The Cult of the Vineyard

Dietmar Steiner

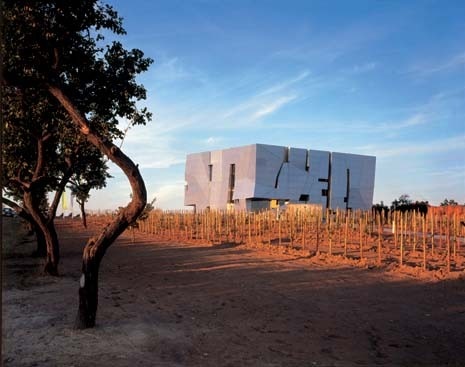

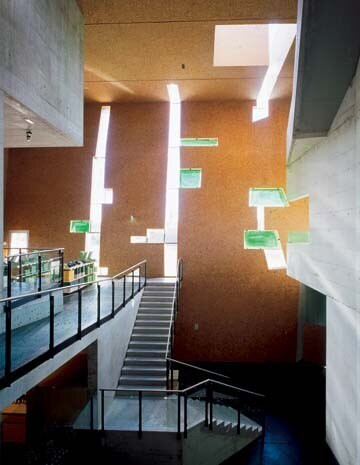

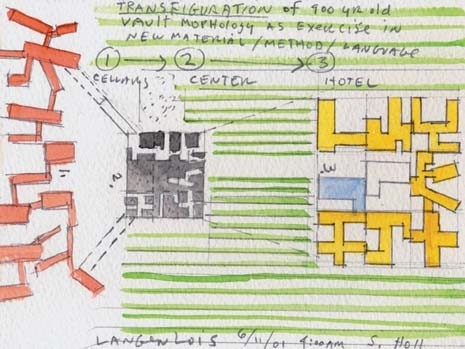

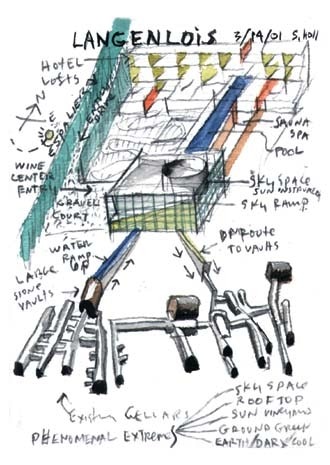

After all of the museums and fashion boutiques, after Guggenheim and Prada, there has for some time now been an additional, unexpected field for architecture, one that has to do with sophisticated lifestyles. All of the world’s star architects are surely building or planning wine estates; if not, they have at least engaged architecturally with the theme of wine. And there is hardly an architect of stature who is not a more or less self-styled wine connoisseur. It is no coincidence, then, that these two essentials of life – wine and architecture – have discovered each other in recent years. Their cultures are structurally very similar. Your everyday, average plonk can be compared with just putting up a building. Wine connoisseurship and architecture grow on this foundation only when we leave behind the troughs of the everyday and ascend to peaks of sophistication in production and appreciation. That said, we might add that most of the world’s building ‘yield’ probably does not reach even the workaday level of vin ordinaire, standing in comparison only to canned lager and industrially produced soft drinks. Sophisticated architecture and wine connoisseurship, by contrast, are both characterized by the mutual dependence of producers, critics and consumers. A product’s grade of quality is defined by the critics, professional connoisseurs who have no objective criteria, but rather base their judgement on knowledge and comparisons. Architectural critics, who are closely enmeshed in the production of architecture, determine the value of architects just as wine critics do with the products of wine growers. Both are faced with overflowing production; they compare, they taste, they assess the achievements of big names and at the same time search for new, hitherto unknown producers. Thus wine writers and architectural critics share a comparable attitude. They are anarchically sceptical toward the major products that dominate the market and are continually on the lookout for innovative new regions and ideas that can generate an original or regional culture. And for consumers, this creates a guide for quality assessment, a narrow path of refinement in the jungle of consumerism. Steven Holl’s wine pavilion project has developed precisely on this level of dialogue between oenophiles and architecture. The starting point is Austria’s new wine culture. For various reasons – the 1985 wine scandal, the consequent total collapse of the market for cheap wine, a change of generation among wine growers – Austria has seen the development in recent years of a small but exquisite new wine culture whose demands and achievements have achieved international recognition. This is the foundation on which a number of committed wine growers and investors in Langenlois, the largest wine-growing district in Austria, have built the idea of undertaking a special project known as the Loisium. Their beautiful old houses, which date back in some cases to the gothic era, are built over a huge labyrinth of ancient wine cellars that are no longer needed today. The idea was to develop a didactic concept, involving all the senses, to make this ‘cellar world’ accessible to the public. This is the basis for a tourist programme developed by Steiner-Sarnen, a Swiss firm specializing in museum concepts. In the midst of the beautiful vineyard landscape of Langenlois, they envisioned a ‘visitor’s centre’ to stand as a clearly visible architectural symbol of the staged subterranean cellar world. It is perfectly typical of the cultural level of today’s wine community that the investors selected none other than Steven Holl as their preferred architect. At first they did not believe that Holl would be prepared to build a small pavilion for the hitherto unknown Langenlois. But Holl, once he visited the site, was fascinated by the location and by the elemental power of the ancient cellars and was full of enthusiasm for the sophisticated wine culture. Is it a coincidence that Langenlois’ Grüne Veltliner grape variety, similar to chardonnay but more sensitive and sophisticated, has now become a cult wine in Manhattan? Holl has translated the structure of the subterranean cellar world into an architectural concept for the visitor’s centre. The pavilion is the expression of a ‘middle world’. Holl took the idea of an abstract block 25 metres square and 13 metres high and tilted it by five degrees toward the entrance to the underground world. He developed an absolutely minimal exposed concrete box with walls that were deliberately thin (25-centimetre) and large enough in span to pose enormous challenges to the structural engineers. Holl’s sympathetic local contact architects, Franz Sam and Irene Ott-Reinisch, were able to execute this concept with the help of no less committed local builders. The box, clad on the outside with a thin aluminium skin and on the inside with thin cork panels, is structured with openings that can be understood as a metaphor for the ground plan of the subterranean cellar. Holl’s pavilion is the entrance to a world of experience. From here visitors travel through the vineyards alongside a pool and take an elevator down into the staged world represented by the cellar itself. They lose their bearings in this 800-metre labyrinth and are surprised to find themselves back beneath the pool, which can be seen through glazed openings, and at the pavilion, which presents itself as a huge three-storey space. This foyer will provide a venue for events and will eventually house a shop, a ‘vinothèque’ and a cafeteria. Holl’s Loisium is a uniquely valid monument to the union of architecture and wine connoisseurship, heralding modernity, sensuousness and taste. But this is not the end of the Loisium project. Before the year’s close, construction will begin on a small, high-class hotel that, following the visitor’s centre, will round off this concept of modern leisure and lifestyle. Or, as Holl puts it, in pragmatic American fashion, the cellar world will be ‘underground’, the pavilion ‘in the ground’ and the hotel ‘aboveground’.

