindler lavished all of his skills upon it. On the living room side a built-in couch, book shelves, and table, and staircase lead one's eyes up to the opening. On one side a low cabinet extends from the living-room into the bedroom; on the other side two vertical wood supports encase a lamp which serves both living-room and bedroom. The wall-to-wall carpeting of the bedroom was carried over the edge of the floor and down part of the wall, thus forming a narrow horizontal band that implies that the two-spaces are one. To create some suggestion of safety for those in the bedroom platform a thin, one-inch piece of redwood floats only a few inches over the carpet, and connecting the cabinet at one end with the lamp on the other.

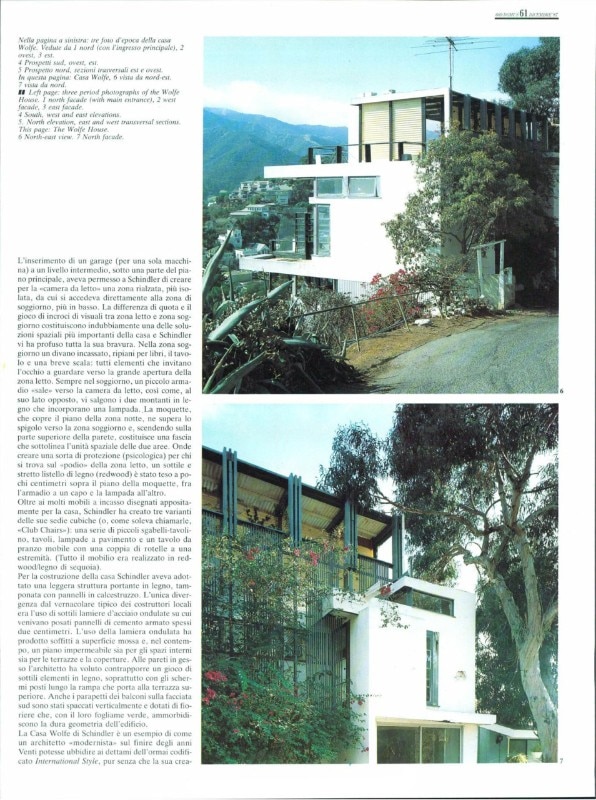

In addition to the numerous pieces of built-in furniture designed for the house Schindler created three variations on his cube chairs (or as he referred to them: “Club Chairs”); small table-stools; tables and floor lamps; a moveable dining table with a pair of wheels at one end (all of the furniture it should be noted was made of redwood). For the structure of the house Schindler embraced the thin wood frame sheathed in stucco. His only departure from the typical Southern California builder’s vernacular was the use of thin corrugated steel sheets upon which was placed a two-inch slab of reinforced concrete. The use of the corrugated metal created patterned ceilings and on top a water-proof deck for both the enclosed spaces and for the exterior terraces and roof decks. Though the walls were stuccoed, the architect introduced a counterplay of thin wood members, especially the pattern of screens that are situated in front of the ramp leading to the top roof deck. On the balconied south face of the house, the stucco parapets were also broke up vertically, and boxes of planters provided foliage of vegetation which softens the geometry of the building.

Schindler’s Wolfe house was an instance of how a “modernist” architect of the late twenties could fulfill many of the dictums of the codified International Style, and yet not be accepted as making a really modernist statement. If, for example, one compares the Wolfe house to Le Corbusier’s contemporary Villa Savoye, one will quickly discover that the two houses have much in common; they both distance themselves from their sites, floating over and above the ground. Indoor/outdoor connections, open flowing interior space, ramp systems, life out-of-doors, not on the ground, but upon terraces and roof tops, etc. Yet, the two buildings are obviously miles apart. Le Corbusier’s villa is a beautiful abstract symbol of the transportation machine, transformed into a high art object; Schindler’s starts with the premise of the common place contractor's stucco box, and makes it all read as a complex aesthetic statement. The colors of Le Corbusier’s villa are of the subtlety which one would associate with the palette of a painter; Schindler colored the stucco and wood of his building in a sand colored finish to “organically” match, as he said the surrounding sun dried hills. The underside of his corrugated metal ceiling, he painted dull gold to hint at metal which has aged over the years. Schindler characterized what he was seeking to accomplish in the Wolfe house when he wrote of it in 1930; “Design consciously abandons the conventional conception of the house as being a carved mass of honeycomb material protruding from the mountain, for the sake of creating a composition of space units in and of the atmosphere above the hill”.

David Gebhard

Collection, University Art Museum, University of Califomia, Santa Barbara. Marvin Rand Period photographs and drawings: The Architectural Drawing Collection, University Art Museum, University of Califomia, Santa Barbara.