You live in the vicinity of Turin, a region that has perhaps in influenced the history of car styling more than any other in the world. What aspects do you think characterised the postwar period in which visionary individuals, from Giovanni Bertone to Camillo Olivetti, and from Carlo Mollino to yourself, made Turin an epicentre of industrial and design innovation not only in Italy but also worldwide?

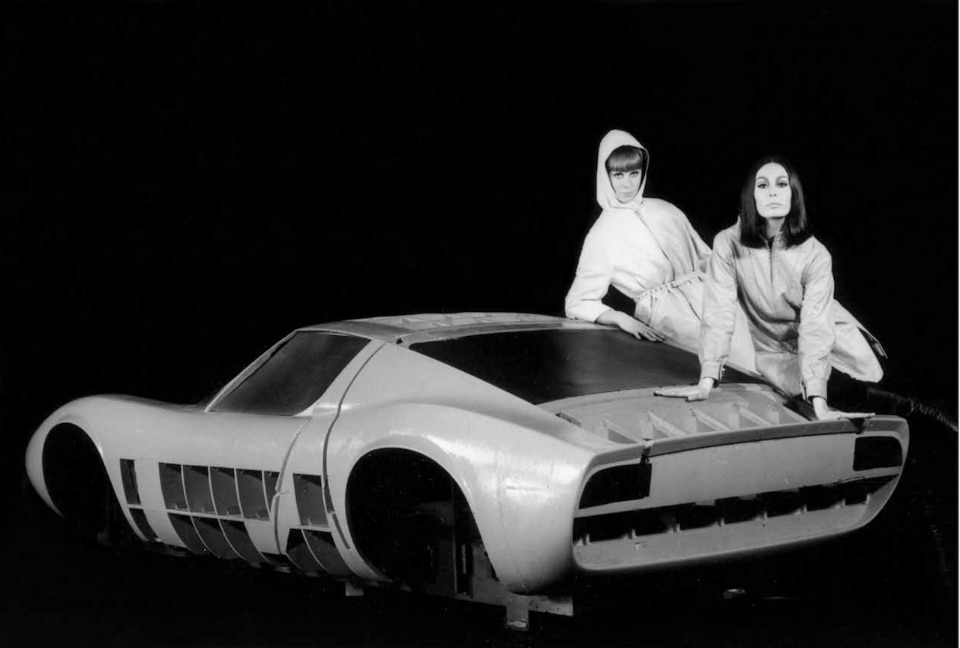

Marcello Gandini It may sound paradoxical, but this industrial innovation largely relied on the presence of highly quali ed traditional craftsmen. The car sector in particular benefited from the great number of extremely capable frame-builders, or scoccai, and panel-beaters who fixed the sheet metal over the wood framework. Traditionally these artisans used to work on the old wooden coach boxes, and after the war they found themselves out of work. Turin had this amazing capacity to make models of prototypes. And where there’s the ability to make things, you will also find demand. As a result, many people had the opportunity to enter the sector as car designers or draughtsmen. Especially here in Turin, there weren’t any real car designers in the true sense of the term until after the war. Before that period, the real designer was actually the customer. The bloke who wanted a custom-built Ferrari, or a Lancia bodied in a particular way, would go to the frame-builders and try to explain what he wanted.

Almost a car-tailor, you might say.

They were very highly skilled craftsmen. They would take the chassis and stretch wire over it to simulate the lines of its bodywork. And then

the customer would say: “Okay, but I’d like it a bit longer.” In those days this was the body-styler. My first car was made like that, by pulling up these wires at an obscure car body-maker’s, with a man who mostly did repair work. The aluminium would be hammered and the metal plates were formed, just by using these lengths of wire. After this the wires were removed and the frames were made to support the body-shell panels. I started with racing cars, working with people who competed in uphill races with a souped-up Fiat 600, and had a few liras to spend on modifying the bodywork.

So it was actually more like making the car than designing it.

In those days there was no proper drawing, at the most a rough sketch. At the beginning of my career, when I used to work for Bertone, an old boy came in one day who had a hotel chain in Hawaii. This chap wanted a Rolls Royce custom-built for him. By then things like that were seldom done any more, but he had a very pretty young wife who did the drawings. So this guy arrived with little sketches of how he wanted this Rolls Royce to look. He was the typical client from the pre-industrial era of motoring.

