LagosPhoto, the international photography festival launched in Nigeria in 2010, is reinventing itself: changing format, perspective, and even curator. Starting with the next edition, it will become a citywide biennial, bringing photography into symbolic sites across Lagos. From October 25 to November 29, 2025, disused prisons, independence-era palaces, and radical architecture will be transformed into stages where photography interrogates the concept of incarceration. Leading the project is architect and curator Courage Dzidula Kpodo.

“I joined the team earlier this year as principal curator,” he says. “It all started with my previous project, Postbox Ghana, and the idea of installing large billboards in public space. Stepping outside the white cube was also the starting point for my work here.”

If you asked an average person, ‘What is freedom to you?’ you would surely get an answer. But the real question is, ‘Do you truly believe that answer comes from your own will?’

Courage Dzidula Kpodo

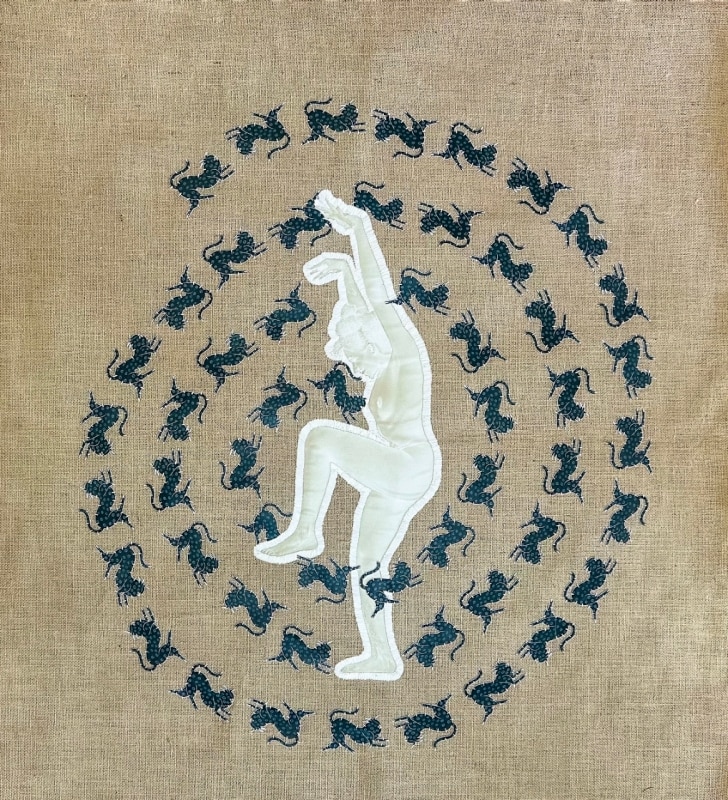

The theme chosen for this edition is Incarceration, understood not only as a material condition but also as an inner dimension. Kpodo stresses that not all forms of limitation are visible: some relate to migration and borders, others are more subtle, internalized in daily life. “Migration is a big theme. And when you think of migration, you think of borders. Borders themselves are a form of incarceration, evolved through different histories. In Europe they follow defined ethnic lines, while in West Africa they cut across them, creating conditions we still have to deal with today.”

But it is not only about borders. The reflection extends to a critique of the false sense of freedom that shapes many contemporary conditions: “Think of the 9-to-5 work routine, aimed at owning a home but without really enjoying it. For a long time we believed it embodied freedom, but now we realize it may, in fact, be a form of self-incarceration.”

