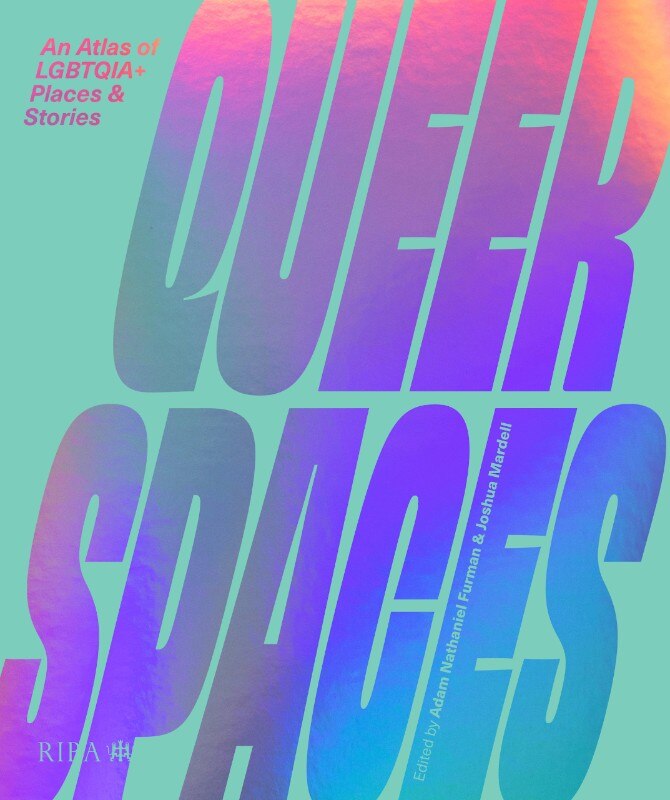

Internationally renowned designer and artist Adam Nathaniel Furman recently published an atlas of 90 LGBT+ spaces from around the world in collaboration with architectural historian Joshua Mardell. Bringing together in its pages a community of contributors capable of defying cis-heteronormative morality even in spatial terms, Queer Spaces: An Atlas of LGBTQIA+ Places and Stories is a book about community and affection, even before the formal necessities of space.

“The book is the result of a journey that started a long time ago with my university experience,” Adam tells us during a long talk. “At that time, I felt the need to express my identity and homosexuality, even in projects, but faced constant humiliation. In order to stay afloat, I tried to frame my work within issues that were fashionable at the time or that people in academia were interested in. And when I finally got into spaces where people were asking me to share me and my work freely, it turned out that I was apparently the only designer who managed to get by pushing identity through visual culture in my design, always in an unostentatious and very aggressive way. From there, strangely enough, many people started to turn to me as a reference point. I was invited to Berkeley and Harvard for lectures – again by students, but by professors –, and after the experience of a paper for Architectural Review I was called by RIBA Publishing in 2017 to write a book on postmodernism (Revisiting Postmodernism, Adam Nathaniel Furman and Terry Farrell, 2017).”

View gallery

View gallery

“At RIBA Publishing there has recently been a team change, with Helen Castle as the new Editorial Director, the first woman editor with a desire to shake things up and do new things. Any other publisher would not have done the book. It would not fit into any category. It might look like a coffee table, and maybe it is, but not only that”.

The book, on bookshop shelves since last May, is an ambitious project in its most intimate sense. With a roundup of examples from vast and heterogeneous places, the pages tell the story of one of the many minorities that have always been excluded from the pages of academic bibliography. “Joshua and I continue to receive photos from students in the UK and Ireland who have the book open when showing their thesis project. In university circles, there is always a candidate who might refer to a theorist or an -ism or an architect. They put a doodle on the wall, and everyone would say, ‘Ah, this reminds me of the darkness in Japanese architecture or phrases like that. Queer students presenting their work had to invent their own language. But you cannot expect people to invent everything from scratch. This is a book published by the Royal Institute of British Architects, even the most senior lecturer cannot reject it,” Furman continues. “I’m not saying that the book will solve the problem, but just the fact that it has been publicly framed means that there is also a solution.”