Steven Holl and Nihilism

Pierluigi Nicolin

In the early 19th century, the term ‘nihilism’ was generally used only to accuse Kant’s philosophy of dissipating the world into appearances and depriving it of its substance. The word was adopted to define the concept by which only the being with access to sensitive perception – i.e., tested in person – is real, nothing else. This refutes everything founded on tradition, on authority and on any validity determined otherwise. The concept of ‘nothing’ can also unfold in other directions. It can adopt Asian overtones, leading to the contemplative sense of the sublime via the virtue of absence. I addressed this prospect some time ago during Steven Holl’s presentation of his Japanese houses in Fukuoka, when he was suggesting a link among his work, Zen and the vision of the universe in a grain of sand. At the time, I expressed my admiration for his architectural results as well as some perplexity concerning a certain distortion of the vision or mysticism, decrying the expectation of gratification from some assertion in the Western logos. At the time, disappointed by the large-scale experience, Holl was ‘only’ going to present his Japanese project via beautiful pictures of details and minimal events such as the water basin struck by the first drops of approaching rainfall, the shape of a step contemplated ecstatically or a light effect caught at a particular moment. Things have progressed since then; today in architecture, the word ‘nihilism’ basically means ‘more’. I now better understand what the young American architect, who seemed to embody the characteristics of the two coasts (translated into European terms, the characteristics correspond roughly to differences between north and south), was getting at. His phenomenological architecture and above all his descriptions swayed between New York’s ingenious taste for theoretical reflection and the refined hedonistic development of past avant-garde themes, a development that can be learned fairly well from Italian architects acquainted with the experience of Carlo Scarpa. Besides, Holl did not seem to have the cabalistic and all-cerebral attitude of an Eisenman tackling the dissolution of the supreme values of Architecture. He seemed more interested in dwelling on sensations. Eisenman believed that acknowledgement of architecture’s lack of sense as a dead language developed a desire for creative destruction that is still will – therefore not total annihilation, which would be the renunciation of will – and consequently still something that has to do with the logos. He seeks a passage toward a hereafter without believing in the previous categories of reason, believed to refer to a purely fictitious world. Nor does Holl think that ‘more’ springs from a mere obsession with blind destruction and vainglorious innovation; it stems from the necessity to seek a way through a situation in which architecture appears to lack value but, at the same time, requires a new one. We can use the word ‘architecture’ for the form taken on by this experience, caused by the abandonment of the now-surpassed architectural category prompted by the awareness that one world has ended and the perception that something new is imminent. In Holl’s work, what undergoes a sort of transmutation belongs to that sensitive world to which he applies his experience. Having gone beyond the Zen phase of the search for the absolute via sensation, he can now make new conjectures and anticipate the forms of a genetically modified environment with the conviction that – though the world’s theatrical stages, still conventionally portrayed by architecture, may stay the same for a while – a different play is already being acted out. In short, the previous dematerialization may seem an attempt to free the sensitive world from the values that have applied thus far, but we are now faced with the search for liberation via a resolute trans-valuation of all these values. After being subjected to the most radical deconstructive criticism and the questioning of traditional values based on horizontal and vertical order, hierarchy, duration and representation (in short, the characteristics peculiar to the imaginary projection of its ‘form’), architecture is now seeking an exchange or assimilation with the morphological processes of nature. The challenge involves crossing, albeit symbolically, a strong and ancient boundary – that between nature and artifice, ‘between what is there because it comes from within and what is there because it has been constructed’. Although stripped of its founding categories, architecture cannot abandon its physical substance. The architectural work remains a manifestation of the desire for power over a nature that others would like to see untouched. While architecture, if it is to exist, needs a body, we would like this body to live or at least be considered as something developing in a strengthened nature. Attempts to break through traditional boundaries between nature and artifice now occur on territory no longer controlled by the system that previously governed