The habit to explore places that tell stories has its roots deeply sunken in the history of Domus, be it about visiting “someone’s” place , presenting artists’ houses, or generally introducing architectures that owe much of their space and form to the personal and artistic journey of those who live and lived there. In 2002 it was the turn of this house built, but above all conceived, by sculptor and architect Walter Pichler, in a place linking tightly to his origins: Eggental, a valley in the South Tyrolean Dolomites.

The textual portrait of the artist penned by Paolo Piva, built through the spaces that Pichler conceived, is also a first twofold occasion to explore the Domus archive: after appearing in July 2002 on Domus issue 850, the article was immediately followed by its synthetic publication on then rather young — not to say almost newborn — medium: the online magazine Domusweb, where Pichler's house was published in August of that same year.

Artist’s House

Paolo Piva on the architecture of Walter Pichler.

Photography by Elfi Tripamer

The Austrian artist Walter Pichler has dedicated a long series of drawings to exploring and celebrating the mountain valley in which he has lived and worked for almost 30 years. They convey the unmistakable intensity and emotional charge hidden in those settings. In them you find the characteristic rock faces and the waterfall that, if you listen hard enough, you can almost hear rippling, the tiny patches of grey sky that sometimes open into lighter colours. More than narrating, he is remembering.

Memory is also the key to Pichler’s new architecture. The memory of a child’s farewell to a dark valley full of charm; the memory of a little house, steeped in mystery; the memory of a harsh and intense place that will always keep the secrets of a childhood that will be all too soon interrupted. The silence of the mountains contains all of the elements that recur in the work of this sculptor who, far removed from the transient sensationalism of so much contemporary art, has always looked, above all, for a sense of rootedness and place. Pichler’s architecture distances itself from the everyday conventions of design to create places that are dedicated to accommodating his sculptures, works that are as fragile as they are careful of all that surrounds them.

St. Martin, where the artist has worked since 1972, is a small town, a village inhabited not just by people but also by Pichler’s sculpture. Sheltered by fragile architectural casing, they live protected from the elements. This architecture is given the role of containing what is most important to an artist – his work.

