Fear is “an emotional state consisting of a sense of insecurity, bewilderment, and anxiety when faced with a real or imaginary danger or what is (believed) to be harmful. It can be more or less intense, depending on people and circumstances, and it becomes a strong and sudden disturbance, which also manifests itself with physical reactions, when the danger arises unexpectedly, takes you by surprise, or appears imminent” (from the Treccani).

Fear is a feeling that connects us all. It is a feeling of apprehension that we have been experiencing for months because of this absurd and devastating pandemic.

It is a fear of the future, a fear of not making it, a fear for everything that will or might happen.

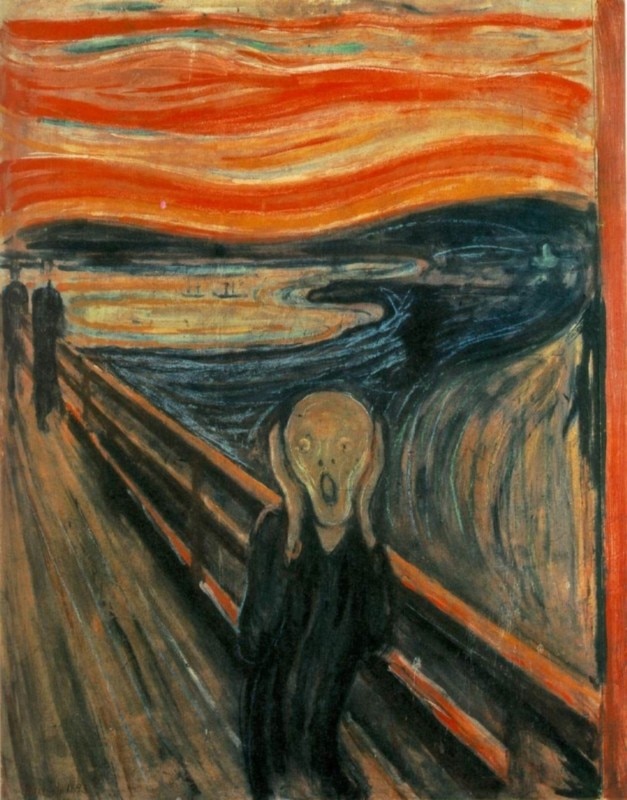

In art, the fears of our ancestors were represented by Griffins, Chimaeras, Gorgons, Centaurs, Sirens, Satyrs, Harpies, Sphinxes, Minotaurs, and many other characters from the classical tradition. The representations of evil, fixed figures of the psyche, were extremely varied and influenced various artistic representations – sculptures, terracotta pots, pottery, medieval frescoes, and mosaics or even Gothic cathedrals, paintings of the classical period, such as Caravaggio’s Head of Medusa, or more contemporary paintings such as Munch’s The Scream.

The philosopher Umberto Galimberti once said: “Fear, in fact, is an excellent defense mechanism, because we are faced with a specific subject. Fear is not only negative, because we are here in the world, and we can live thanks to our fears” and added, “Fear is rational, anguish is not”. Over the centuries, works of extraordinary beauty have translated this feeling through multiple subjects or different narratives – which is a way, perhaps, to exorcise fear, and to fight it.

A monster with the face of a woman whose hair has turned into snakes that petrify anyone who dares to look at her – Medusa. The one described by Caravaggio is perhaps the most famous representation.

It was made in 1596 and commissioned by Cardinal del Monte to pay homage to Ferdinando I de Medici. The Medicis considered it to be a good omen, as well as of high apotropaic value. Here, we see Medusa’s head being cut off by Perseus’ sword. Her eyes are wide open and full of terror, the mouth is open as well in a scream of pain. The realism in the painting is typical of this great artist who decided, through the myth, to address the theme of fear and pain, thus stigmatizing these two feelings. Medusa was painted on a shield, a typical warlike instrument of defense, in order to glorify the Medicis, for the strength and power they showed while governing their city, always paying close attention to justice and democracy.

At the Berlin Secession exhibition of 1902, Munch placed his works on the four walls of the entrance hall so that they could form The Frieze of Life series, and hung two other works on the wall dedicated to the Terror of Life: Anxiety and The Scream. “I was walking along a path with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

His most famous and emotional work is a synthesis of what the artist was and felt. It is a work with a strong psychological content, an exact summary not only of the painter’s life but of the life of every man. In all his works, Munch gave space to his emotions, giving priority to the subjective and completely neglecting the objective. He dealt with existential themes such as anguish, fear, melancholy – all emotions that he experienced. His is an emblematic abstraction, and his quick, thick brushstrokes maintained a monochromaticity of both cold and warm colors, which he chose depending on the emotions he wanted to represent. “You may not recognize me, but I am that man. [...] The whole scene seems unreal, but I would like you to understand that I lived those moments. [...] Through art, I try to see my relationship with the world more clearly, and if possible, I try to help those who observe my works to understand them, and to look inside themselves”.

Opening image: Shield with Medusa head, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1598, Uffizi Museum, Florence, Italy