It’s the late 1990s. The automotive world is beginning to face new questions, challenging the three pillars that had dominated car design until then: the status a vehicle conferred, its transport capacity, and performance.

Emerging priorities—low environmental impact, reduced fuel consumption, construction efficiency, and high passenger-density mobility—began to reshape the conversation. In one word: sustainability.

With this in mind, Audi engineers embarked on a project that radically transformed how cars were conceived and built. An industrial reinvention equipped with advanced materials research centers, high-performance robotic production lines, and wind tunnels, all tools that, from the very first steps, became co-design instruments alongside the designers.

A vision ahead of its time

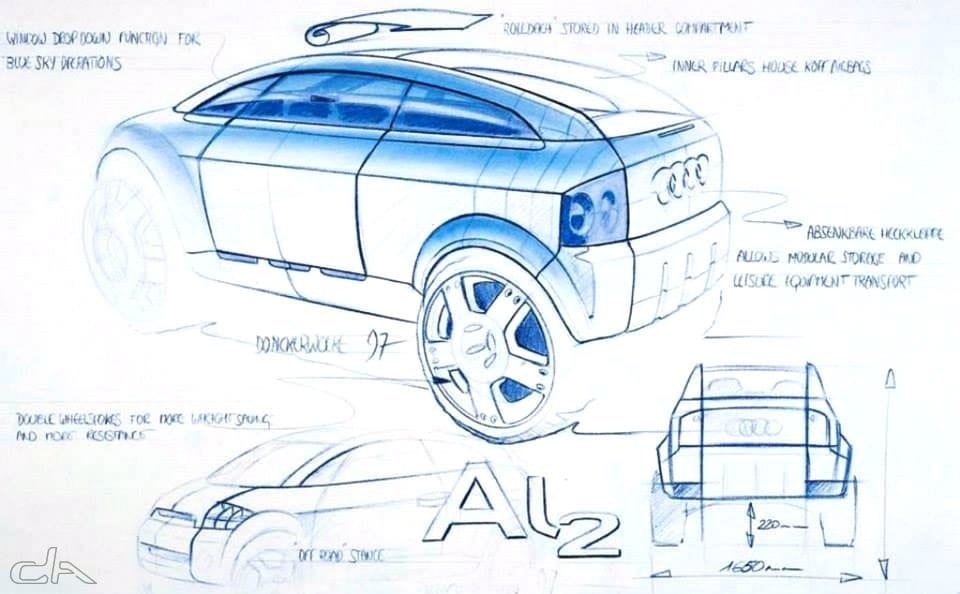

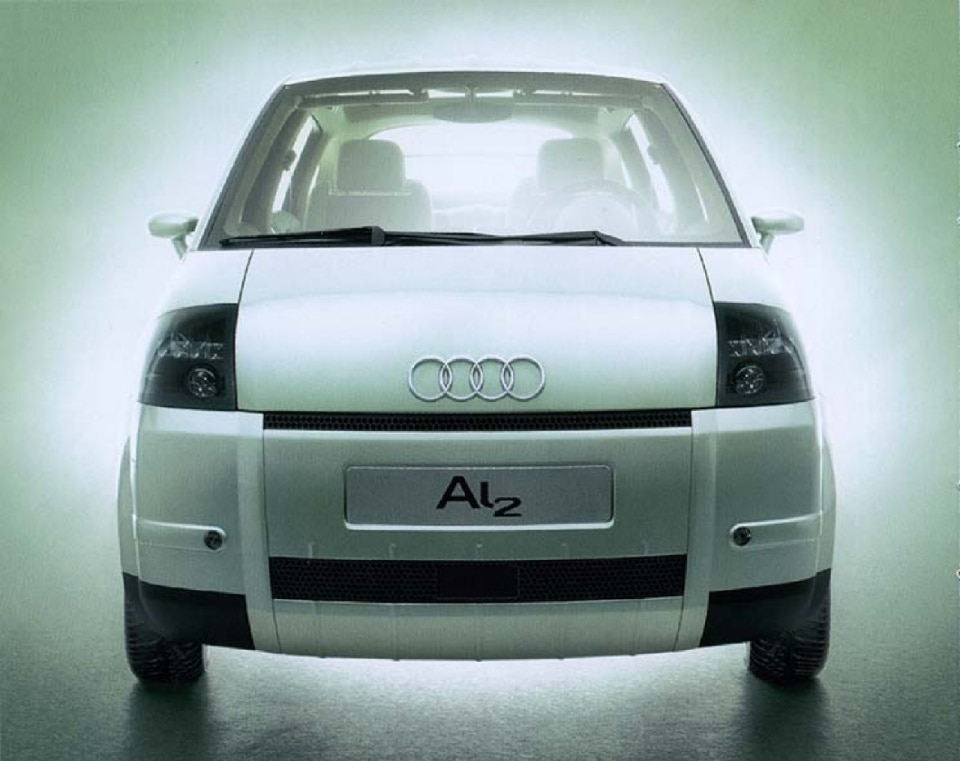

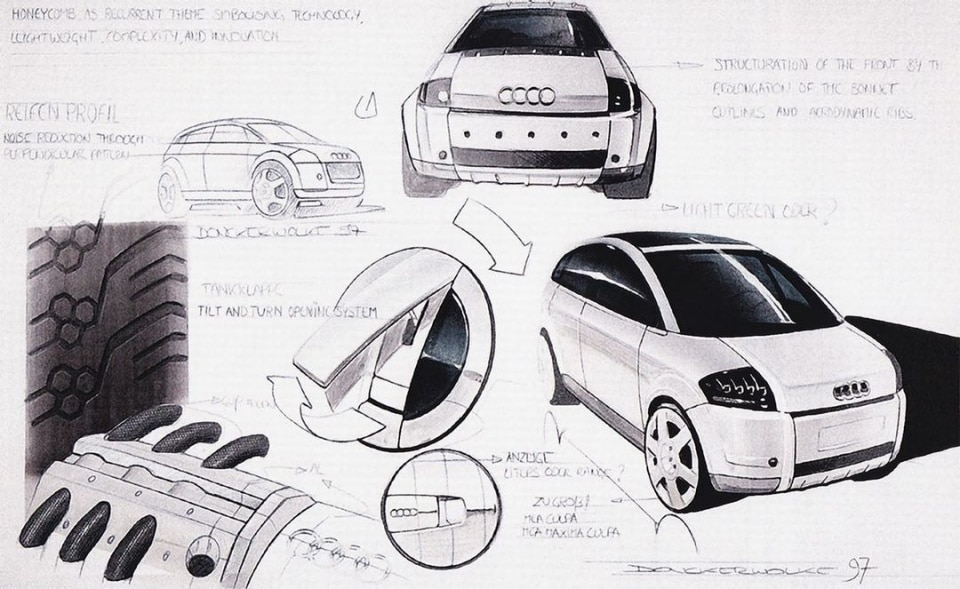

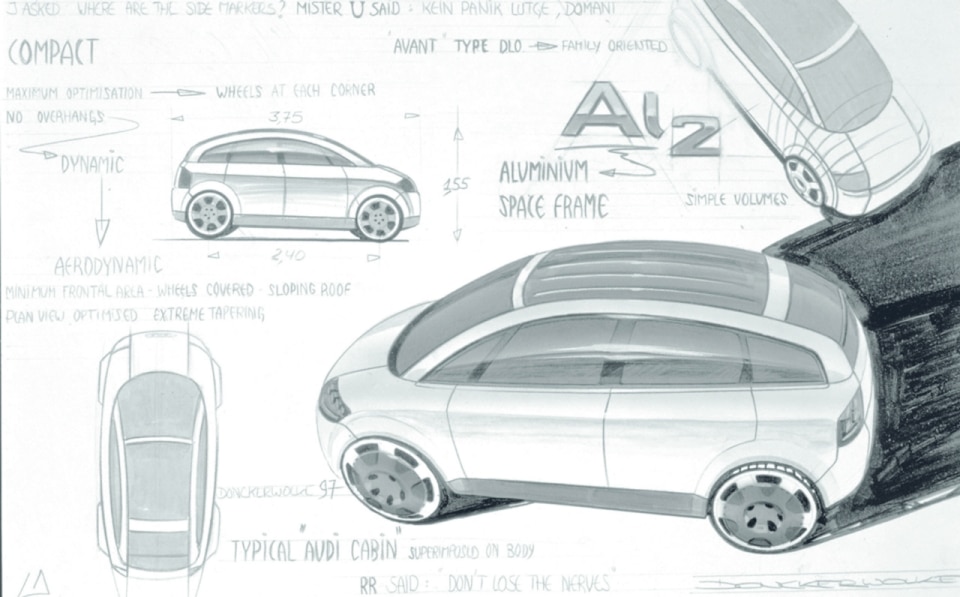

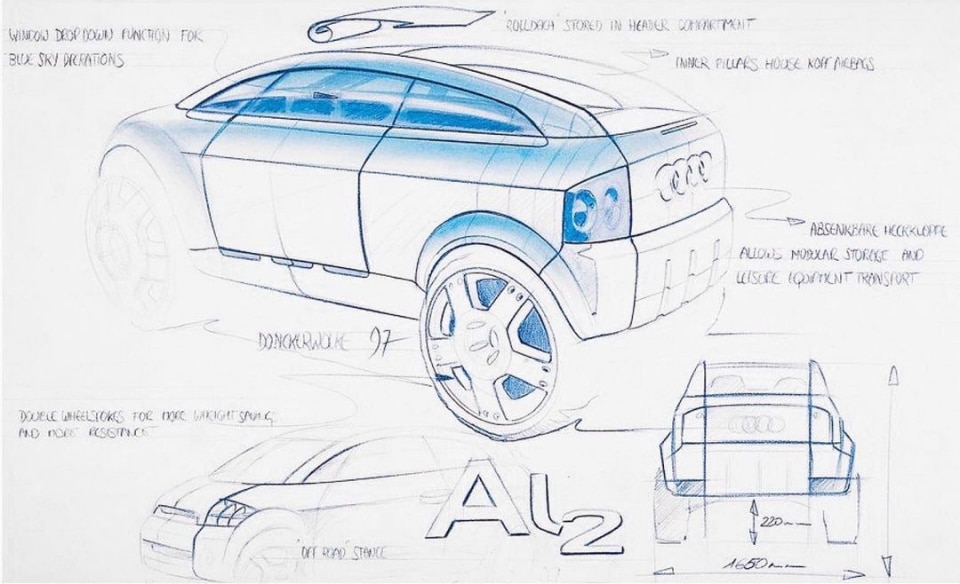

In 1997, the first concept appeared: the AL2 (and its open-end variant), presenting a new vision of mobility. Well under 4 meters (3.85 m), it was a unique family car: a mini-MPV capable of carrying 4+1 passengers in total comfort, with top-tier levels of habitability, drivability, fuel efficiency, construction efficiency, and recyclability.

The core idea was revolutionary: a self-supporting aluminum frame, something no mainstream automaker had attempted before. Hence the name, a direct nod to the periodic table.