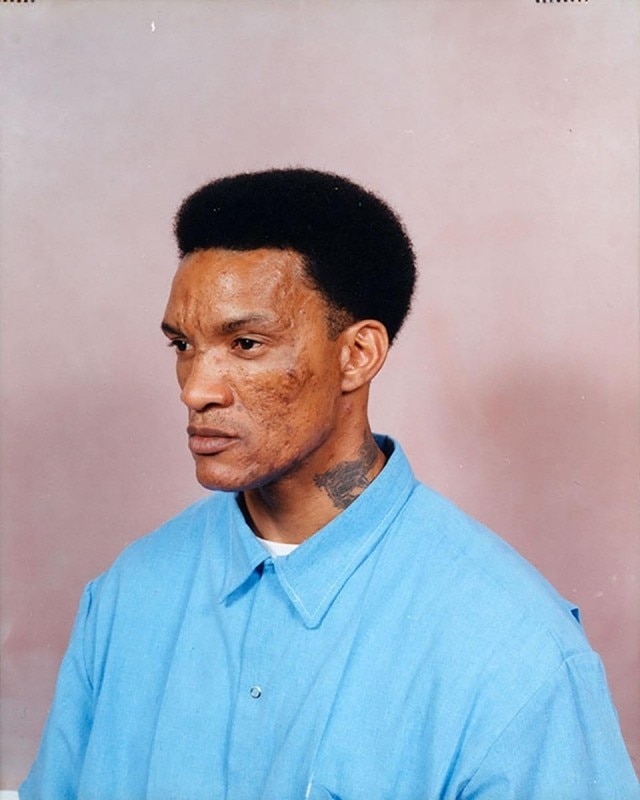

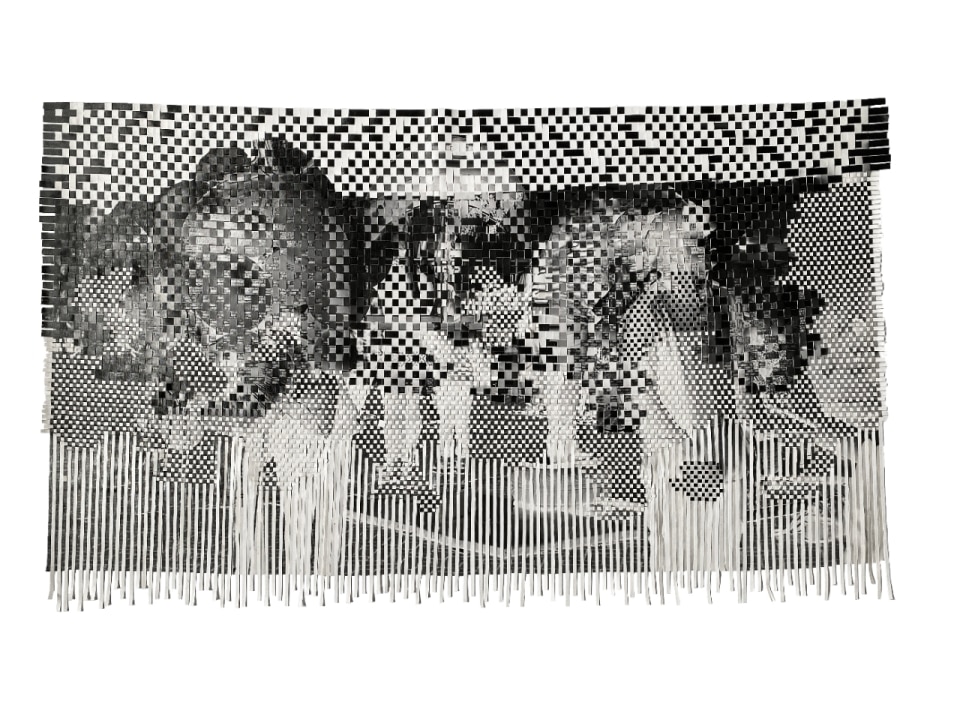

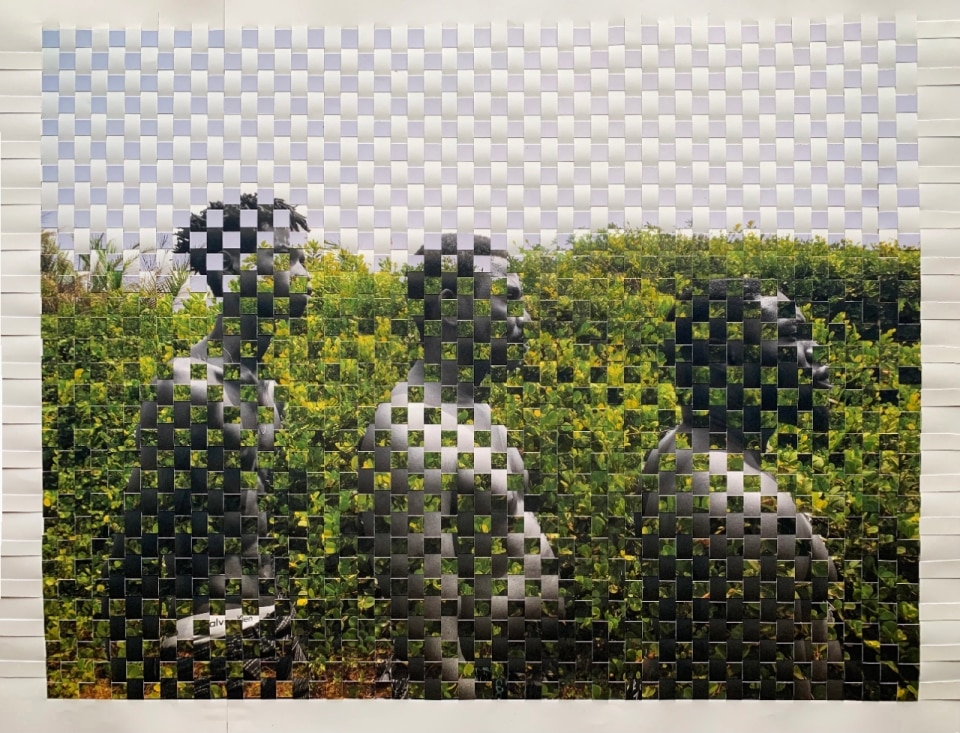

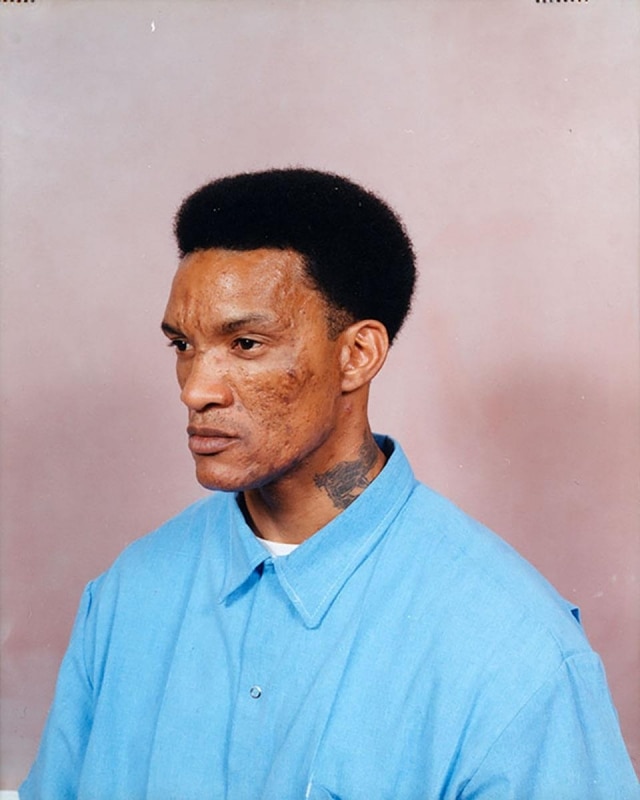

For Kpodo, photography becomes a tool to break through illusory patterns. Among the featured artists he points to Kanya Zibaya, who addresses the historical violence of apartheid in South Africa not by accusing the colonizer but by turning the question inward. “Working with archival materials, he asks: how have we internalized this violence, continuing to perpetuate it even after those systems have been formally abolished?”

It is easy to fall into a mental pattern, conditioned either by oneself or by external factors. This edition, then, is ultimately a reflection pointing towards freedom.

Courage Dzidula Kpodo

Even the move to the biennial format is not just a technical adjustment but a methodological choice. “It allows us to slow down, experiment, and work with alternative spaces that already carry stories of their own.” Hence the choice of sites such as Freedom Park, a former British colonial prison now transformed into a public park, or the Nahous Gallery inside the Federal Palace—the building where the Declaration of Independence was signed, closed for decades and now reopened as a cultural center. For the first time, the festival also expands to Ibadan, to the New Culture Studio by Demas Nwoko, the architect and artist who as early as the 1970s envisioned community-based and experimental architecture.

“My hope is that this exhibition will make people reflect on the relationship between art and space. I don’t think they should be separated: the neutral white cube model is no longer enough. I believe art must engage with places—even abandoned ones—and with the people who inhabit them.”

The biennial format makes it possible to slow down, to experiment, and to work with alternative spaces that already carry their own histories.

Courage Dzidula Kpodo

His sensitivity to places comes directly from his background. “I am an architect myself: I studied in Ghana and have just completed my master’s degree at MIT. Perhaps that is why, in curating this Biennial, I paid close attention not only to the structural dimension but also to the symbolic value of the sites.”

And when asked about the future of the festival, Kpodo is clear: it must remain a ground for experimentation. “In West Africa we are in a unique position: technology is widespread and rapidly evolving, yet still fluid, not crystallized. I hope more and more people will have the courage to use it in radical ways—bringing art and space to the people, rather than forcing people to go to them. This, I believe, is the most important step to take.”