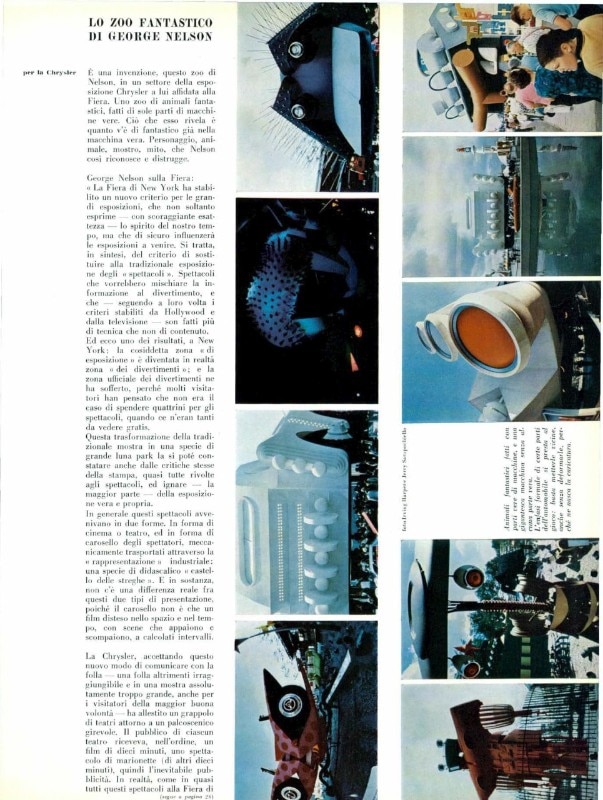

In addition to being a milestone name in design, George Nelson was a great shaper of imaginaires, meanings and identities: just think of the Herman Miller brand he directed for a long time, which became synonymous with American modernism. At the 1964 New York World Fair, where also Eames realised his theatre of information, Nelson would in fact reflect meaning before construction: instead of proceeding in conventionally developing the order, a pavilion for Chrysler, he chose with his firm to look at the fair as a spectacle. In addition to positioning on the cutting edge of his era, by referencing the society of the spectacle, echoing situationism and embracing the language of pop, the idea of translating the Chrysler space into a zoo populated by abnormal artificial creatures born from car parts – a zoo that contained events before merchandise – anticipated many others, which came even decades later: the reflection on xeno-entities drawn from science fiction, artificial intelligence, or socio-economic phenomena such as the various art weeks, design weeks and Fuorisalone, event-based developed around trade fairs. Domus published this project in March 1965, on issue 424.

George Nelson’s fantastic zoo

One result at New York was that the so-called “exhibit” area became in effect an amusement area, and the officially designated amusement area suffered greatly, since relatively few people saw any point in spending money for shows when there were so many to be seen for nothing.

This transformation of a traditional exposition into a kind of television circus was reflected in criticism in the press, which was directed almost entirely to the shows and largely ignored the exhibits—up to this time the backbone of the traditional exposition.

The shows took two forms, generally speaking. One was the stage or film performance; the other was the mechanized ride through what has best been described as a kind of industrial tunnel of love. Basically there was no real difference between the two types of presentations, since a ride is simply a film spread out in space as well as time, with scenes appearing and disappearing at precisely timed intervals.

The Chrysler acknowledgment of this new way of dealing with mobs on an unmanagable scale in an exhibition too large to be embraced by even the most determined visitator was a cluster of theaters set about a revolving stage. An audience in any given theater was exposed in succession to a ten-minute film, then to a ten-minute puppet show, then to the inevitable “commercial”. Actually, like most of the other shows at the New York Fair, the whole thing was a thinly sugar-coated commercial.

The project entrusted to our office did not include the show but did include everything else—planning of an oval site 300 meters long with an area of about 25,000 square meters, design of all the buildings and exhibit structures, which did not contain, incidentally, the usual exhibit pavilion. It was our feeling the American public already knows quite enough about automobiles.