I’m not saying that the book will solve the problem, but just the fact that it has been publicly framed means that there is also a solution

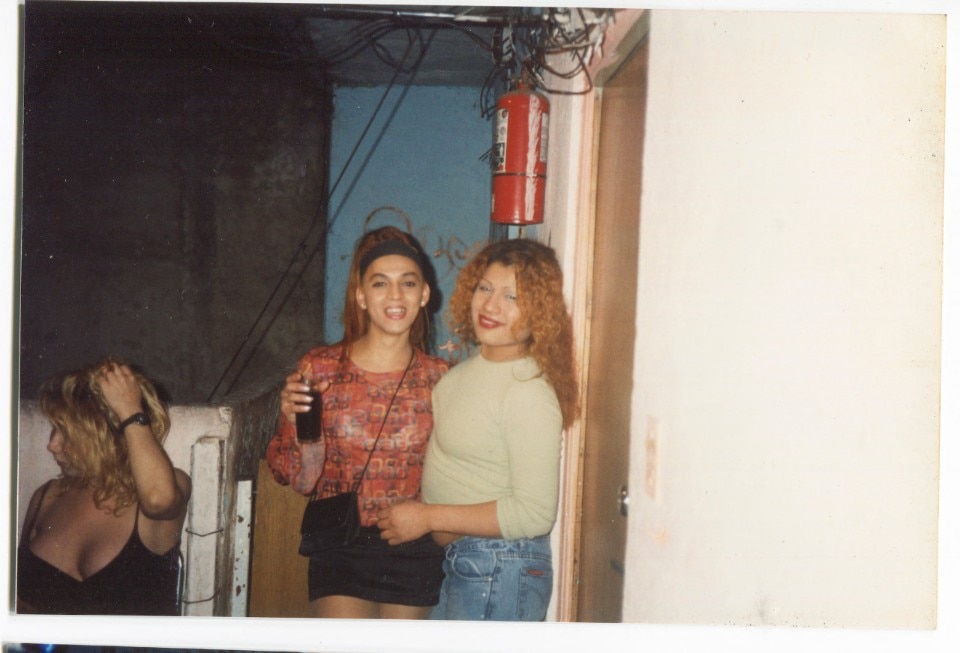

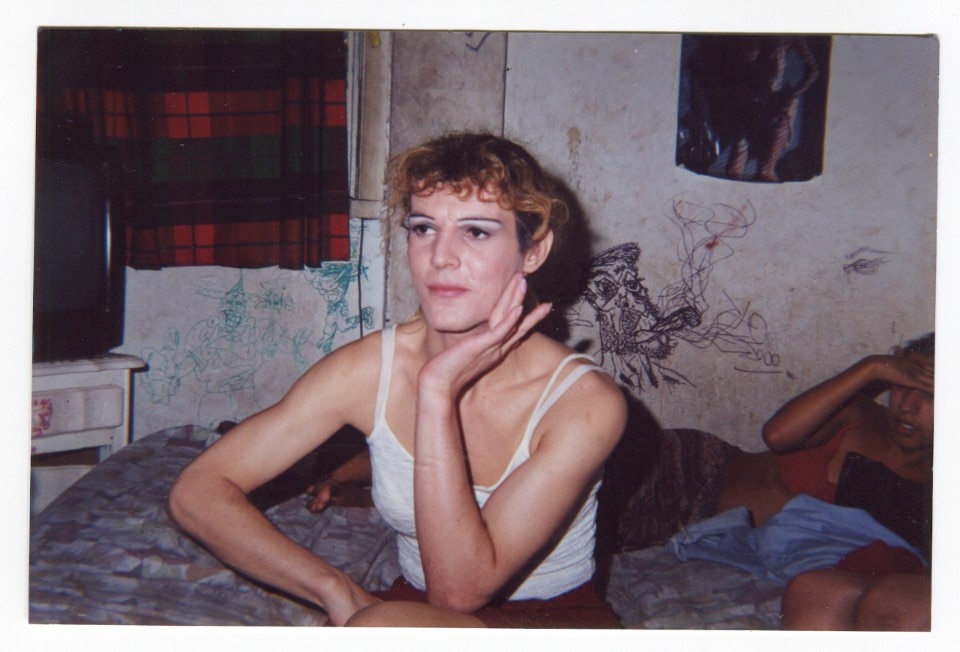

The 90 examples are collected in an encyclopedic way in three categories: domestic, small microcosms dealing with those whose lifestyles were forbidden in the public sphere; communal, community gathering and sharing spaces; public, manifestos of expression in the urban globe. “For the list of references, Josh and I used a mixed method of open calling and networking. For about six months, we contacted friends and colleagues but ended up with a too predictable list. So we embarked on this very long research journey from the best-known cultural centers to the smallest clubs. We got a lot of references that we could not include in the book for safety reasons because we would have endangered the people who live there. I would have liked to have more spaces in North Africa”.

