For almost 15 years I have been systematically working with young designers and their creative projects and careers. Since as far back as 2007, while working on the opening of the Triennale Design Museum (the first “mutant” museum in the world, dedicated to Italian design) and the consecration of the history of Italian design, I have felt the need to map and highlight the work and the talent of new generations. With the help of Andrea Branzi, an exceptional curator, we organised a detailed and systematic exploration of a sector that is not easy to define. As well as an exhibition, what emerged was a kind of manifesto. At the time we maintained that design in the 2000s was positioned in - and operated from - a paradigm that was decisively different from that of the period of the “Masters”. The main objective was no longer to create complete, functional and defined products, but rather to produce processes that represented one’s own ability to imagine, create and innovate. 13 years have gone by since then, and things have, in part, changed.

Undoubtedly COVID-19 has played a significant role. However there are other factors. Even before the epic fracture that the pandemic set in motion also in the world of design, for some time there had been strong signs of change and a growing need to redefine the roles of design in a world that was - and still is - undergoing dizzyingly rapid change.

View gallery

View gallery

Tip Studio

Lovers of craftsmanship and experimenting with materials, in their recent design, Secondo Fuoco, the young designers Imma Matera and Tommaso Lucarini have chosen to focus on the useless, on left-overs, on discards. In collaboration with the Fonderia Artistica Versiliese, these designers collect discards from the casting process; they then cata- logue them based on types, trim them into small fragments and, finally, pair and immobilise them with wax. They are then subject to further casting (a “second firing”) that creates new and unique objects: small material sculptures, each containing clashing elements (cold/heat, smooth/rough, shiny/ matt). In addition to cast bronze, elements in glass, marble and steel are also employed and paired, to accentuate the intentional material hybridisation that is at the heart of the entire design, poised be- tween art, artisanry and design.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diary 05/20

Giuseppe Arezzi

A multipurpose object to furnish a minimal living space: those tiny houses measuring a little over 10 m2 (the so-called chambres de bonne, or servants’ chambers), built in the attics of early 19th-century Parisian homes, today oftentimes occupied by students. Giuseppe Arezzi – Sicilian by birth, Milanese by choice – designed Binomio (edited by It’s Great Design by Margherita Ratti in Paris) precisely for this space, as the prototype of hybrid furnishing, with three shelves at three heights: it can turn into a desk or a dresser, but it can also be used for hanging clothes, or as a bench, a small table and even a kneeling-stool. Both rigorous and visionary, with a design approach deriving from careful social-anthropological analysis, Arez- zi belongs to that generation of designers who re-ex- plore ancient craftsmanship traditions in order to offer innovative solutions to the needs of contem- poraneity.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diary 04/20

Antonio Facco

Milanese, trained at the IED in Milan, among his collaborations we find Cappellini. Antonio Facco theorizes about the boundaries between art and design and explores the lesson of the design Masters, starting with Vico Magistretti, to decline it in today's landscape. His works range from product to interior.

Ilaria Bianchi

Her starting point is experimenting with materials. Ilaria Bianchi chooses antithetical ones, manipulating them so as to create multisensory engagement in the user. With Bicaudata, Bi- anchi makes a sort of small, slender and delicate vase, beginning with an industrial brass profile made flexible by milling. The pressure and heat break the profile into two, like the two pronged tail of a mermaid. Both parts open and are curved, hosting a flower in the middle. By using contemporary materials and techniques, Bianchi embraces a very ancient tradition: that which gives objects apotropaic functions and makes them symbols of fer- tility and vitality.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diario 03/20