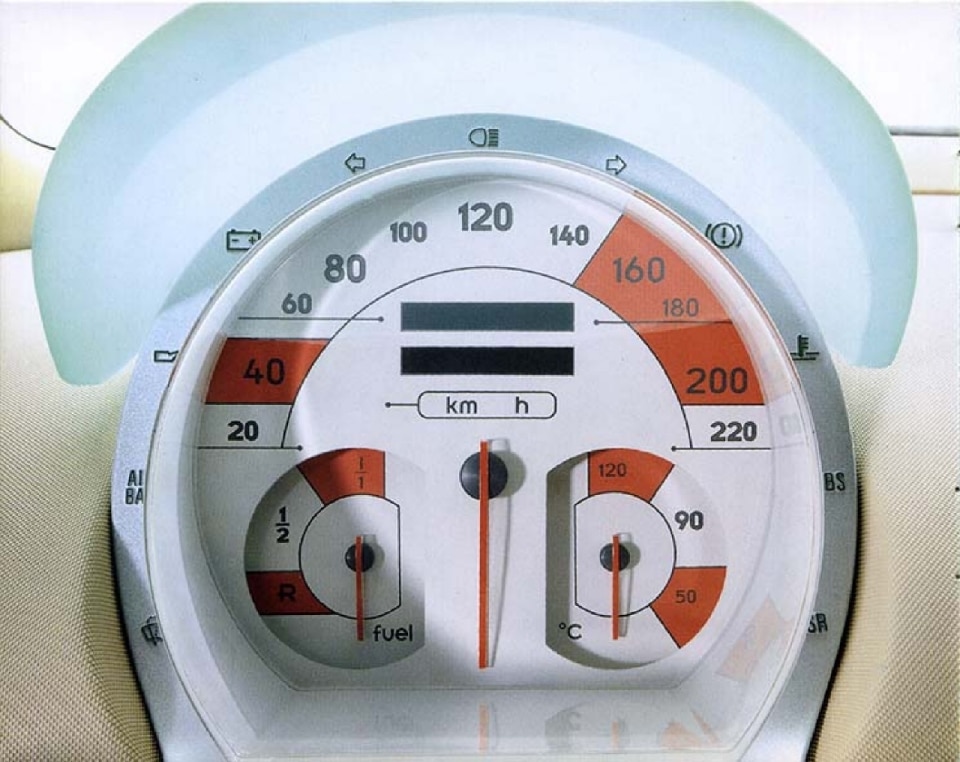

The result was an incredibly lightweight vehicle, around 800 kg, with record fuel consumption: roughly 25 km/l with the petrol engine and almost 30 km/l with the small three-cylinder automatic diesel, achievements made possible in part by Audi’s new wind tunnel, which allowed a drag coefficient of 0.24, unheard of at the time and still rare today.

July 2002: I was working at Future Systems and I remember seeing an A2 glide gracefully into our parking lot. Impossible not to notice: it looked like a tiny silver spaceship on wheels.

Andrea Morgante

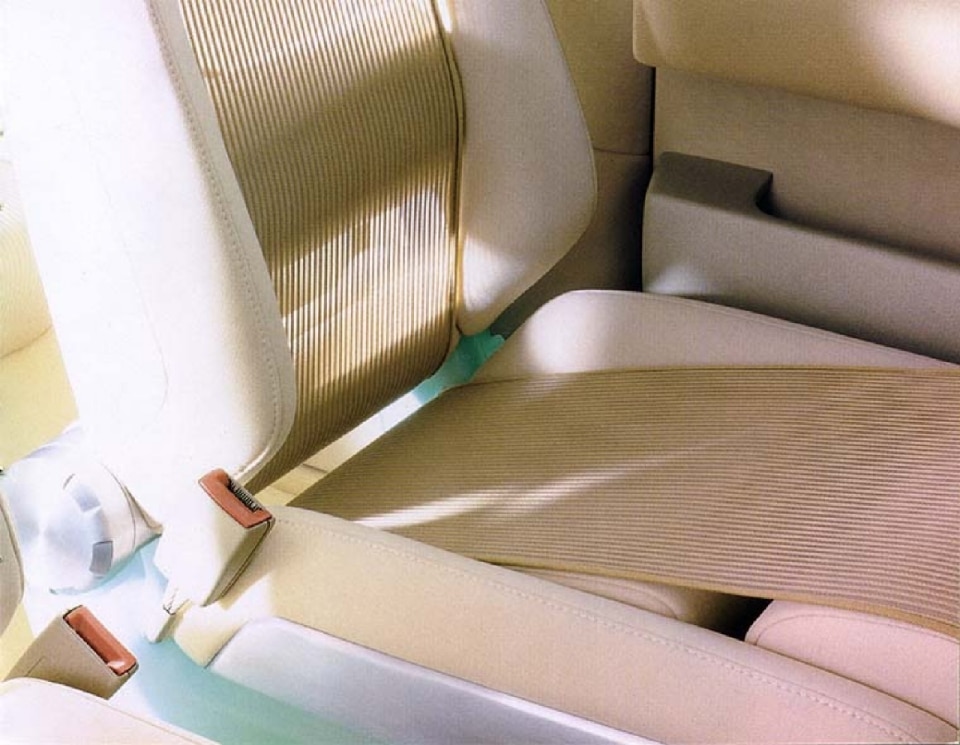

Inside, a smart layout maximized space. The hollowed floor—originally designed to house batteries for an electric version that never came—added 20 cm of legroom while lowering the seating position.

