The 1960s were the years of revolution, not only political and social, but also cultural. In Europe and the United States, architects experimented with new ways of practicing their discipline and inhabiting space, questioning the ideology and founding principles of the great protagonists of the Modern Movement. New projects arise. They no longer aimed at a traditional vision of architecture, but at thinking of domestic space as a space of life (be it a hut, an interior design, a villa or a pneumatic structure). Decades of design experimentation followed, not only in terms of form and construction, but also in terms of content.

Naturalised French architect Guy Rottier was born on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia. Born in 1922, he graduated in engineering in The Hague and then studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. During his stay in Paris, while working on the Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles (1947-49), he collaborated with Le Corbusier’s studio. Then he moved to Nice, where he founded his own firm with his brother François. Rottier spent much of his career experimenting with living, imagining flying holiday houses, tourist villages to be burnt down after use, “talking” architecture in the shape of snakes and snails.

Rottier brings us back to the points of connection between architecture and other disciplines (art in particular, but anthropology, sociology, philosophy as well), of utopian and dystopian visions of living, but above all of reconciliation between the design experience and that of everyday life, made up of experience, feelings and life.

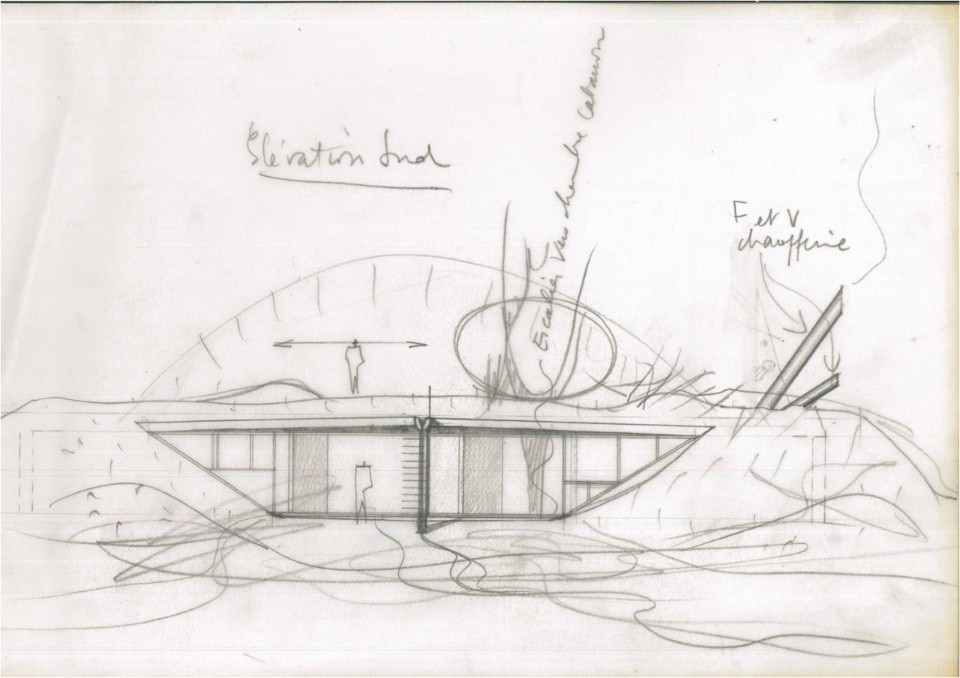

Built in 1968, the Villa Arman in Vence, is the most famous of his few works of architecture. Rottier is close to the world and to artists such as Ben, Arman himself and Yves Klein. In Nice, he also sympathises with the artists of the Nouvelle École de Nice, becoming its only member architect. His practice and his way of rendering projects on paper brought him closer to a pictorial dimension than an architectural one, as he always worked on technical drawings such as plans, elevations and sections which were more like paintings than technical drawings. The organicity of his buildings was also represented through plastic models with sculptural value, many of which are now on display at the Frac Centre in Orléans, France.

