“We are heirs not only to what our fathers chose in their testamentary lists, but to everything which mankind has built up over the centuries, even beyond the barriers of western civilization”. In a long and uninterrupted exchange, which has lasted to the present day, with Domus – which he had called “an oasis in the northern Italian desert” – Paolo Portoghesi has explored the most diverse disciplinary ways and references to affirm the point that has made him one of the most important exponents of postmodernism: the point that architecture is something rooted in the depths of human history, languages, symbols, ways of seeing, and building, in the depths of their origins.

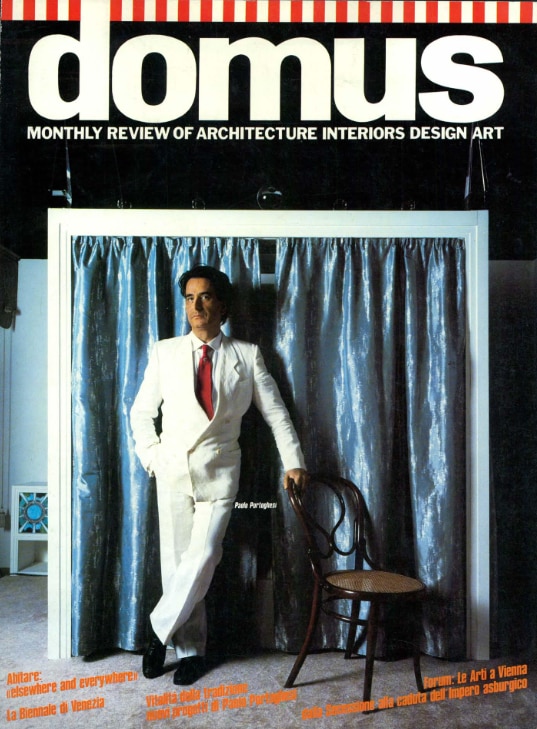

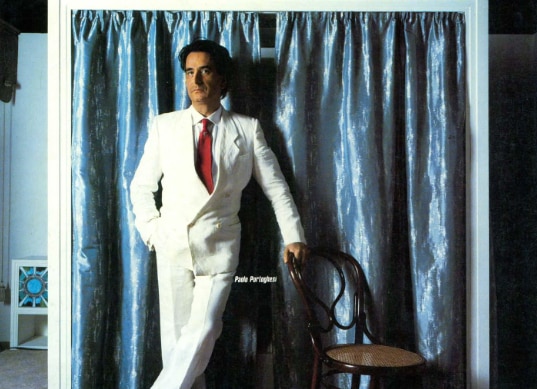

Born in Rome in 1931, died in 2023, he had been working from a very early age on his own cultural, academic, and political positioning through works – such as the ruin-inspired Baldi house and, later, the Rome Mosque – writings, books, and journals. By July 1984, when he starred on the cover of Alessandro Mendini's Domus, Portoghesi had become a reference for all Italian architectural culture, the author four years before of the operation destined to write the history of global postmodernism: the first Venice Architecture Biennale, with its Strada Novissima at the Arsenale. On issue 652, the exchange between the director and the “preacher” (as Portoghesi said to be called by Mario Ridolfi) would take on the dimensions of a manifesto, even in its conciseness.

Conversation with Paolo Portoghesi

With your “Via Novissima” for the 1980 Venice Biennale, you became the official director of post-modernism in architecture. What is left of that experience today?

The word post-modern has not yet exhausted its historical mission, which is to make people reflect upon how much what we continue to call “modern” has aged and dried up and no longer fulfils the demands of a radically changed society. It goes without saying that by the time everyone has realized this, it will also be understood that we are the true “moderns”; we’re the ones who had the courage to break with a modern which had become “immobile”, dogmatic and had lost the sense of humour that marked its distant youth. What is still very much alive in the post-modern adventure is the need to destroy the dyke which artificially separated the present perfect from the past remote. We are heirs not only to what our fathers chose in their testamentary lists, but to everything which mankind has built up over the centuries, even beyond the barriers of western civilization. Besides that, we have understood that architecture also serves to transmit and to receive information; and to communicate requires, conventions, institutions and the duration of such conventions for a long time. To this part of architecture, which does not belong to books but to what is impressed upon our memories, modern added only a very unstable and flimsy layer: the rest are still the great archetypes which classical myth had expressed with supreme clarity. Even Freud, to describe modern man and his neuroses, had recourse to the eternity of myth. So you see, those who hoped that the new wave of post-modern was just a passing ripple will have to think again. And those who thought post-modern was a New York cocktail made with one part Eisenman, one part Johnson, a dash of Graves and a drop or two of Louis Kahn, will also be surprised.

Besides my architecture, I very much like the architecture of others. I wish there could be more and more space for the beauty of architecture and that the young, who have drawen so much (drawing, too, is a weapon), could begin to get their hands dirty by constructing something.

Paolo Portoghesi

.png)

In your manifold image of politician, historian, teacher, architect and coordinator of culture and magazines, don’t you sometimes feel a nostalgia for one main vocation?

My only deep vocation is to design and build. But faced with the crisis of the architect as a professional figure I chose to fight the battle to change architecture with every possible weapon. Moreover, besides my architecture, I very much like the architecture of others. I wish there could be more and more space for the beauty of architecture and that the young, who have drawen so much (drawing, too, is a weapon), could begin to get their hands dirty by constructing something. Ridolfi says I am a “preacher”. He may be right, but together with one or two certainties I preach the praise of doubt. So I am an anomalous preacher. With Zevi I was closely associated for three years, working together on the inheritance of Michelangelo. His “critical pies” were a prefiguration of certain aspects of post-modern. Then he about-turned and became the last bastion of that loutish professionalism which he had fought so hotly. However, even among adversaries points of convergence can be found, and in the necessity to give more space to architecture we may perhaps still find an agreement.

From time to time you have designed furniture and objects. What is your position towards industrial design and crafts?

I am in a waiting position. I am waiting faithfully for design to abandon its myths and to face the problem of people’s desires and needs. That’s why I much appreciate your action in this field and believe that Domus is an oasis in the northern Italian desert.

You are an enthusiast for ancient and contemporary Islamic architecture: perhaps because it is the symbol of a religious approach to life’s problems?

Yes, Islamic architecture and its geometric games are religious experience “in action”, the contemplation of fragments of truth comprehensible to all. The mosque which I am building in Rome (after ten years of unarmed battle) is not just an Islamic temple hut a temple of universal religion of places, a dialogue of stone and concrete between two civilizations that have remained apart and incapable of grasping their deep kinship. To my mind the religion of places, the capacity for all to understand the values of others, identifying themselves with their relationship with the Earth, is an important part of the culture of peace.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)