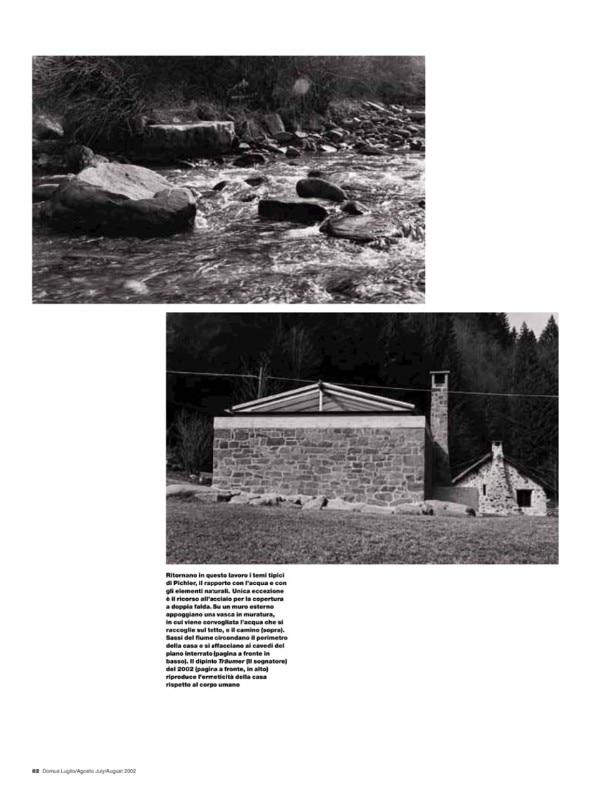

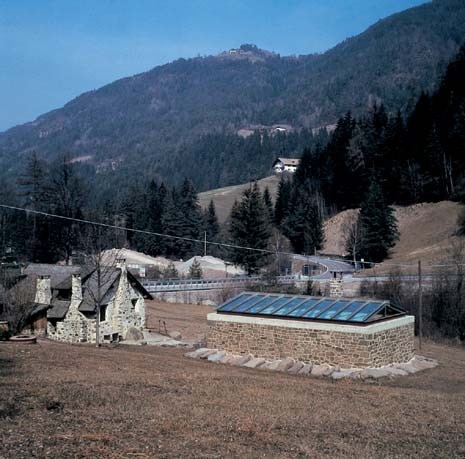

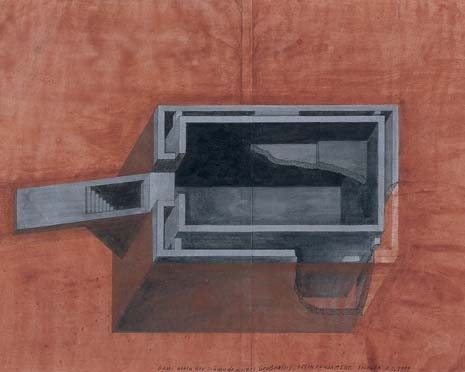

With this new project the artist returns to the scene of his childhood. Pichler revisits the typical little black houses of the Latemar and Rosengarten mountains, but he encloses the form with a minimal perimeter and looks up at the single patch of sky visible from the valley. A large window separates the space from the outside and from the great rocks that have rolled into the river to become guardians of a sometimes over-loud silence.

The new work is carefully positioned at a distance from an old workshop and the space used to define a small courtyard that is the heart of the new house Pichler has built for his cousin. A closed facade, broken only by an iron door and reached via a path lined with porphyry monoliths, flanks the existing workshop without dominating it, making it an integral part of the new design. The comparative architectural scale of the two buildings becomes an almost philosophical ‘reflection’ on different eras and generations. Distant in time and with diverging functions, the two realities that stand in the same place share a similar attitude, the first bound to story and experience, the second shaped by intense memory, gratitude and a sense of belonging.

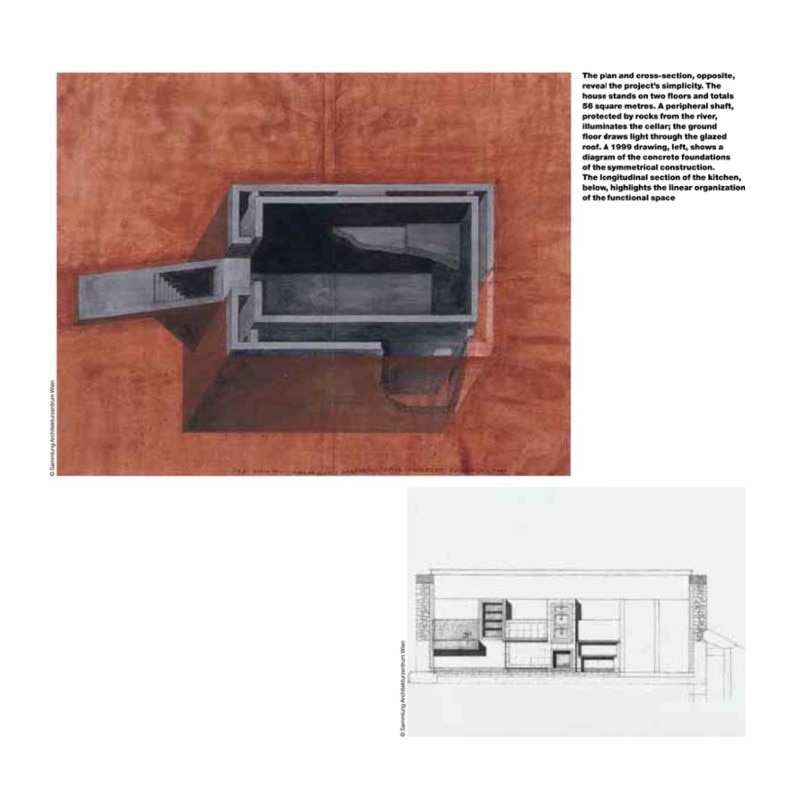

The stone-clad construction is developed on two levels. The basement floor, ventilated by a peripheral shaft covered with large river rocks, is used as a cellar, and domestic life inside revolves around a large, central wooden table. Light penetrates the shafts, filtering through the cracks between stones. When it rains, water comes flooding in to be channelled into the nearby stream.