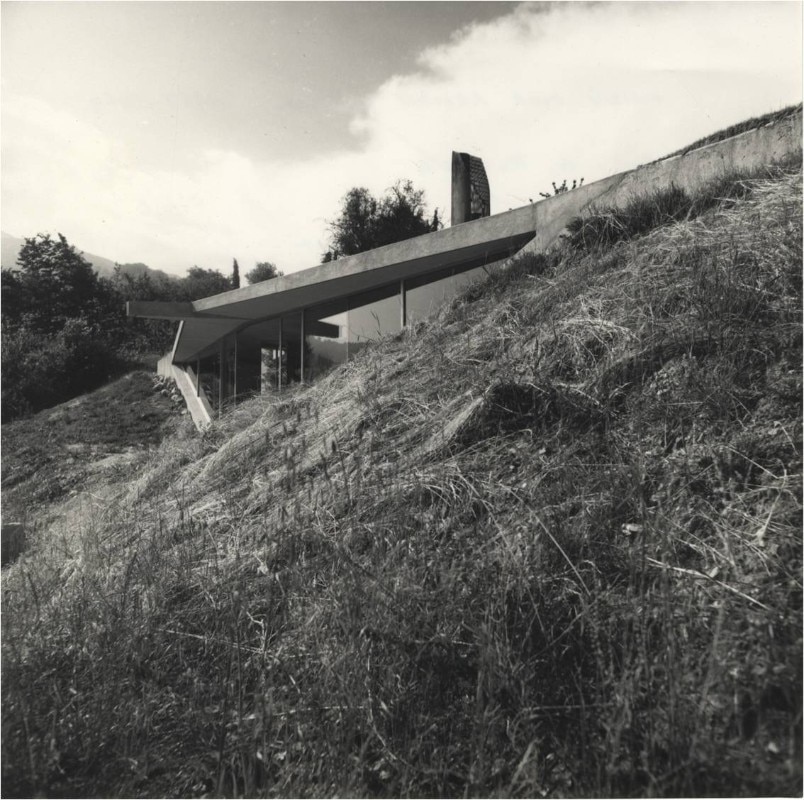

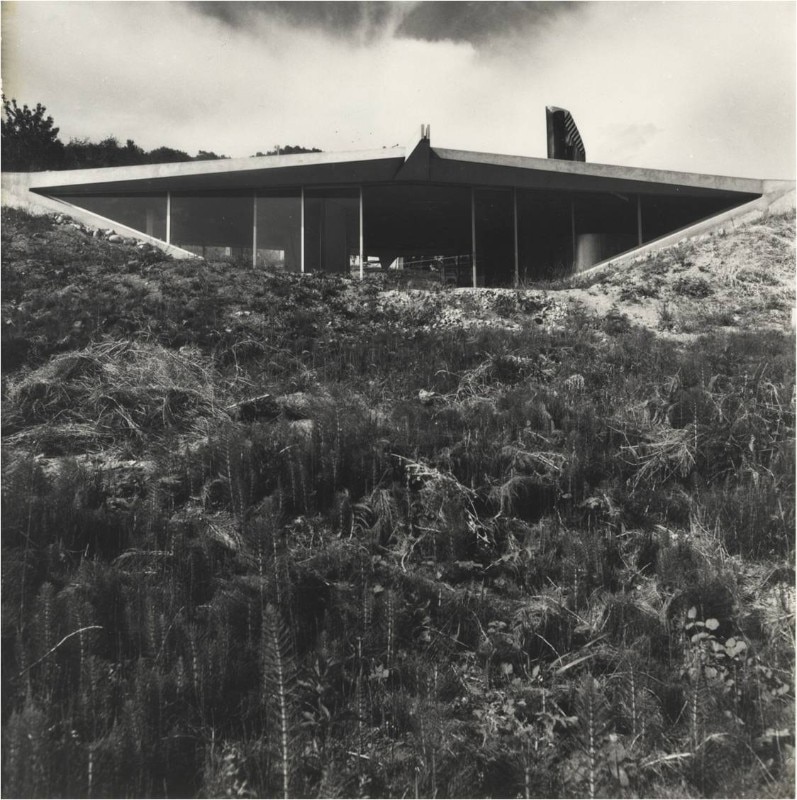

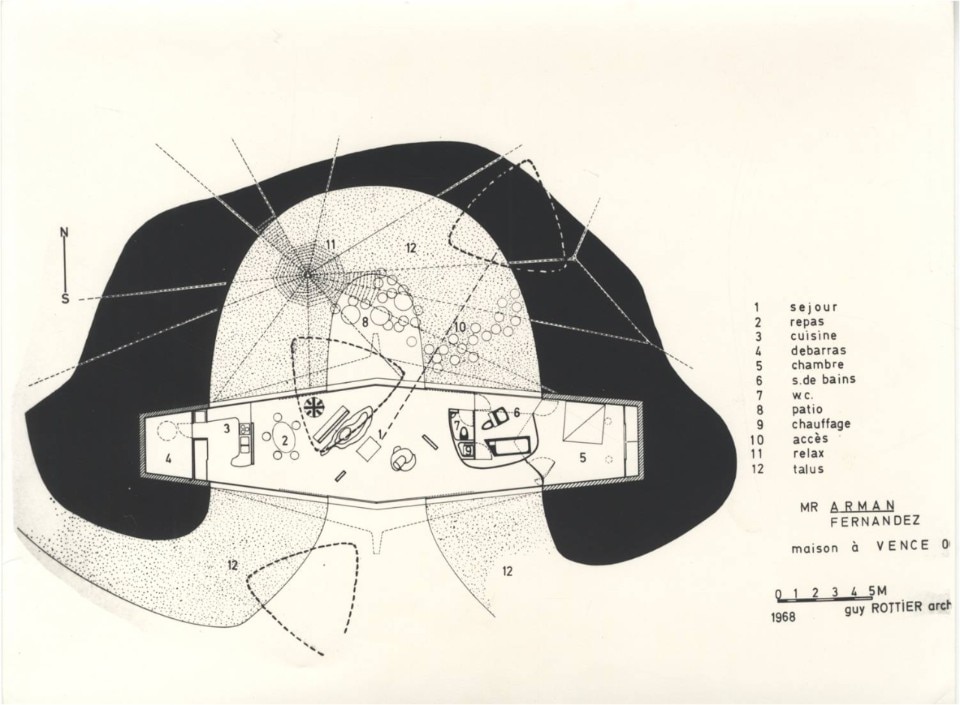

In the Villa Arman, Guy Rottier translates years of research on the mimetic house into a three-dimensional building. Dug into the ground and completely covered by soil, sand or stones, this type of dwelling is conceived as an organic whole emerging from the ground and relating to the surrounding space through the openings. Rottier dug out the site – with the technical support of structural engineer Marc Strazzieri – to create a sort of amphitheatre on the north side of the slope, forming a courtyard the house is entered through. The plan is laid out from east to west, so as to create a glass facade on the south side whose transparency allows the inhabitants to enjoy the landscape and the sea view.

