It’s impossible to understand the paintings of Balthus without understanding his biography: the painter, born an aristocrat as Balthasar Kłossowski de Rola (Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001), had a unique life – his encounters with other figures of the time would be enough alone to delineate twentieth-century European culture, which is expressed in Balthus’s art in a rich and lucid synthesis. The exhibition Balthus, curated by Raphaël Bouvier and Michiko Kono, summarises his life and unique perspective in 40 works – all important, even fundamental in the artist’s career – with an exhibition design that makes skilful use of the language of colour to highlight the themes and the atmosphere of the paintings.

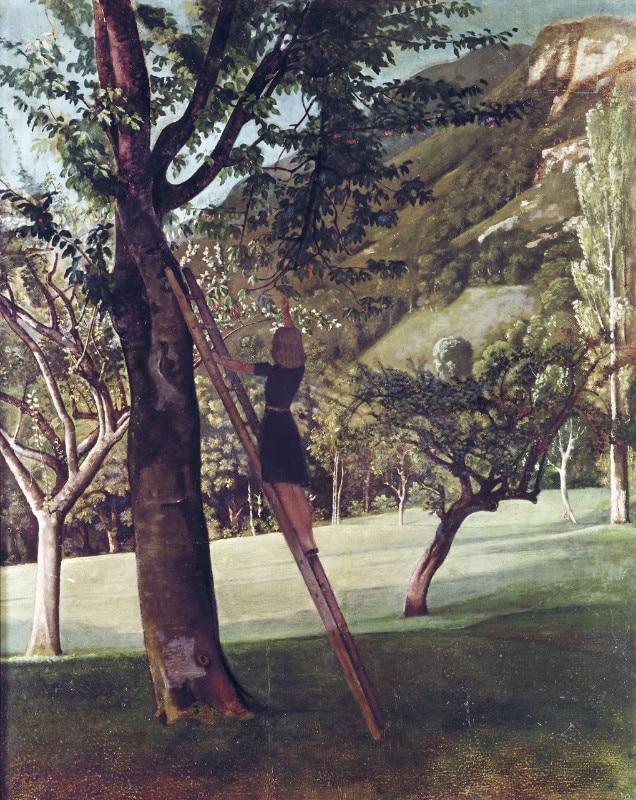

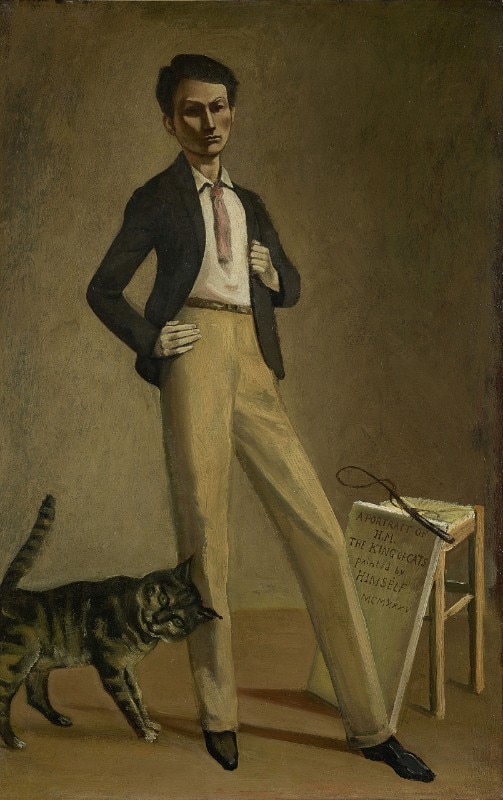

A precocious talent, in 1919, when he was just eleven years old, he created an illustrated story entitled Mitsou which recounted the tale of a little boy and his cat, who eventually disappears. The book was published two years later, with a preface by the great poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who was involved with the painter’s mother. Rilke was one of many artists and intellectuals who crossed the painter’s path and enriched his life. A self-taught painter, Balthus learnt the secrets of composition and form by enthusiastic copying of the paintings of the great masters of fifteenth-century Italian art – from Paolo Uccello to Piero della Francesca, whose original works he copied in Arezzo, during his stay in Italy in the summer of 1926. He learnt to combine those models with lessons in colour and renewed expressive gesture taken from the works of Bonnard, Vuillard and Derain, painters he met frequently, thanks to his family’s position as part of the Paris cultural elite. Expressing this atmosphere and this idea of the world are some of the first canvases on show at the Beyeler Foundation, such as Orage au Luxembourg and Le Jardin du Luxembourg (L’Automne?), both painted in 1928. Today they appear almost like notes or sketches for his more famous later works – they already indicate a definite stance, one strongly pictorial, anti-avant-garde and absorbed in the contemplation of life.