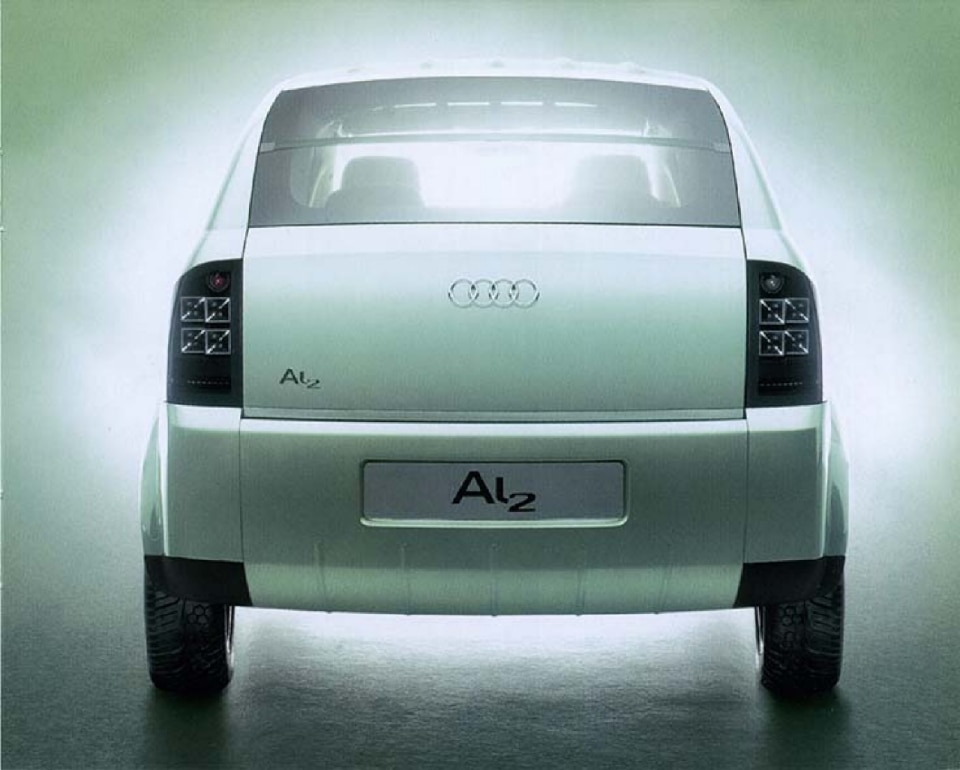

A fully glass roof, without crossbars, ran from windshield to tailgate, which could open completely, bathing the cabin in light.

