This article was originally published on Domus 1061, October 2021.

- Fabrizio Prati:

- Associate director of design, NACTO – Global Designing Cities Initiative

- Gideon Boie:

- Architect and philosopher, - BAVO and KU Leuven

- Ma Yansong:

- Architect, founder of MAD Architects

- Kristian Koreman:

- Architect, co-founder of ZUS

Kristian Koreman: Our task, as architects, is not just to design public places, but also to make space open to all through various forms of activism.

The pandemic has placed new emphasis on the collective and inclusive dimension of cities, making real-estate practices obsolete. This means we need to adopt new tools, which go far beyond expanding commercial activities on the streets.

Fabrizio Prati: In this respect, due to Covid-19, spaces we took for granted like public spaces and streets, in particular, were seen in a new light, a new appreaciation for a sometimes hyper-local piece of social infrastructure that could host necessary activities, such as physical exercise and play.

It was the streets that offered the greatest opportunities to multiply public life. In the first phase of the pandemic, there was a real urgency to adapt streets to guarantee the mobility of essential workers. Then when it gradually became clear that we would have to live with the virus for much longer, it became essential to recover outdoor spaces, often with interim tactical urbanism projects.

With the change in commuting patterns, the relationship with the city and its neighbourhoods also altered radically.

Today, the challenge is how to mak permanent these changes that were originally meant to be temporary.

Gideon Boie: If we thought in terms of a park or square before Covid-19 when talking about public space, this neglected urban feature has now quickly conquered the scene.

We’ve realized that public space begins right outside our front doors, and instead of a public responsibility it has become the object of our individual dedication.

For this reason, in Belgium as elsewhere, it has become a political issue. Changing the street, even with merely minor temporary projects, for some has meant interfering with the fluidity of traffic or the number of parking spaces.

This discussion about renegotiating and redistributing public space was a great resource amid the drama of the pandemic. The profession of the architect, at this crossroads, risks becoming obsolete if it is conceived only in relation to a client. The tactical urbanism during the pandemic has shown designers rethinking their role and becoming more activist.

KK: The awareness that we can use these urban spaces, even temporarily, for public and inclusive events has made the street the scene of new functions, where new types of users are active. In this respect, remote working has also been helpful. Those who previously only went to work at the office, now organise meetings outdoors or perform some tasks from the café in the same street.

What’s more, today the issues of climate and environmental health are seen as more closely connected, so much so that the very act of planting a tree in the city has a different significance from two years ago. Today we’re more aware of the fact that a green canopy projects a shadow that mitigates the overheating of the road surface, while improving the quality of the air.

All of this is part of a new and more complex articulation of urban space and part of the 15-minute city scheme

We can no longer think the use of streets in one-dimensional categories of transportation, because the boundaries between one action and another have become liquid.

GBI: The new users of the street as public space do not belong to fixed categories, and this is a new state of affairs after Covid-19. For instance, bicycle and pedestrian mobility has often been treated in the same way as cars, as if people walk or cycle just to get from one place to another. However, especially during the pandemic, the actions of walking and cycling have become synonymous with physical exercise, or exploring the city, or socialising.

The result is that we can no longer think the use of streets in one-dimensional categories of transportation, because the boundaries between one action and another have become liquid.

Ma Yansong: In recent months we’ve all explored the neighbourhoods and cities we live in with greater depth and curiosity. The quality of the public space that I personally appreciated the most was the spiritual and poetic one, which is independent of the dimensions or functions of a given environment. It lies in the potential for hosting unexpected situations.

The most precious things, as I see it, are the possibility and the freedom to invent the ways we occupy a place at different times. Often our cities are actually over-designed and, for this reason, constricting. So the question is: how can we incorporate the unexpected into our projects?

FP: Apart from the debates that have emerged in recent months, I’ve noticed that in New York, where I live, the change has led to a more spontaneous appropriation of the street. In the city I’ve often come across new unexpected activities such as impromptu concerts or convivial block parties.

So, following Ma’s thinking, certain distinctions, such as public- private or open-closed, might no longer be relevant. As citizens and users, we also see the boundaries between the various types of public space as more blurred.

We no longer automatically identify the street as being for movement and the square as a space where people can linger and relax. It’s as if these processes had put into action the vision of public space appropriation we’ve long been fantasizing of, but in a more pragmatic form.

Involving communities in the process could help ensure not only the the quality of the design, both urban and architectural, but foster the appropriation of these spaces. This also means the modus operandi can be changed or advance by phases and include the reversibility of the project.

KK: Returning to what Ma Yansong said about over-designed spaces, I feel it’s curious how much attraction there is to natural spaces, which by definition are less designed than urbanones. This has certainly nurtured ourdesire to find a new ways to coexist with other species, animals and plants, and manage our resources.

Involving communities in the process could help ensure not only the the quality of the design, both urban and architectural, but foster the appropriation of these spaces.

MY: I agree. Rethinking public space is now passing, and it will have to pass, through a renewed relationship with nature.

During the pandemic I visited the Classic Gardens of Suzhou, where the traditional Chinese residences have a large semi-public outdoor space, giving the impression that the artificial and architectural element extends into the natural one. I think that when our space is limited and densely built, nature offers opportunities for relaxing and freeing the imagination

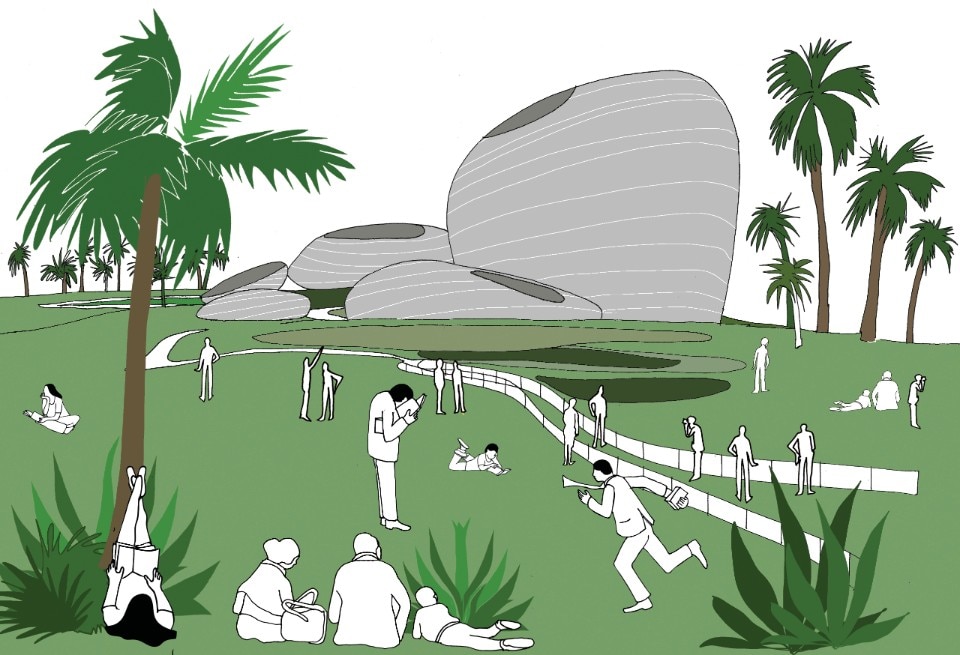

- Opening image :

- Illustration Anna Sutor