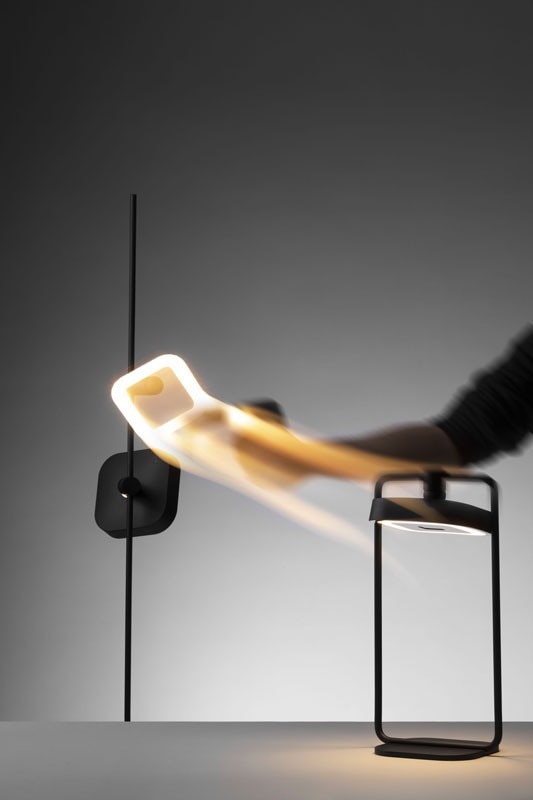

Federica Biasi

Federica Biasi, born in 1989, founded her design studio in Milan in 2015, dealing with product design, design consultancy and interior design. In 2017 she became art director of the Italian company Mingardo, while collaborating as creative consultant with design companies such as Fratelli Guzzini, focusing on research and forecasting trends worldwide: colour, materials and finishes. He also develops ceramic tableware and textile products, strongly believing in the strength of handcrafted products.

Guglielmo Brambilla

Normally, tiles are found on roofs. Lined in a row, they offer protection and shelter. Guglielmo Brambilla recontextualises them and, with a unique ready-made operation, transforms them into vases. His work method: discovering the story hidden in objects and allowing their emotional potential to surface. With Coppo, Brambilla takes a traditional Florentine tile, perforates it and then places it on a cylindrical stand in terracotta: the result is a crafted object that is both a vase and container for flowers. Starting with simple materials like bricks, tiles or shingles, Brambilla creates expressive uni- verses that turn the ordinary into the extraordinary. The design won second place at Montelupo Ceram- ic Award 2018 and was made in collaboration with Bitossi Ceramiche in fall 2019.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diario 01/20

Tip Studio

Lovers of craftsmanship and experimenting with materials, in their recent design, Secondo Fuoco, the young designers Imma Matera and Tommaso Lucarini have chosen to focus on the useless, on left-overs, on discards. In collaboration with the Fonderia Artistica Versiliese, these designers collect discards from the casting process; they then cata- logue them based on types, trim them into small fragments and, finally, pair and immobilise them with wax. They are then subject to further casting (a “second firing”) that creates new and unique objects: small material sculptures, each containing clashing elements (cold/heat, smooth/rough, shiny/ matt). In addition to cast bronze, elements in glass, marble and steel are also employed and paired, to accentuate the intentional material hybridisation that is at the heart of the entire design, poised be- tween art, artisanry and design.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diary 05/20

Giuseppe Arezzi

A multipurpose object to furnish a minimal living space: those tiny houses measuring a little over 10 m2 (the so-called chambres de bonne, or servants’ chambers), built in the attics of early 19th-century Parisian homes, today oftentimes occupied by students. Giuseppe Arezzi – Sicilian by birth, Milanese by choice – designed Binomio (edited by It’s Great Design by Margherita Ratti in Paris) precisely for this space, as the prototype of hybrid furnishing, with three shelves at three heights: it can turn into a desk or a dresser, but it can also be used for hanging clothes, or as a bench, a small table and even a kneeling-stool. Both rigorous and visionary, with a design approach deriving from careful social-anthropological analysis, Arez- zi belongs to that generation of designers who re-ex- plore ancient craftsmanship traditions in order to offer innovative solutions to the needs of contem- poraneity.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diary 04/20

Antonio Facco

Milanese, trained at the IED in Milan, among his collaborations we find Cappellini. Antonio Facco theorizes about the boundaries between art and design and explores the lesson of the design Masters, starting with Vico Magistretti, to decline it in today's landscape. His works range from product to interior.

Ilaria Bianchi

Her starting point is experimenting with materials. Ilaria Bianchi chooses antithetical ones, manipulating them so as to create multisensory engagement in the user. With Bicaudata, Bi- anchi makes a sort of small, slender and delicate vase, beginning with an industrial brass profile made flexible by milling. The pressure and heat break the profile into two, like the two pronged tail of a mermaid. Both parts open and are curved, hosting a flower in the middle. By using contemporary materials and techniques, Bianchi embraces a very ancient tradition: that which gives objects apotropaic functions and makes them symbols of fer- tility and vitality.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diario 03/20

Federica Biasi

Federica Biasi, born in 1989, founded her design studio in Milan in 2015, dealing with product design, design consultancy and interior design. In 2017 she became art director of the Italian company Mingardo, while collaborating as creative consultant with design companies such as Fratelli Guzzini, focusing on research and forecasting trends worldwide: colour, materials and finishes. He also develops ceramic tableware and textile products, strongly believing in the strength of handcrafted products.