Today would that be called customisation?

You could say that, but there were practical purposes too. I remember a fellow who had bought one of the rst Abarth Zagatos, the one with the hunched back. He wanted to make it lighter, and as it was derived from the Fiat 600 and had a rear engine fixed to a crossbar at the bottom, we sawed off the tail end. So as not to leave moving pulleys and sheaves uncovered, we tted a wire net that looked like a henhouse.

This way of working you describe is very different from today’s situation in the car industry.

That’s right. A style centre today is made up of hundreds of people.

Is real innovation still possible in this kind of context?

There’s a problem that’s always existed, but it’s perhaps the central issue today: everybody would like innovation but nobody is prepared to start from scratch. Real innovation nearly always stems from the presence of some highly charismatic gure in the company, coupled with the company’s willingness to realise this individual’s vision, or even his fantasies. The most glaring example is Flaminio Bertoni’s Citroën DS19. Bertoni was a genius but also an absolute autocrat who managed to condition company choices to the point of carrying through projects that made no sense according to industrial logic, even though almost without exception they turned out to be brilliant.

The DS19 was a car of great inspiration to the world of architecture. Alison Smithson even wrote a short book on it.

It influenced many sectors in the field of design. The story of the DS19 clearly shows that innovation requires one mind; you can’t have a collaboration among 100 or 200 people. They can move in afterwards, when there are snags to be solved, but the initial concept has to be the fruit of a strong personal vision.

Your cars are all very different. One could say that there is no unifying style.

Let’s say that the best-known ones are not so much innovations of form but rather innovations in the kind of approach.

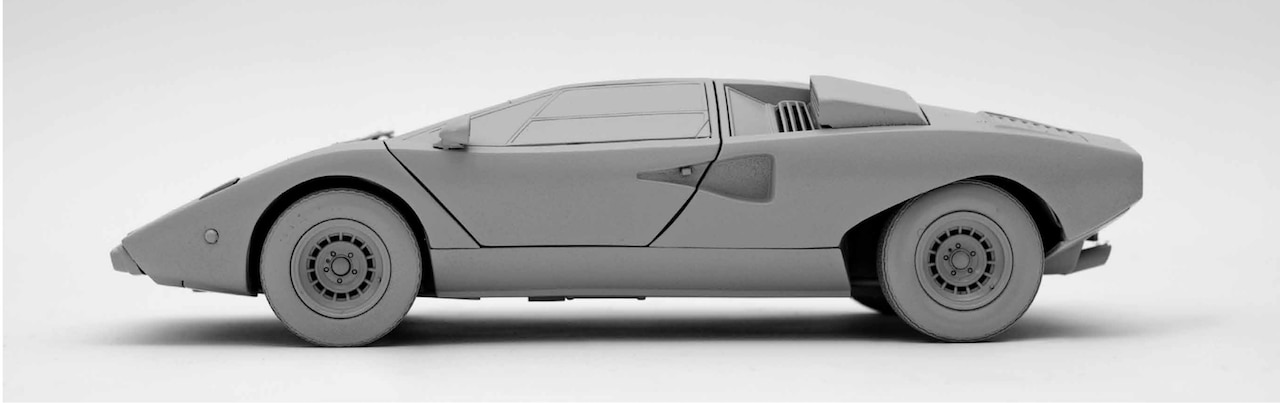

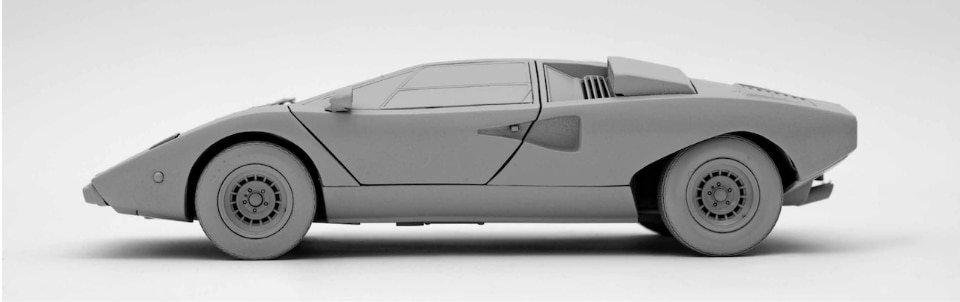

That’s true, but if we think about the Lamborghini Countach, it was one of the very few examples in car history where a genuinely new and original form was developed.