And it is precisely in the spatial analysis that the security issue becomes central in projects dedicated to or transformed to house queer community nuclei. There are very few examples of places that are entirely open to the street front and the rest of the city, giving priority instead to the creation of an intimate nucleus where one can feel protected, often referred to with the connotation of safe space. But if the honest relationship with the outside world is conceivable and feasible, in Western-style metropolises, the same cannot be said for the rest of the world. “On the one hand, there are iconic examples like the Pride Centre in Melbourne. This huge government institution is open to all queer people, offering business start-up space, event space, and more. It is a spectacular piece of architecture, available to the public, open as if you were entering a library”. According to Furman, this is the example of a bulding that is almost post-queer, in the sense that it is completely open and safe.

The poignant or melancholy side of the queer story in terms of space is isolation

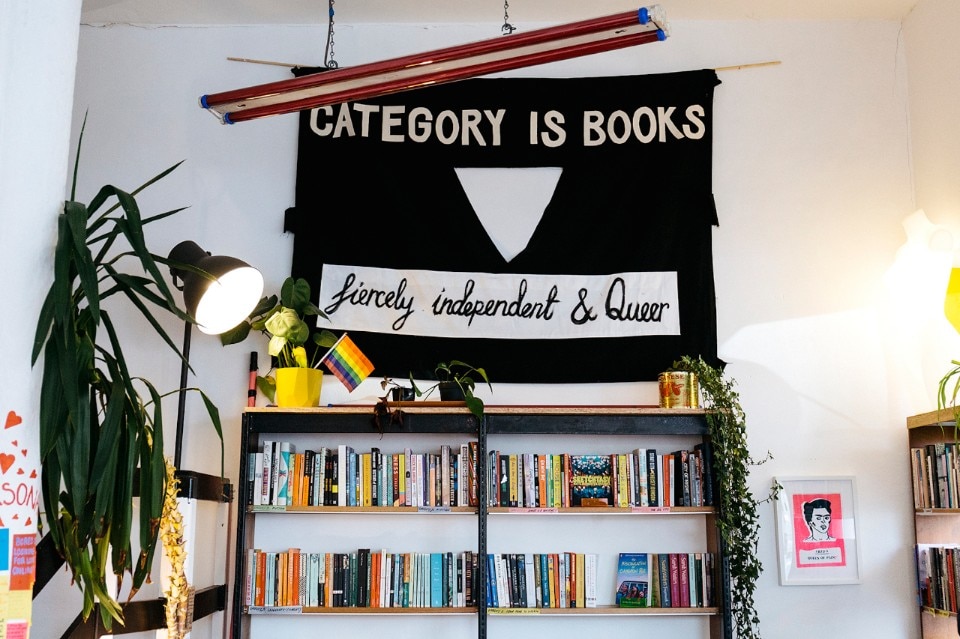

Certainly, virtual reality curbed the remoteness of community places and the lack of information significantly. Given also the experience of the last few years of pandemic isolation, socials like Tik-tok have become for the gen-z true meeting and sharing places. “Between real and virtual collective places, there is a complementarity. And I think there is a beautiful description of this in Bangkok’s Kloset Yuri Book Club, a kind of book club of lesbian women and gender-nonconforming people, which people who meet online use as a safe meeting place. It becomes a way to bring the digital into the physical because I think the physical is viscerally necessary. You need to help people. You need to touch people. You need to discuss. You need random people you meet while looking at a book. These things need to happen so that you don’t feel completely isolated and alone”.

The story of the humanity can be told through materials, expressed through textiles, in art as well as in architecture, not through spatial typologies that have been theorized for decades

But if, since their academic years, architecture students have been used to dealing with a particular language – a visual representation of the culture of a very narrow elite – what can we expect from the world of architecture in the coming decades of fervent queer revolution? And how will the profession itself change? “Freedom. The world of architecture is the most fascist environment I have ever experienced in my life. The story of the humanity can be told through materials, expressed through textiles, in art as well as in architecture, not through spatial typologies that have been theorized for decades or centuries. And this is a straightforward story to tell,” Furman concludes. “It can save us because the profession is a nightmare, it is made up of attitudes that are now fashionable and now miserable, starting from the way people are treated in the workplace to the fact that everyone, apart from a tiny minority, has to leave their identity at the door and cannot express themselves. And queerness is ambiguous. It is fluid. It is dynamic. It is impossible to define.”