the discipline and can only produce a weave of perspectives, positions and values in a multifarious advancement. As part of this race to trans-valuation, Holl’s architecture has also recently abandoned previous patterns of research into modern forms, venturing into direct exchange with the forms belonging to the landscape and nature. The world of nature is now seen as a body, and the landscape as a skin on which to intervene in various ways. In this sense, architecture undertakes to redesign the landscape; in one case it serves to re-map or redesign the landscape to render hidden or unclear figures visible; in another it adapts an existing landscape to a new sensitivity; and in yet another it mixes or overturns the traditional opposition of nature and artifice, investing the building with an organic, sensitive imprint, causing the landscape to act as a fixed backdrop, serving as a reference to the changing dynamics of the architectural construction. In the case of the MIT dormitories, where the building is the landscape of the urban skyline, we witness an attempt to place the two themes in a single object via an ingenious number of scale changes and superimposed forms. In this search for an exchange between architecture and environment, Holl’s tectonic masks may be compared with certain research by Juan Navarro Baldeweg, well explained by Sandro Marpillero in his analysis of the Chapel of Saint Ignatius at Seattle University and the extension and library for the Woolworth Centre of Music at Princeton University. By using a Duchamp-like title for the Turbulence House, under construction in New Mexico, Holl is saying he wants to create an installation that works with the concepts of atmospheric turbulence and changing light. In this case, the reaction to the amazing atmospheric phenomena of the region is the theme of the building, and the shapeless metal shield is intended as a conformation directly generated, without the mediation of local vernacular architecture, by the unusual environment of the New Mexico desert. In the Loisium visitor centre, a hospitality structure in a vineyard near Vienna, the situation was produced by the existence of a magnificent system of underground vaults in the adjacent town of Langenlois and by the surrounding fields, containing rows of vines and a hotel. The centre is set in the vineyard between town and hotel and it comprises a wine and souvenir shop, meeting room, offices and spaces for events; it also serves as the entrance to the vaulted cellars, reached via an underground route reiterated on the surface by a sheet of water. The project stems from a creative interpretation of the context: the idea of giving the new stereo-metric volume ‘inscriptions’ based on the geometry of the old vaults develops a theme similar to that addressed by Juan Navarro when he constructed his replica of Spain’s Altamira caves, which are no longer open to the public at large. This very comparison helps to pinpoint Holl’s position in the present race toward the trans-valuation of architectural principles. Navarro’s case comprises all the doubts raised by having to ‘realistically’ duplicate a place that is now inaccessible, and his efforts went into transforming this replica into a ‘concept’. To introduce the darkness of the faithfully reproduced caves, he invests the interior of the shell encasing the replica of the famous monument with turbulence, as if a flux or an atmospheric fluid were penetrating from an outside infinity. The intention to create a copy in proximity to the original, trying to avoid its being confused with the real thing, brought the theme of the ‘mirror’ into the project, indicating the connection between the real and the virtual. At Langenlois, Holl adopted a more voluntaristic and, in a certain sense, more cryptic route. The Langenlois caves are open to visitors and remain the local attraction, so the architect addressed the theme by forcing himself ‘not’ to construct new architecture in the middle of the vineyard. Moreover, he had to avoid the new volume’s acting as a substitute structure, making a visit to the caves superfluous. All of this contributed toward finding a way to keep the new intervention undecipherable, so to speak, within the terms of an obvious architectural code. Secured to the countryside and to the vineyard, with a mission to represent the colonial appearance of the architecture with its geometrical order, the new building seeks to represent a state of nature entrusting itself to a telluric image that preceded the introduction of this order. As a result, the reference to the old vaults and to the cave as the first principle of architecture cannot be revealed in the current architectural representation.

The New Brevo House by Pedrali

Brevo has given its Parisian headquarters, La Maison Brevo, a major makeover, prioritizing innovation and employee well-being for its 400 staff members. The furnishings, curated by Pedrali, transform the 3,000 sq m of interior and exterior space into dynamic, stimulating environments that foster collaboration and diverse work styles.