Spain’s vote-hungry local politicians have been unanimous in their enthusiasm for using urban regeneration as a means of self-promotion, and they have opportunistically gone about securing the maximum subsidies for their cities from Madrid and Brussels. The recipe is the same from Barcelona and Bilbao to Valencia and Santiago de Compostela. But it is the size of the city that ultimately determines the scale of the intervention, and the qualities of specific commissions are shaped by the individual judgements of local communities.

Having previously worked successfully on the urban edge, the late Enric Miralles and his partner Benedetta Tagliabue were commissioned in 1994 for one such regeneration project, the upgrade of a peripheral slice of Mollet del Vallés, a not very appetizing dormitory town in the industrial belt of Barcelona, ten kilometres northeast of the Catalan capital. The result, which took seven years to realize, is the Park of Colours.

‘I want to make a park that people can eat’, Miralles is said to have exclaimed with his typical passionate enthusiasm during the design process. Whether this comment is anecdotal or not, some of the first-draft sketches of the project show a figurative map of different everyday situations, playfully represented as coloured patches that resemble large fruits. Tagliabue, co-author of the project, recalls the influence of a David Hockney drawing from the China series, the artist’s narrative of an imaginary trip.

The park in Mollet, which initially included a building for a community centre and a children’s play centre, occupies approximately 10,000 square metres, once an expanse of anonymous land between the residential areas of Santa Rosa and Plana Lledó. The area’s lack of any specific characteristics demanded a redefinition of the site; a new set of urban codes helped transform it from a marginal place into a shared public realm capable of meeting the high expectations of local residents. The initial condition of the project, which existed more in the ambition of the community than in the actuality of the site, was treated as a notion of social landscape – a recombination of new topography to create a meeting place and stage for public activities.

Although the Park of Colours offers various approaches, depending on the point of arrival, the overall experience is of entering a dreamlike space. Whether entering from the west, gradually descending into the park through its layered surfaces, or from the east, discovering the park little by little through the trees, your steps are guided by the frozen landscape. This artificial topography lifts the area once destined for the community centre – in the northwest corner of the site – above ground, setting up a meandering path around the park and defining spaces for activities or rest along the way. Halfway around the border, the vista widens to a ‘balcony’ before turning into a wide access ramp to the park. From this point, with a garden unfolding beneath you, the familiar childish invitation – ‘shall we play?’ – irresistibly suggests itself.

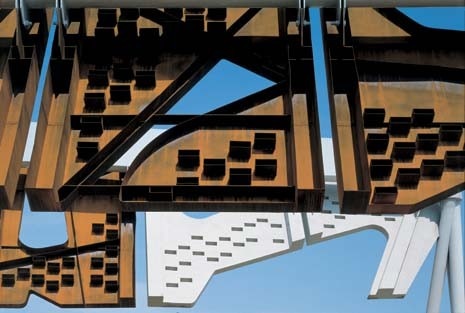

Immediately below, a flight of steps climbs the air above the multicoloured floor of the outdoor theatre. Screens on pillars designed to resemble graffiti strokes, as if the graffiti was the only part left of an eroded wall, circle around the theatre before marching off into the park. The light sifting delicately through the screens, creating varying zones of sun and shade, redefines the zones of activity according to the hour of the day or the time of year.

With the cemetery at Igualada, Miralles had been experimenting with what he described as ‘the way that different conditions of time can be expressed by form’. Just as in the cemetery, the radical geometry of the Park of Colours gives you a sensation of moving through timeless space. This interrelation between different Miralles projects, a literal translation of information from one plan to another, puts the design into a wider context. The park is an authentic display of different time shapes, of varied notions of the passage of time, most ingeniously resolved in the idea of a place ‘where it rains every morning’, evoked by the traces of water left by the discontinuous spurts of the fountains. Their rounded shells, covered with blue ceramic, glitter through the trees like small pools of petrified water.

Poetic allusions to the notion of time are refreshingly contrasted with the deliberate clumsiness of the urban furniture. In the same way that the memory of a beautiful dream or unforgettable voyage gets its beauty from the passage of events, the park’s scenery is not appealing because of the physical appearance of individual objects. The design provokes you to engage with the sense of scale in a playful game of details, alternately making you feel too small, dangling your feet above the ground while seated on one of the benches, or too big, coming up too close to one of the sturdy, gnome-like lampposts. Throughout the park, the vegetation is treated as a structural element. Grouped by species, the trees – like small artificial forests – contribute to the functional divisions of the park: mulberries align the children’s playground up on the balcony, willows surround the fountains down below and eucalyptuses pair up along the perimeter.

As in the work of Antoni Gaudí or José Maria Jujol, the semantic contamination between the natural (vegetation) and the artificial (furniture) combines to create a fantasyland, which at times gets a bit tiresome. It’s a dream, but whose dream? In the case of the Park of Colours, Miralles insisted on the important role that his continuous dialogue with the neighbourhood had on the evolution of the project. The festive character of the place is derived from its social topography. It’s a way of overcoming the deficiencies in the original site to meet the desires of a place of encounter.

I visited the park at its opening, a warm, dark night in July when it was full of people enjoying Fura dels Baus’s spectacular inaugural performance. There was a medieval air to the place as a giant mechanical woman made love to the park through flames of fire, while the actors – suspended in the air from cranes – bounced around her like amorous fireflies against a background of flickering light from huge projections. The main ingredients of the spectacle – the contradicting messages, the juxtaposition of time, the play with scale – reflected the spirit of the park’s design. In the dark, spectators, unaccustomed to the new landscape and pushed around by the crowds, were continually tripping over one another, but not even minor accidents seemed to diminish the excitement of the occasion. When I returned on a bleak Sunday morning in the beginning of December, a year and a half later, I was curious to see how the park was working ‘on its own’.

One hectare is not a big area for a park, but although there was quite a lot going on – a group of pensioners playing pétanque, children tumbling around at the playground, two girls having an improvised breakfast, a couple of skaters at the theatre, a family walking their dog – it didn’t feel crowded. The park has ‘enough distance to mark out your own territory’, as the Smithsons would say, and yet you can always get a view of what ‘the other’ is doing. Through its combination of differently textured materials (coloured concrete, brick, ceramic, steel and wood) and the ever-changing lights and shadows, the park appears iridescent and unpredictable, right down to its most remote corners. You can discover it step-by-step as a toothsome metaphor of the multiple aspects of the city, or you can experience the overall view as a voyage leading from the top tiers of the outdoor theatre.

Ultimately, the Park of Colours offers no coherent reading. Instead it comprises an infinite number of possible accidents, each with its own meaning, all equally important. It is a social landscape in which the absence of hierarchy allows new situations to occur as relationships are established, reflecting its mission as a profoundly urban intervention.

Stone: Origins and Future in Architecture

On June 12 and 13, 2025, IUAV University of Venice will host "Stone is…," an international forum entirely dedicated to natural stone. Organized by PNA, this event aims to thoroughly explore the material's enduring value and sustainability, featuring insights from internationally renowned speakers.