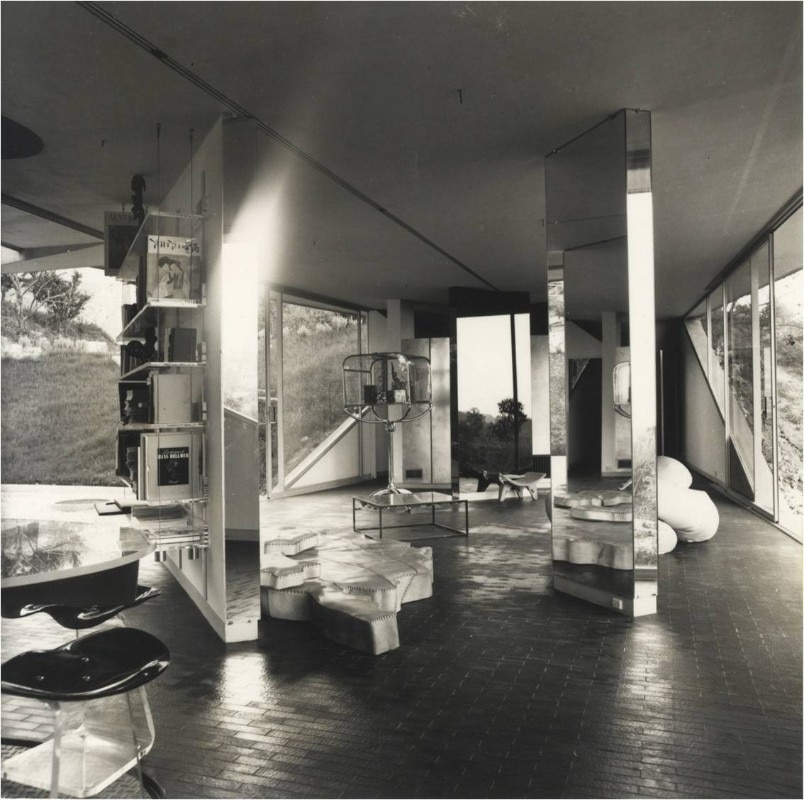

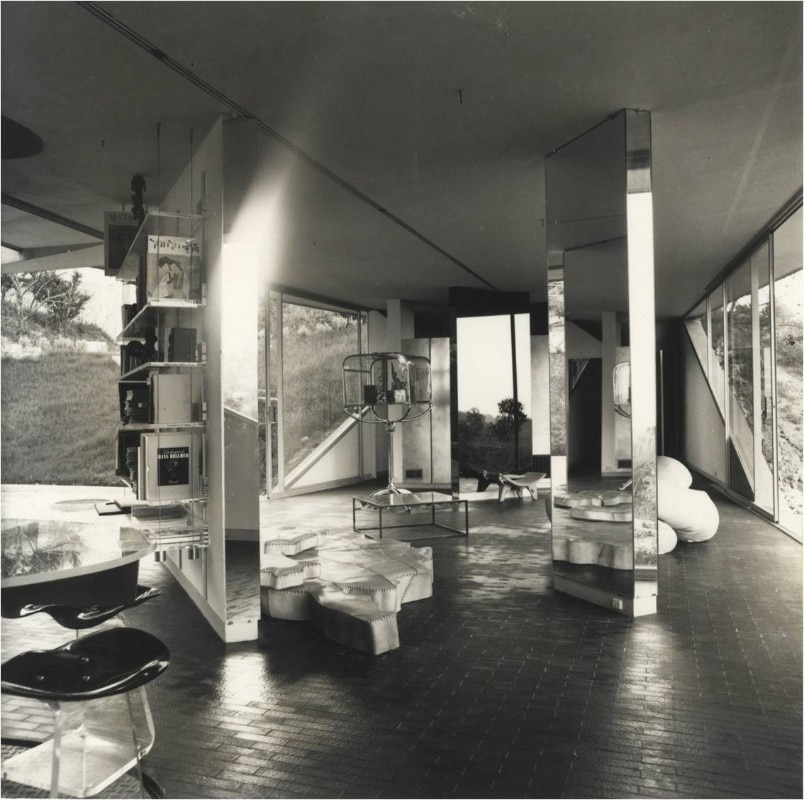

It consists of a living and dining room designed in the centre, a bedroom arranged at the end, and the kitchen and bathroom in the spaces in between. With the exception of the bathroom, the interior space is divided by oblique concrete walls. In fact, the bathroom is a self-contained circular volume, a stainless-steel sculpture. The connection with the outside is amplified by mirrored surfaces, inserted by Arman himself. A real installation that not only expands the space but also creates a perceptual confusion, desired by the artist, to break down the boundaries between inside and outside.

The house is equipped with solutions designed by Rottier himself. For instance, the living room table which retracts into the floor at the touch of a button. The original system of mobile polycarbonate capsules, each of which is triangular in shape and 20 square metres in size, intended to provide a bedroom and a small bathroom for guests, has never been built.

