A historical winery (1608) – which has to do with a certain Countess Enzenberg – was to be extended in order to accommodate wine cellars, storerooms and a shop. Although Enzenberg wines have been produced for 400 years, Michael Goëss-Enzenberg, count, owner and vintner, still considers Manincor to represent a fresh start. And that fact can and should be made self-evident through the expansion of the cellar: he is not only a count and vintner but also the fourth “architect”. A project was developed to do justice to the parallels between the concept and the count’s attitude towards winemaking and the demands of the architects. Perhaps it has helped architecture to become “a bit more authentic”, particularly in this world of contemporary wine architecture where considerations of theatrical scenery and communications technology are often in the fore.

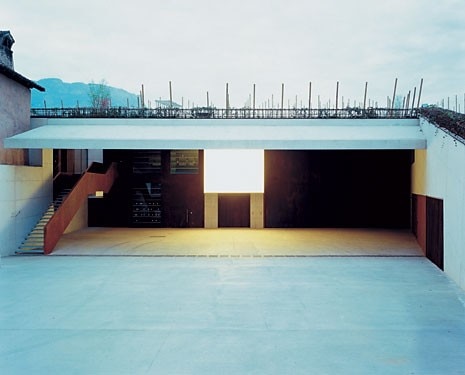

The new cellar is located to the east of the ancient building and it has taken on all the topographical characteristics of the location. The goal was to reinterpret the landscape rather than to change it. Only individual components come to the surface “extended” in relation to the pre-existing elements and functionally related to the surrounding wine landscape (wine selling, tasting, entry). The path to the upper vineyards and the views in and out define the spatial concept and structure of the building. This results in folds and inclined walls, not out of any outspoken pleasure in original design but rather in response to the topography. Building underground also makes it possible to exploit the geophysical potential. Covering the building and planting vines on top of it goes beyond landscape cosmetics. Deep in the ground are the real storage and fermentation rooms, which are connected with the old cellars. Circulating humidification and ventilation systems ensure optimal humidity and stable temperatures all year round. In principle, architecture needs to be “inhabitable”. This is another maxim of architecture, not only in the case of this building. Inhabitability by micro-organisms (a cellar must), a projected patina and the general use form part of the concept, together with a dialectical claim to complexity and materialisation, tectonics, space and light, phenomenology and semantic thinking. All this is intended to make every room what it is instead of becoming mere living-room architecture.

The high-quality concrete with an original formula will over time somehow take on the same greyish-beige colour as the site, while little “tricks and fakes” prevent it from being clearly definable as such. Rusty steel parts, not to impress contemporaries but because they represent the best form of conservation. Black parts, designed to fade out, as in the theatre or with the French existentialists. Good light, of both artificial and natural origin. Wood only where it makes sense, in shelves or barrels. A botanical concept of restoring nature. All these ingredients should suffice to season the meal and fulfil the architectural commitments. After all, it is the wines of Manincor not the building that should stand in the foreground.

Designing from a single gesture: Vaselli’s latest collection

The Hoop series translates a morphological gesture into a family of travertine bathroom furnishings, where the poetry of the material meets the rigor of form.