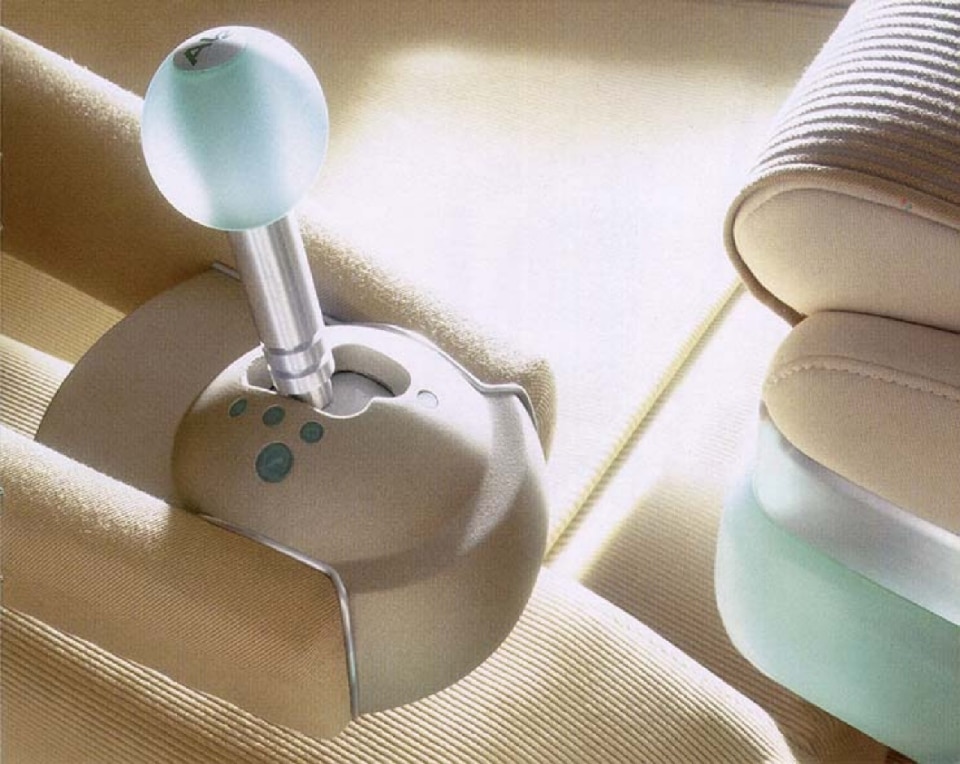

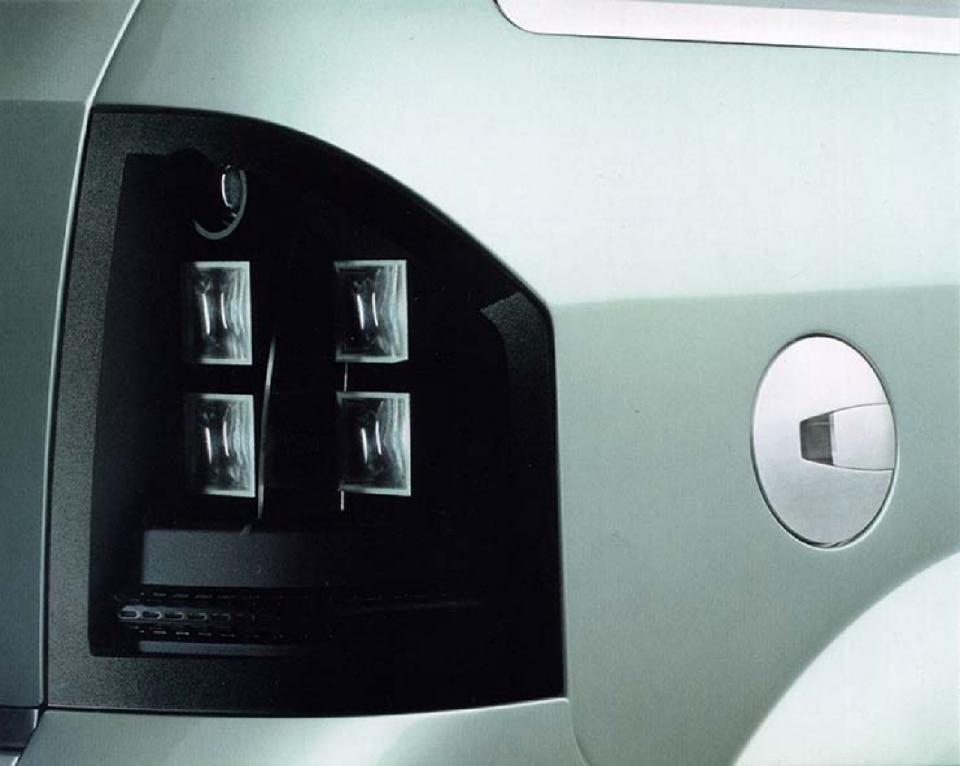

Many solutions reimagined the automotive experience: the engine hood, not meant for daily opening, could only be accessed through a small fluid refill hatch, hinting at extreme construction reliability. Rear seats, removable with a single hand and convertible into two small suitcases, increased cargo capacity. Footwells under the passengers’ feet allowed discreet storage, keeping the interior clutter-free.

When Luc Donckerwolke – also the mind behind the Lamborghini Diablo and Murciélago, the Audi TT, and other icons – arrived, the A2 reached production in 2000. His redesign was ultra-clean, landing in a car market that was, to put it mildly, shocked.

