Hospital

This unfinished communal hospital building in the North-West of Moscow is one of many abandoned medical institutes in the Moscow Region. Echoing the public services meltdown in a country in which averaged life expectancy has fallen from 63,8 to 57,6 years — a trend described in the UK medical journal The Lancet as “without parallel in the modern era” — this piece of decaying public infrastructure is temporarily being used as a training ground for anti-terrorist Special Forces. Laws were passed in 1994 to devolve the old centralised Soviet system, leaving it starved of cash by destitute regional authorities. “The crisis in Russia’s medical services is rapidly approaching a line, which if crossed, will lead to the collapse of the entire healthcare system,” says a recent draft Health in Transition Report for the World Health Organisation. Amid the turmoil of recent Russian history and the war in Chechnya, the fear is now that the Russian healthcare system could implode altogether, at a time when the country's people need medical care more than ever.

Arkhangelsk

Home to both Russia’s Northern Fleet and the largest concentration of Soviet prison camps known as Gulags (an acronym for the government agency that supervised the vast network of forced-labour camps), Arkhangelsk was a destination for WW2 convoys that delivered equipment from the USA and Great Britain to the Soviet Union. Its blend of geographical isolation and prison camp history induced Solzhenitsyn to write the Gulag Archipelago series after being released in 1956. This history and memoir of life in the Soviet Union’s prison system uses the word archipelago as a metaphor for the camps, which were scattered through the sea of civil society like a chain of islands. Today, a repair shipyard is located near Arkhangelsk, where the State company Severny Raid upgrades the Russian submarines awaiting dismantling. Each year approximately 11,000 cubic meters of liquid radioactive waste and 3,000 to 3,500 cubic meters of solid radioactive waste are generated by the Northern Fleet. Rusting hulls of nuclear submarines, which are laid up at docks, leak radionuclides into the water. Nowhere else on earth is there such a concentration of civilian and naval nuclear reactors. According to the Yablokov report, an official Russian document, there were a total of 270 nuclear reactors in Murmansk and Arkhangelsk counties in 1990. Nuclear activity includes power plants, nuclear submarines, huge piles of nuclear waste and the effects of nuclear tests conducted by the former Soviet Union.

Central Heating

Moscow is provided with space heating from 25 combined heat and power (CHP) plants. Annual maintenance of Moscow’s 2,400 kilometres of heating lines eliminate an average of 4,700 defects on the pipelines, while the city’s heating system annually consumes as much natural gas as all of France. The ageing centralised heating system that pumps heat around town by means of underground pipelines spills out boiling water into everyone’s home from a central reservoir resulting in limitless 24 hour hot water and over-powering heat from the radiators. Moscow’s environment has long suffered from industrial pollution; however, about 60 percent of the city’s air pollution now comes from automobiles. Radioactive waste sites, unauthorised trash dumps, and deforestation of the Green Belt that surrounds the city are being addressed by federal and local agencies. Moscow Heating Network, who is in charge of the main pipes that ship steamy-hot water from power plants to neighbourhood heat-exchange points, sees the city's saviour in a new pipe that is resistant to rust. A special water- and heat-proof coating that is several centimetres thick and filled with rust-fighting polyurethane foam protects the pipes.

Centre for Curative Pedagogics

During Perestroika, a group of parents of children with developmental disorders teamed up with psychology professors from Moscow State University to initiate a non-profit organisation that helps those children to adapt to the real world. Founded by Anna Bitova and Roman Dimenshtein, the Center for Curative Pedagogics is an independent, non-governmental centre where disabled children receive various forms of therapy. It gives families who want to raise their disabled children a day care alternative to governmental institutionalisation. The Center operates a computer communications network between NGO’s, which work in children's disabilities rehabilitation throughout Russia. The project received a license to begin operating in 1991, the same month that hard-liners staged a failed coup against Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin banned the Communist Party. By now, the Center has an enormous amount of documentary evidence of disabled children's parents officially denied the services of developing the disabled child secured by law. Human Rights Watch called the conditions “inhuman”. More than 200,000 children are classified as being "without parental care" and placed in orphanages, though as many as 95% of them still have a living parent. Roman Dimenshtein, who co-directs the Center, traces the problem back to Socialism when the State's solution was to warehouse these people from birth and keep them out of public view. And that approach largely continues today. The Russian government has publicly announced steps to improve conditions in its orphanages. But Human Rights watch concluded the proclamations have yielded few results.

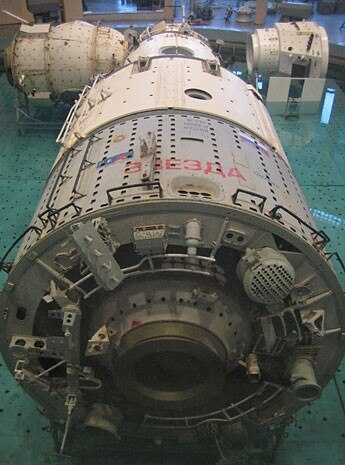

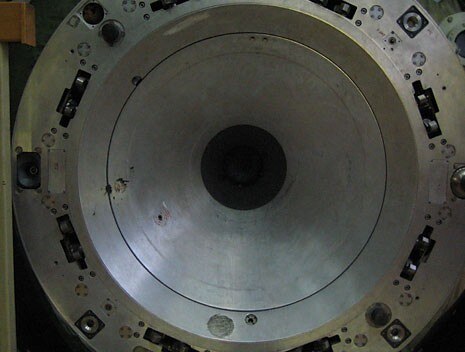

Star City

1 of 2,200 candidates selected in 1959 Yuri Gagarin might have lived among the 6500 people granted life-long housing and education in Russian name had he not crashed into a forest in 1968. Star City, a bastion of the Soviet era, in both symbolic and real terms, lies 50km south-east check of Moscow hidden by birch trees and a recently rescinded policy of secrecy that ensured its absence form Soviet maps.

KGB

The All-Russian Extraordinary Committee to Combat Counter-Revolution and Sabotage, State Political Directorate within the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, All-Union State Political Board, Main Directorate for State Security, People’s Commissariat for State Security, Ministry for State Security, Committee of Information, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Committee for State Security, following the removal of several directorates, the KGB is now known as FSB – Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation and has been subject to more name changes in its century history than any other intelligence organisation but has been unable to shake off its reputation for brutality and ruthlessness in dealing with internal unrest or political “subversion”. In 2001 Tony Blair met Vladimir Putin to discuss greater collaboration between the British Security and Secret Services and the FSB. In 2006 their relationship was made newsworthy not through anti-terrorist success but with the exposure of a SIS radio transmitter rock, in a Moscow park. Presentation chamber of the FSB in Moscow. The bound volumes beside the lectern contain names and photographs of former KGB officers including its Director from July 1998 to August 9th 1999, Vladimir Putin, his chief secretary and deputy chief of Kremlin administration Igor Sechin, Yuriy Zaostrovtsev, FSB Deputy Director in charge of Economic Counter-Intelligence who led the operation against former oligarch Vladimir Guzinsky, iktor Ivanov, deputy chief of the Kremlin administration in charge of personnel (both in the Kremlin and the Russian government).