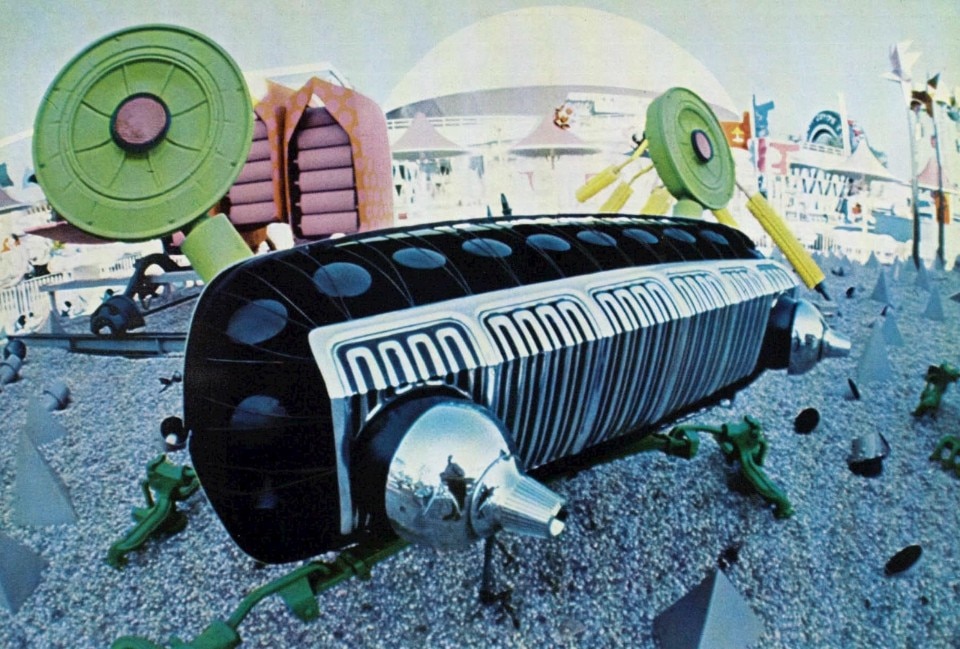

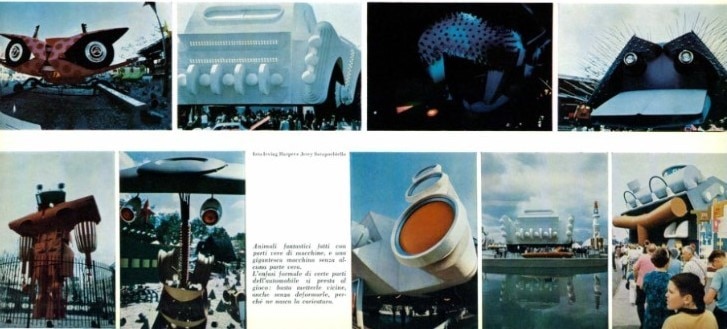

The Zoo is inhabited by improbable animals constructed of automobile parts, and the traditional fence which surrounds it is designed more to protect the animals than the people.

George Nelson

Our approach was that the theme “automobile” was extremely rich in all kinds of entertaining possibilities if these were dealt with in a lighthearted manner; and the result was a series of structures placed on islands within an artificial lake, which might be described as having some of the qualities of both fantasy and pop art. The Giant Car, for istance, was conceived as a kind of amiable monstrosity—a three-dimensional comment on the nonsense implicit in Detroit's reverentely presented “dream cars”.

The Giant Engine, so big that one can walk through it, conveys the sense of power and complexity in a motor but makes very little effort to explain it. The Assembly Line Ride is pure nonsense, since nothing is assembled and the line doesn’t go anywhere. The Zoo is inhabited by improbable animals constructed of automobile parts, and the traditional fence which surrounds it is — as in real zoos — designed more to protect the animals than the people.

For the comfort of feet, we provided 4,000 places to sit down. These were used on occasion but only in desperation, for the pressures created by the free shows were so great that most people dragged themselves through this immense, chaotic wasteland of commercialism-gone-mad with the same desperate determination as the crowds fighting to get on the subway at rush hours.

New York, one suspects, killed the traditional exposition. Unfortunately, it put nothing in its place excepting an over-size image of 1984. The Chrysler Exhibition enjoyed the happy fate of becoming a kind of oasis for people who enjoyed its relaxed pace and its quiet entertainments. For the great masses, however, the demonstrations of the victory of technique over content — already nearly complete in television — held the real fascination.