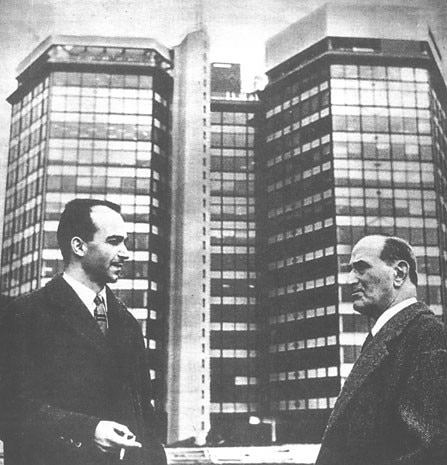

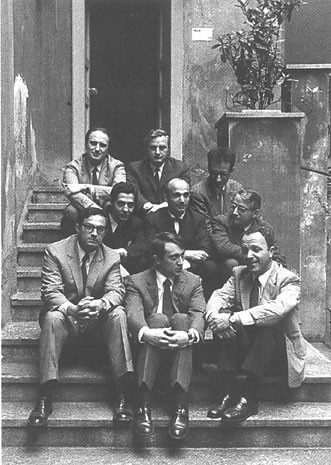

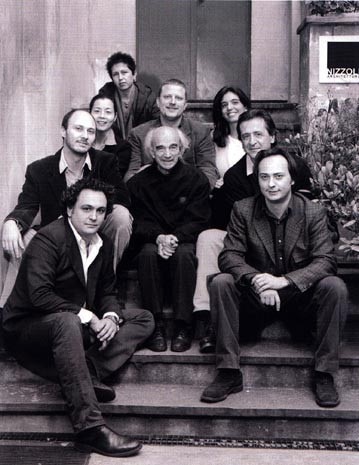

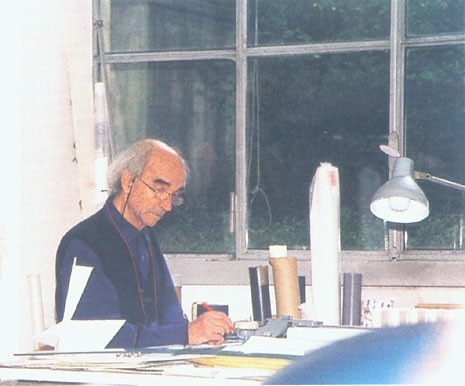

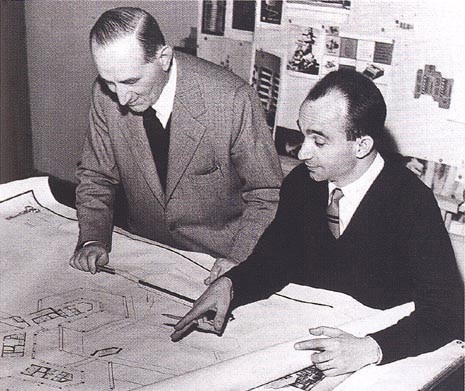

(…) I set foot in no. 3 Via Rossini for the first time at the end of February 1948. I was in fact again looking for work, and I had brought some tempera paintings (I painted a great deal then) (…) At that time Nizzoli handled three things: the design of Olivetti typewriters, the advertising posters and the fitting and furnishing of a sector of the Montecatini pavilion at the Fair in Milan (…) I also discovered the fascinating world of Olivetti, whose emblematic factory radiated its own image to the marvellous universe of the Hotel Dora (…) I met Leonardo Sinisgalli, Geno Pampaloni, Franco Modigliani, Franco Fortini, Augusto Morello and Giorgio Soavi and many others, including Libero Bigiaretti and Roberto Guiducci. It was 1950, the year of my degree, and I continued to go to Ivrea often. (…) In 1964, accompanying some architects visiting the ENI offices in San Donato, I had the good fortune to meet Alessandro Mendini. During the return trip to the city we spoke quite a lot and we experienced mutual interest and curiosity (…) Mendini introduced me to Paolo Scheggi, a visual operator, and Angelo Fronzoni, a graphic designer; with them we began to design a new professional studio that, leaving the traditional confines, moved into a more cultured and open circle (…) The new structure was given the name of “Nizzoli Associati” (…) In 1965 Paolo Viola came to Via Rossini (…) The beautiful trademark with the “N” of Nizzoli (two squares with a triangle in the middle) was designed by Fronzoni… After the exhibition in ’83 in Palazzo Dugnani and after Antonio’s departure (Susini), a new cycle began in the life of Studio Nizzoli: the characters, the works in progress changed, design practices changed with the introduction of the computer (…)Beginning of activity alone 1993-1994. Many of the “improbable architectures” executed in recent years coincide with this period (…) In truth, this exploration interested me a great deal and it seems to me that I was going through one of the most interesting, curious and intense periods of my long career. (…) The experience of the competition ended positively on the human level and on that of design understandings, and so the group with Mimmo, Michele, Gabriele and Nicola could be considered stable. I explained my ideas on architecture to them and in exchange they offered me the exuberance and inventive unscrupulousness that is typical of their age. Sometimes seeing how things stand as regards what is permissible to express with the means of architecture and what it is possible to express with light, projections, sound, feeling and so on (…)

G. Mario Oliveri

