Born in 1920 – just a few years older than other Neapolitan architects and designers like Eduardo Vittoria (1923), Filippo Alison (1930), and Riccardo Dalisi (1931) – Roberto Mango emerged as a progenitor for a generation of Neapolitan designers. Shaped by the post–World War II climate and the arduous task of reconstruction, these designers prioritized essentiality and the fulfillment of basic needs. Yet, they also believed that everyday objects should be not only functional but also beautiful.

An educated and refined designer, Mango lectured at prestigious American universities such as Harvard, Columbia, and Princeton. He served as the U.S. correspondent for Gio Ponti’s Domus, collaborated with leading companies like Arflex, Tecno, Poltronova, and Gavina, and created iconic pieces such as the “Sunflowers Chair” and an armchair for Ferragamo’s store in Piazza dei Martiri, Naples, Italy. Mango was a key figure during a pivotal period in Italian financial and cultural history, a time when the country shifted from applied arts to design while reviving traditional craft techniques. Within this diverse body of work, his extruded ceramic objects – produced between 1954 and 1955 for S.A.V. di Bellavista, a historic Neapolitan ceramics factory renowned for its Capodimonte porcelain – hold a particularly prominent place.

Mango goes beyond the urgency of post-war reconstruction and the anxiety of resource scarcity. One can already feel the creative energy that will soon erupt in Italy during a “boom” that will be not only economic.

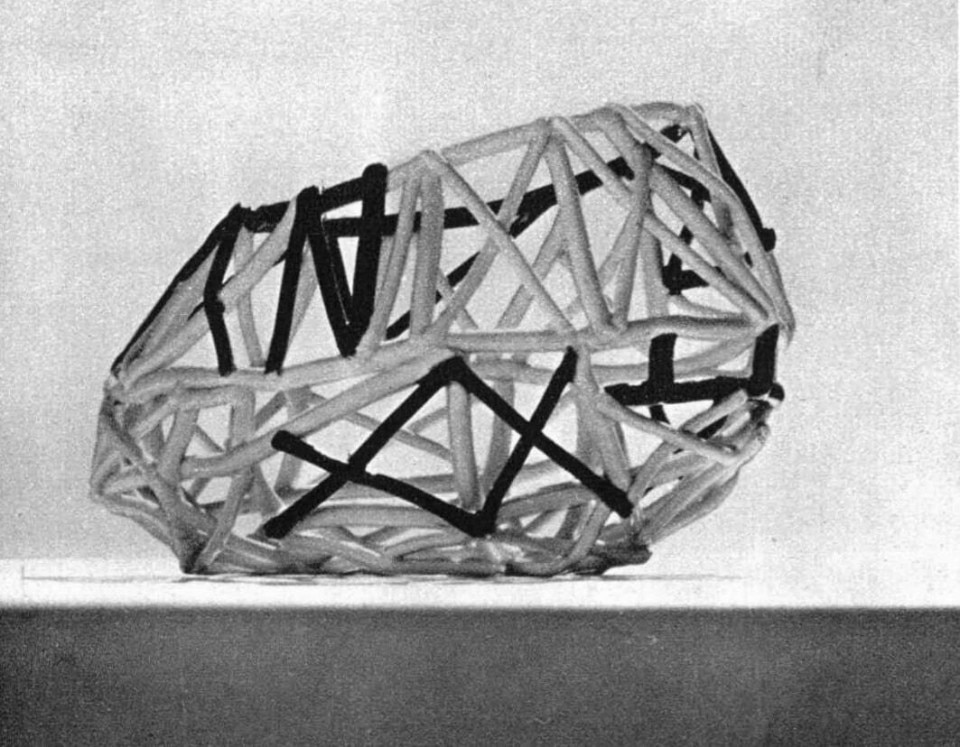

Mango designed trays, fruit bowls, lamp cups, and candlesticks, all crafted using a unique technique: drawing patterns solely with “spaghetti” of extruded stoneware, averaging about 5 mm in thickness. While ceramicists were already familiar with weaving these “spaghetti” strands like wicker for traditional baskets, Mango reimagined the method altogether. He addressed the technical challenge of using these extruded strands in a load-bearing capacity, fashioning them into light trellises and threadlike structures.

Moreover, Mango harnessed this traditional technique to create an entirely new imaginary and a new “vision.” The interplay of warp and weft in his work gives rise to fantastical objects that, while retaining the basic forms – such as plates, fruit bowls, or centerpieces – are transformed and presented as unfinished, irregular, and even anomalous. Most importantly, they can be customized by the individual craftsman through acceptable variations within a set framework of rules.

This recurring motif of interwoven textures is a recurring pattern throughout Mango’s designs. It can be seen in the woven ropes of his metal chairs, the circular pantograph fence designed for children, in textile prints for the Jsa Trienniale International Competition, and even in his studies of the application of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome concepts to understand the biology of universal structure and the forces of the cosmos. In his extruded ceramics, these tensions emerge as soft, plastic, malleable forms that yield surprisingly innovative shapes.

Mango’s approach was undoubtedly ahead of its time. Over seventy years ago, he developed a method that steered clear of the production of endlessly replicable, identical objects in favor of pieces that embrace the potential for ever-changing forms – all without sacrificing their identity and recognizability.

In short, his process was fluid and dynamic, inviting craftsmen to become the designers’ active collaborators rather than mere executors. In doing so, Mango anticipated later developments in series customization – an area in which Gaetano Pesce would become a prominent figure – as well as Enzo Mari’s 1970s A Proposal for Handmade Porcelain, which owes much to Mango’s methodological and formal innovations.

Undoubtedly ahead of its time, over seventy years ago, Mango developed a method that steered clear of the production of endlessly replicable.

What truly distinguishes Mango’s everyday objects – and their ability to transform ceramics into unprecedented, surprising forms, sometimes reminiscent of lace, other times of woven wicker – is not merely a formal originality that transcends the venerable traditions of Naples’ most renowned ceramic factories (Capodimonte, Giustiniani, Stingo). It is the force with which he liberates craftsmanship from its traditional role of merely satisfying basic needs. Mango goes beyond the urgency of post-war reconstruction and the anxiety of resource scarcity, infusing his exploration of local excellence with a global vision, in which one can already feel the pulsating, breathing creative energy that will soon erupt in Italy during a “boom” that will be not only economic but also profoundly social and cultural.

Opening image: Domus 296, July 1954