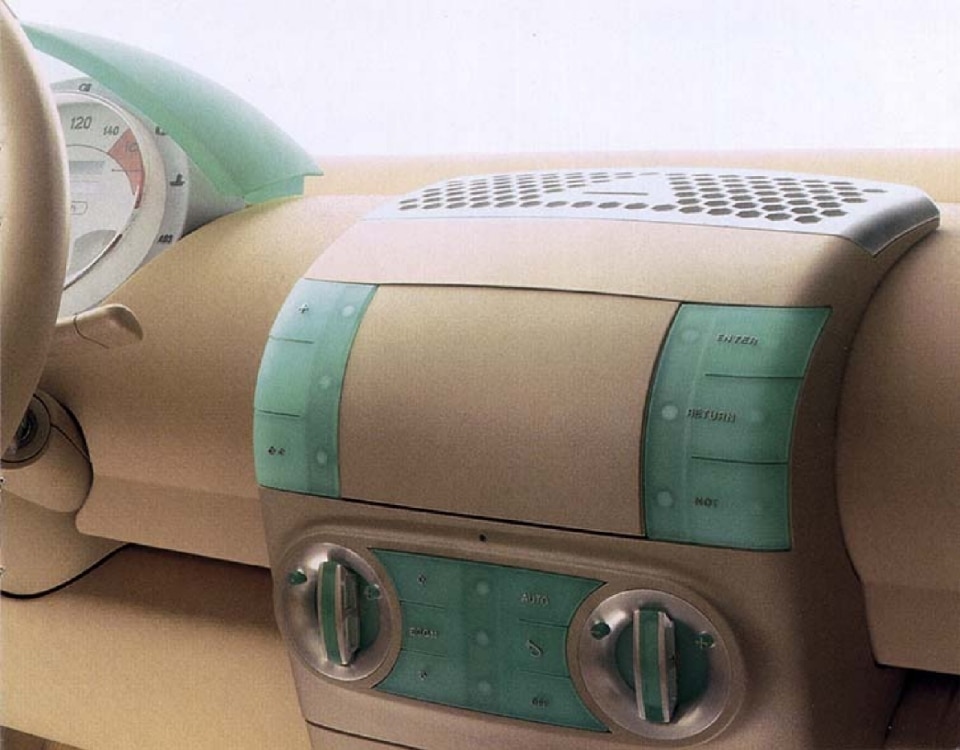

The result was a car with extreme, almost futuristic lines: less “car design” in the visual sense and closer to the rigor of a large-scale product design project. Surfaces flowed continuously, minimalism reigned, and a teardrop-like sinuosity cut through the air.

With a bold promise, to travel from Munich to Milan on a single tank, the challenging life of the A2 began. High costs made it an elite product. But in that very choice, defining it implicitly as a “designer car,” lay its uniqueness: Audi understood that the strength of the project was not just in performance, but in the details, the technical sand formal solutions.

Looking back, the A2 seems to have been born too early, perhaps with too much ambition, an attempt to teach us a lesson in sustainability and efficiency for which we were not yet ready.

A designer’s car, according to designers

We asked designers, owners or longtime admirers of the A2, to tell us about it in their own words, 25 years on.

Matali Crasset, internationally acclaimed and educated between Paris and Milan during that period, still owns an Audi A2. “My first car was a Twingo,” she recalls. “When my second child was born, the Twingo with child seats became cramped and impractical, as it was a two-door. My friends Patrick Elouarghi and Philippe Chapelet, founders of HI Hôtel and collaborators on many projects with me, were parting with their Audi A2, and we bought it second-hand in 2003. It’s still my car, twenty years later.”

Its compact form, non-statutory design, and refusal to follow the virilistic codes of car culture are the formal and design elements I find most interesting.

Matali Crasset

Crasset reflects on its commercial failure, questioning whether it revealed more about the outdated mindset of the automotive world. “The A2 is above all a lightweight car, not as light as a 2CV or a Renault 4, but under 900 kg thanks to its aluminum construction. This way of thinking about a car clashes with today’s SUVs and the ‘car obesity’ trend. Its compact form, non-statutory design, and refusal to follow the virilistic codes of car culture are the formal and design elements I find most interesting.”

For her, the A2 represents an era: “No exaggeratiopn, it’s a car I find hard to part with. Today’s car design doesn’t interest me: vehicles are too large, heavy, tall, ‘statutory,’ full of gadgets, and increasingly dangerous for pedestrians and cyclists. We need objects that are light, durable, sustainable, agile. In that sense, the A2’s greatest merit lies in qualities that are now almost entirely absent from the automotive market.”

Andrea Morgante, architect and designer known for projects like the Enzo Ferrari Museum, recalls his first encounter with the car: “July 2002: I was working at Future Systems and I remember seeing an A2 glide gracefully into our parking lot. Impossible not to notice: it looked like a tiny silver spaceship on wheels. Ross Lovegrove was driving, giving a ride to a Japanese journalist who had come to interview Jan Kaplicky.”