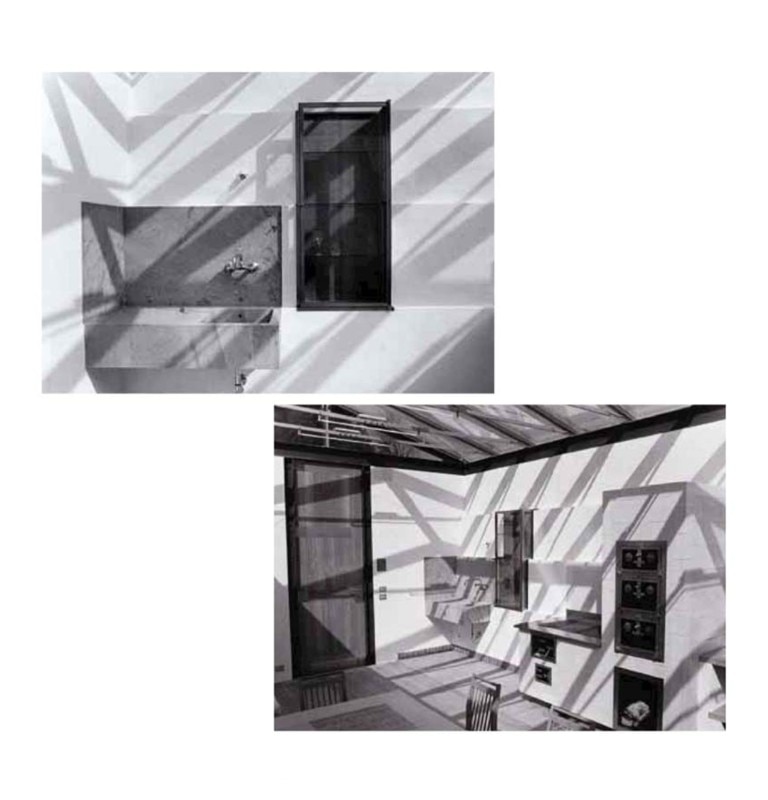

The living area proper is situated on the ground floor and draws its light from the large upper window. Everything that seems closed from the outside opens into a furnished internal space where all is positioned according to the elementary principle of function. It is an efficient and minimal – but not minimalist – space.

The stove resembles the ceramic stoves that are characteristic of the region, but it is covered with plaster, almost as if to refute all elements of decoration and nostalgia. The sink, hewn from a block of stone, is set into the wall, and the steel and glass cabinet containing glasses conjures up the fragility of its contents. The wooden table may be flanked by a mobile piece of furniture that doubles as an extension and a worktable near the cooking area. The chair is a designed object, carefully reproportioned and produced in small numbers using the wood from fruit trees. Every component reveals the complex simplicity of one who knows that life is lived in routine things and that every humble gesture embodies the greatness of a major work. The large roof is the only element that dates the project.

The skilful use of steel tympanums and the composition of the large double window ensure that the structure can also be used at times of particularly harsh weather. Just as rainwater penetrates the shafts and is channelled outside, so too the snow that falls on the glass structures fills the home beneath with white light, departing by way of an external basin placed around the chimney of the central stove that organizes the interior space. The heat of the stove melts the snow, which collects in the basin before being returned to the river. All of this is simple, but the simplicity contains the complexity of Pichler’s work. Every object, every sculpture gathers the fragments of a continual, unstoppable flow. Neither satisfaction nor nostalgia but certainty – the certainty that the greatness of the work lies in the ordinary gesture. This is the key to the interpretation of this small but grand architecture, not a skyscraper, not a large industrial complex, but a ‘little house’ that can only make us think.

- Design:

- Walter Pichler, Vienna

- Structural engineering:

- Christian Rigliaco

- Masonry:

- Hans Weissenegger

- Interior stonemasonry:

- Josef Dalle Nogare

- Client:

- Walter Pichler, Bolzano