The fact is that the Countach represented a clean break from some of the car industry’s consolidated practices. It didn’t refer to any other previous cars. It was not in people’s eyes; tastes had not been educated to appreciate it. Initially it was a culturally alien form, but within a few years it became an object-symbol. It stayed in production for 17 years. Even now the designers at Audi tell me it’s a source of inspiration for the cars they make. Lamborghini’s Miura, on the other hand, is a different story. It had innovative details, but as a whole it was already accepted in everybody’s eyes at the moment of its launch.

How long did it take to research the Miura?

A month or two. In the autumn of 1965, Ferruccio Lamborghini, Paolo Stanzani and Gianpaolo Dallara came to me and proposed that I work with them on a project. I didn’t start straight away because I still had a few projects to nish, so in the end I produced the first sketches in late November. I remember that by 10pm on Christmas Eve, 24 December 1965, we had practically finished the model in wood and ecowood. We managed to beat Father Christmas to it by a couple of hours. Then the car was made in January and February and presented in March.

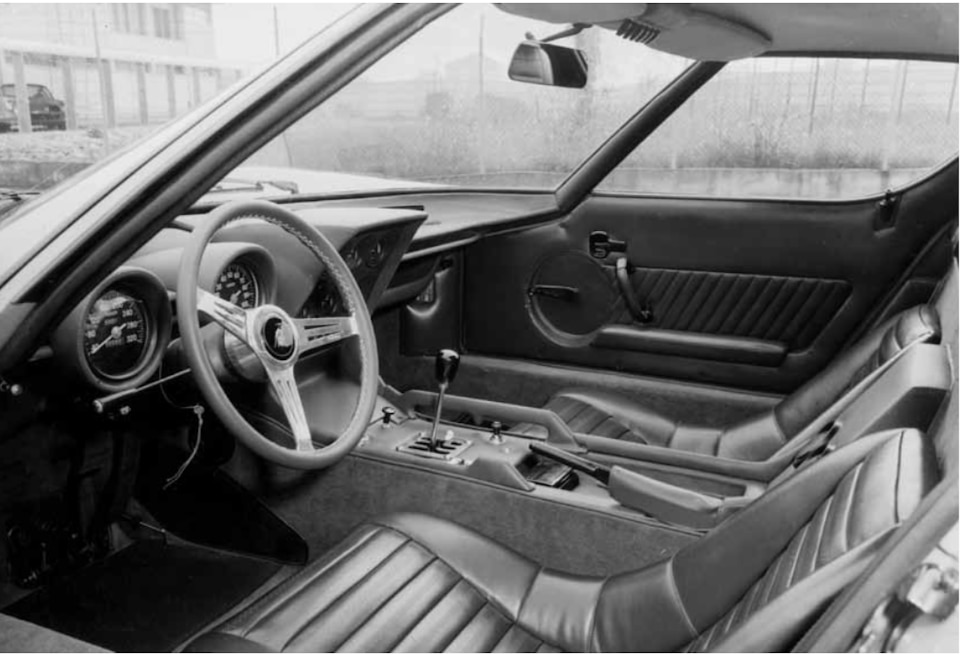

That’s astoundingly quick if one thinks of the virtually geological time scales needed for the conception of a car nowadays. Did you also work on the interiors?

Yes, I did the lot. At that time interiors weren’t as sophisticated as they are now. It so happened that I did them in one night: drawing and construction.

A colleague of yours, Chris Bangle, who until recently was head of BMW’s style office, used to say that in his designs one of the key aims was to give the car an innate dynamism, even when it’s not moving.

Movement is part of this type of aesthetic. I must say I don’t readily deal with static objects. I’m less interested in forms that inspire the sensation of movement than I am in movement that in uences form. A car that suggests movement when not in motion is not necessarily more beautiful.

What is your recollection of the Countach? A photo, a drawing?

Nothing, really. Perhaps if I look hard, I might nd the odd photo of the prototype. My archive is generally the waste paper basket, which I keep under here. I prefer the archive of memory: it easily erases the disagreeable items.