(…) Therefore (…) it is necessary for the decoration to be functional, from the expressive point of view, to the building; that is to say, for the decoration to pose as “spokesman” for a linguistic approach to architecture. So when is a decoration architectural? (…) Probably – in order for the decoration to be structured according to the building, that is, all one with it – the repertoire of its signs must certainly be that always used in construction (…) almost all the architecture of the past is connoted by the presence of decorative architectural motifs whose functions is directed towards contributing to the architectural “action”, which nobody dares criticise precisely because in a relief of bricks or stone. It is not clear by what prejudice the same signs become criticisable if created in two dimensions with painting. (…) Perhaps it is the time to re-examine what the past has produced, eliminating certain taboos and re-entrusting to decoration the role of spokesman of architecture (…)

G. Mario Oliveri

(…) One of the few italian architects who was able to follow its own “via maestra” (main way) – it is actually more correct to say its “via traversa” (side way) – definitely autonomous and often adveturous – (…) who, from the beginning, as partner of the important designer-architect Marcello Nizzoli – (during the 1950’s) was able to accept his fantastic inventiveness; therefore, during the tight collaboration period with Nizzoli but also during the following autonomous activity with associates, he succeeded in asserting himself and define what we could define his really personal “style” (…)

Gillo Dorfles

It would be pointless to try to reduce to the strictures of a linear and unitary interpretative scheme those magmas of visual elaborations and professional practices that mark the architecture of Studi Nizzoli – ranging from the construction realised … to the projects left on paper, from the objects that have entered our daily lives (…) to the sculptural fantasies, from the new disctrict-towns (…) to the urban utopias, from paintings as such (…) to applied decoration – with a scope covered by their field of cultural interests that is astounding to say the least.

Benedetto Gravagnuolo

(…) After the common experiences of the various studios rendering homage to the name of Marcello Nizzoli (…) a deeper aspect of Oliveri’s architectural vision emerges in this phase dedicated to personal research. This was an attention to the perceptive phenomena at the fascinating borderline where architecture, applied arts, cinema, literature and theatre interface. (…) Finally, there is also an understanding of architectural space that does not have its origin in principals and scientific convinctions, but in emotions, a spatial, expressionist vision (…) Many of the ‘improbable architectures’ date from 1992-94. These sprang from the desire to explore complex urban situations and give life to an architecture that was in some way different. (…) During his career, we find the word ‘expressionism’ increasingly replaced by the term ‘communication’.

Luigi Spinelli

(…) In the beginnning, then, was there colour or form? (…) The line (…) that Studio Nizzoli has brought forward in the last ten to fifteen years seems to me to develop a new discourse precisely in relation to the problem of history, of the historical forms that are cited, taken up, displayed, and of colour. No to the negation of the non-colour of the rationalist tradition, but no also to the resumption of US models of so called post-modern architecture that have other contexts, other relationships, for example with the universe of the “written” city and with advertising culture.

Arturo Carlo Quintavalle