Morgante later left Future Systems after eight years to collaborate with Lovegrove. “At his legendary Notting Hill studio, Ross had created a ‘bespoke’ niche to park his A2 inside, separated by a wide glass partition. It was always on display, alongside his prototypes; in a way, it was deliberately part of the collection of extraordinary objects in his atelier. Ross has always pursued efficiency, lightness, and an organic language shaped by technology. The A2, being fully aluminum, was in some sense the automotive expression of his thinking. Even today, when Ross visits my studio in Notting Hill, we always end up talking about our A2s.”

Such technological complexity is unthinkable today for a car of this size. Not least, the incredible flexibility and modularity of the interior allow countless configurations. Joe Colombo would have loved it too.

Andrea Morgante

When asked what excites him about this often-controversial car, he replies, “Object, exactly! A design object first, a vehicle second.” He frames it as a love story with aluminum and lightness: “My first design object was an aluminum armchair. Later, at the Enzo Ferrari Museum in Modena, we created a 3,500-square-meter 3D aluminum canopy. Perhaps it was destiny. Sustainability and efficiency, values dear to architects, are still evident in the A2: 25 years later, it remains astonishingly contemporary in fuel economy, design, and aerodynamics. And it’s 95% recyclable.”

What fascinates him even more is the semiotic and aesthetic approach: “It escapes the pressure to shape every car according to macho-aggressive codes, favoring a rationalist, calm language where form follows function. That’s why many associate the A2’s design with the Bauhaus.”

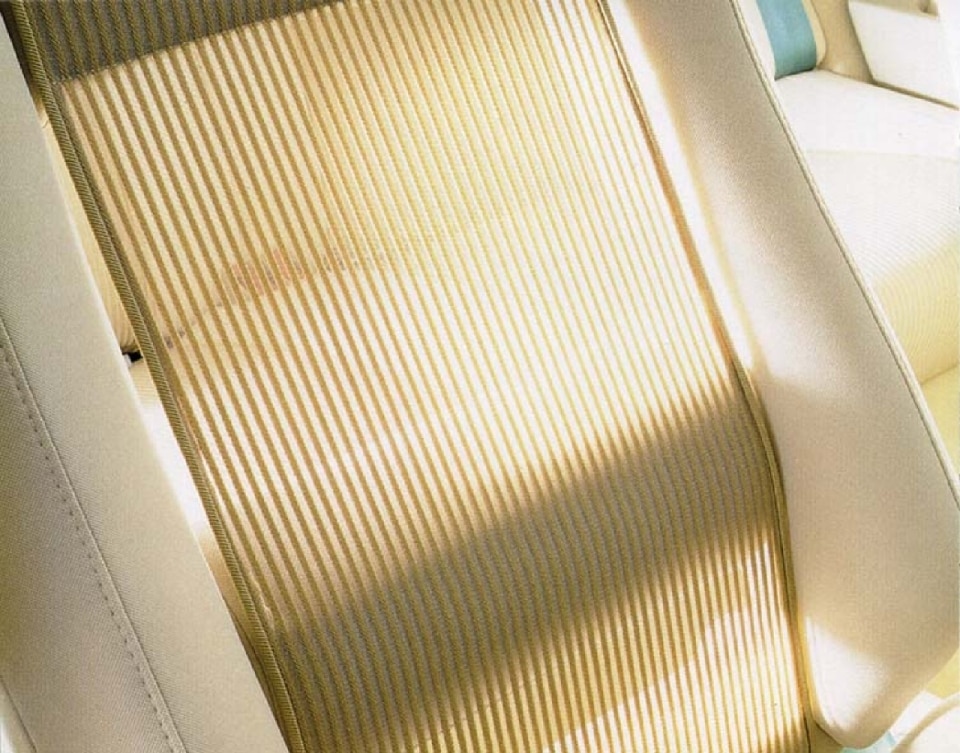

Morgante continues: “Beauty is often hidden and must be sought beneath the surface: lift the interior floor panels and you discover the refined aluminum sheets beneath. A technological rationality and composure more reminiscent of Dieter Rams or aeronautical construction. My A2 also features the Open Sky System, a fully opening panoramic glass roof, giving the cabin almost architectural brightness. Such technological complexity is unthinkable today for a car of this size. Not least, the incredible flexibility and modularity of the interior allow countless configurations. Joe Colombo would have loved it too.”

Opening image: ©Audi MediaCenter