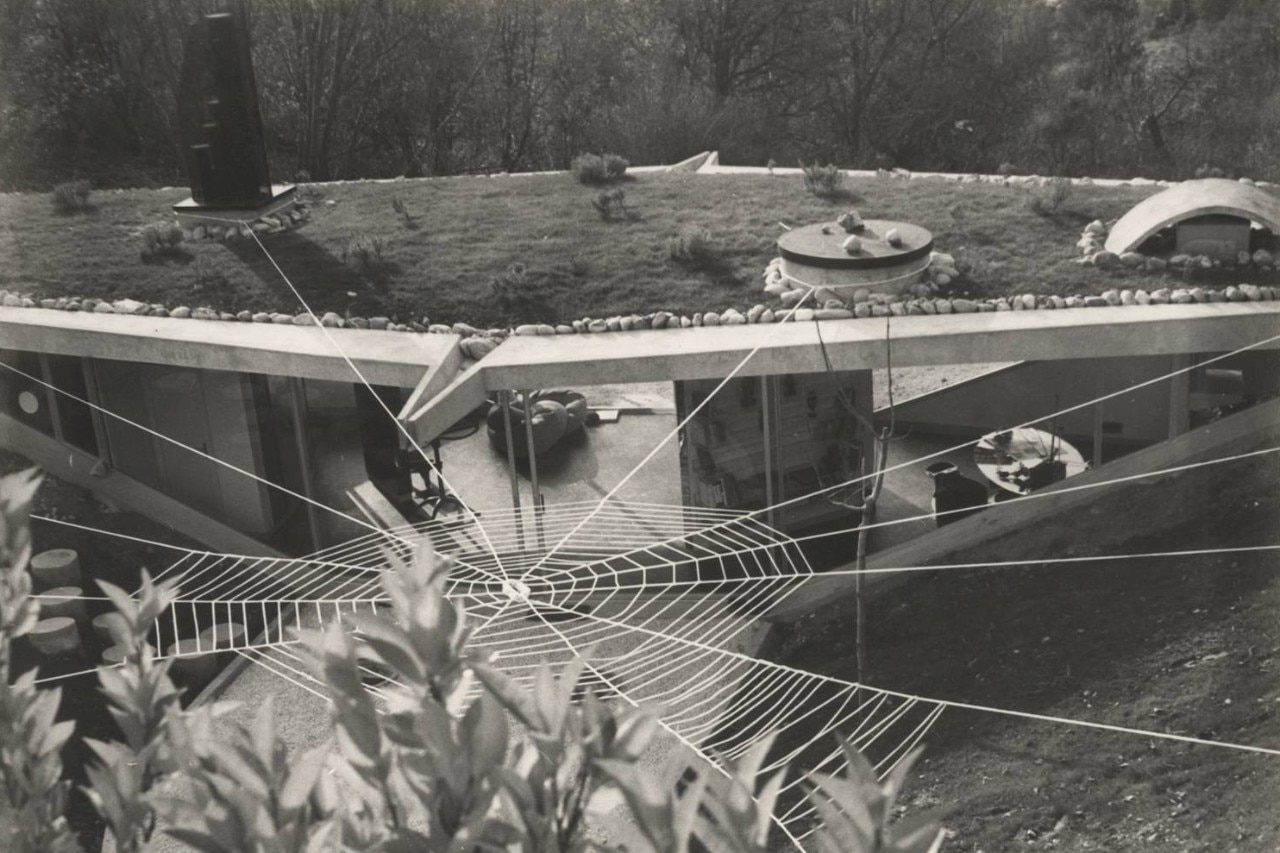

Outside, a “lumiduc” – a mirrored element to send daylight to an underground dwelling – illuminates Arman’s half-buried room for three hours a day. On the north side of the house, a spider web shaped hammock decorates the garden along with the oversized gargoyles on either side of the roof. Thanks to the underground position of the house, Rottier created a roof garden whose design is inspired by Japanese botanical culture and the Wabi-sabi founding principle of their architecture. The architect designed a walkway to the north of the house on large cylindrical concrete structures inspired by the paths marked out in gardens in Japan.