Balthus had to wait until 1943 for his first exhibition (in Paris, at Pierre Leob’s gallery). There he put on show – though without commercial success – the results of his intense initial years of work. To that period, decisive too for the definition of his themes and approach, belong works such as Pierre et Betty Leyris and the other key painting from 1933, La Rue, which perfectly links the erotic and temporal dimensions: the bodies and gestures are immortalised in the kind of frozen moment that would become a stylistic and conceptual hallmark of Balthus’s work. In Pierre et Betty Leyris, the appearance of the female body is offered completely to the gaze in an eternal, though very fragile moment. In La Rue, the movements and human actions are crystallised and projected onto an eternal dimension – that “duration outside of time” that the poet and critic Yves Bonnefoy called the “realism of the improbable”.

Painting is a language that cannot be replaced by another language

Though something similar had already been expressed by Metaphysical art, Balthus pulled into this immobility a pulsating erotic presence, as well as a subtle but vibrant vein of humour, one totally absent in the work of artists such as De Chirico, and probably the product of Balthus’s love for illustrations in children’s books. However disappointing the results of the Leob gallery exhibition, leading intellectuals and artists such as Breton and Picasso immediately recognised the importance of the work. Picasso bought one of Balthus’s masterpieces, Les Enfants Blanchard (1937), which remained a part of the Spanish painter’s collection throughout his life. Just a year later, Pierre Matisse exhibited Balthus’s paintings in New York, bringing him the recognition that led to exhibitions and retrospectives around the world.

A long, careful look at the works on show reveals the elements that create an entire world in each of them, one self-sufficient and contained within the boundaries of perfectly calibrated spaces. Thérèse rêvant (1938), for example, one of his most famous and disturbing works, lets us trace subtly complex influences that touch unaffectedly on the whole history of Western art. Below the meticulous and unperturbable realism, however, lie insidious, hallucinatory and unsettling depths pointing both thematically and formally to a surrealist soul that, though concealed, remains active – like an ember still glowing under the ashes.

Reality and figuration always remained central to Balthus, who throughout his life flirted with the avant-garde in all its forms but never let himself be seduced by the dogma of modernism. Rather, as he said, “Painting is a language that cannot be replaced by another language.” It had to remain an alphabet of recognisable signs: “I will always find even the worst paintings that attempt some kind of representation better than the best invented paintings.”

Reality and figuration always remained central to Balthus, who throughout his life flirted with the avant-garde in all its forms but never let himself be seduced by the dogma of modernism

As already mentioned, Balthus made his artistic debut as a child with the illustrations for Mitsou. The artist was the supreme painter of the relationship between human and cat (equalled perhaps only by Leonor Fini). This fetish animal is evoked again and again with strongly ambiguous identification (Le Chat au miroir III, 1989-94): it represents that silent, morbid life at home to which the cat is a witness, sudden playfulness but also diabolical lust, as in paintings such as Thérèse rêvant. The artist took refuge in Switzerland during the Second World War and an extraordinary clarity, luminous transparency and superhuman tranquillity characterise the works painted there – for example, Paysage de Champrovent (1941-43/1945). The scene is radically different from the conflict of the time – the feeling is one of a lack of air, a lack of atmosphere. It is a supreme expression of that incorruptibility of which Balthus was the greatest exponent.

- Exhibition title:

- Balthus

- Exhibition dates:

- 2 September 2018 – 1 January 2019

- Curated by:

- Raphaël Bouvier, Michiko Kono

- Venue:

- Fondation Beyeler

- Address:

- Baselstrasse 101, 4125 Basel, Switzerland