Guglielmo Brambilla

Normally, tiles are found on roofs. Lined in a row, they offer protection and shelter. Guglielmo Brambilla recontextualises them and, with a unique ready-made operation, transforms them into vases. His work method: discovering the story hidden in objects and allowing their emotional potential to surface. With Coppo, Brambilla takes a traditional Florentine tile, perforates it and then places it on a cylindrical stand in terracotta: the result is a crafted object that is both a vase and container for flowers. Starting with simple materials like bricks, tiles or shingles, Brambilla creates expressive uni- verses that turn the ordinary into the extraordinary. The design won second place at Montelupo Ceram- ic Award 2018 and was made in collaboration with Bitossi Ceramiche in fall 2019.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diario 01/20

The youngest designers, for example, are expressing growing frustration with a standardised and homologated idea of design, at the same time rediscovering the functional and expressive potential of hand-made items and the arts, focusing on the uniqueness of objects or designs even when they are partially engineered or created digitally. Globalisation is showing signs of age, delocation is no longer beneficial, and Made in Italy can once again be both a promise and a guarantee instead of just a meaningless label or an easy marketing tactic. Now the spotlight is on a rethinking of economic and productive systems, and the redesigning of spaces, movements and relationships. There is an innovative attitude that is not far removed from that of the post-war period. At the time the focus was on reconstruction, now it is on invention and innovation. There are specific names on which to focus. They are inquisitive, free of dogma, they know how to navigate beyond the postulates of the past and they are not afraid to experiment and take risks. They are united by a common inclination for moving beyond confines and fostering hybridisation.

For example: Tip Studio takes waste and places it at the centre of design; Giuseppe Arezzi re-explores ancient artisan traditions for original solutions to the demands of modern life; Antonio Facco theorises on the grey area between art and design and explores the teachings of the Masters, beginning with Vico Magistretti, adapting them to the contemporary scene; Ilaia Bianchi uses modern materials and techniques to return to that age-old tradition that assigned apotropaic powers to objects, rendering them symbols of fertility and vitality; Federica Biasi brings together the far and the near, seeking to infuse her designs with meaning as well as function; beginning with humble objects such as bricks or tiles, Guglielmo Brambilla creates expressive universes that render the ordinary surprising and unexpected, in a similar manner to the work of Flatwig Studio rub by Francesca Avian and Erica Agogliati, who - through Ondula - create a collection of furnishings and accessories from corrugates sheets used to cover roofs.

View gallery

View gallery

Flatwig Studio, Francesca Avian and Erica Agogliati

Flatwig Studio's projects are very often born from the observation and study of past customs and folklore. The themes of food and tableware and the gestures associated with them are recurrent in their design and are a fundamental component of their practice. Avian and Agogliati, founders of the studio, select and choose materials in a responsible, sustainable and conscious way. Their works and projects have been presented in important publications and acclaimed for their fresh and international approach.

Flatwig Studio, Francesca Avian and Erica Agogliati

Milan Design Week, Alcova Sassetti, Milano, 2019

Flatwig Studio, Francesca Avian and Erica Agogliati

The Surreal Table, Milan Design Week, Palazzo Durini, Milano, 2018

Matteo Di Ciommo

He is a student of Michele De Lucchi, but his design choices call to mind the poetics of Aldo Rossi: taking architecture as a model and source of inspiration to create objects. In his project Piani, ripiani e terrazze Matteo Di Ciommo builds trays and stands, inspired by the lighthouses of Sardinia or certain castles perched on mountainsides in Italy. The roofs of houses or natural terraces thus become flat sur- faces while trays turn into domestic landscapes. The collection offers eight pieces, all unique, in walnut, cherry and mahogany wood: the object be- comes a sculpture and the design based on self-production combines with the ancient knowledge of high artisanry.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diario 03/20

Sara Ricciardi

Sara Ricciardi, a multifaceted designer, works with an approach characterized by narrative exploration: each aesthetic is born as a result of a precise story. Materials and processes are defined each time with the help of great masters of Italian craftsmanship. She is an excellent collector of bizarre objects. She opened in January during Pitti 2019 her first concept store called "Eden", thus opening an interior design project for the launch of the Attico brand capsule collection at the Luisa Via Roma high fashion store in Florence.

Andrea De Chirico

Andrea de Chirico, born in Rome and based in Milan, concentrates on the intersection between conventional, traditional and modern making. He designs instruments, systems and objects with a social and environmental sensitivity, always linked to a rigorous analysis of the context. His studio is open and accessible, creating a platform to connect with different groups at an international level, reshaping everyday products for different contexts.

Mais Project, Matteo Mariani and Isato Prugger

MAIS Project is a creative studio founded by Matteo Mariani and Isato Prugger. Based in Monza, it operates through product design and strategic planning consultancy. The studio develops innovative solutions for sturtups, and for new realities willing to get involved. Innovation, for them, is the constant contamination between all the stakeholders of the experience: clients, clients and collaborators.

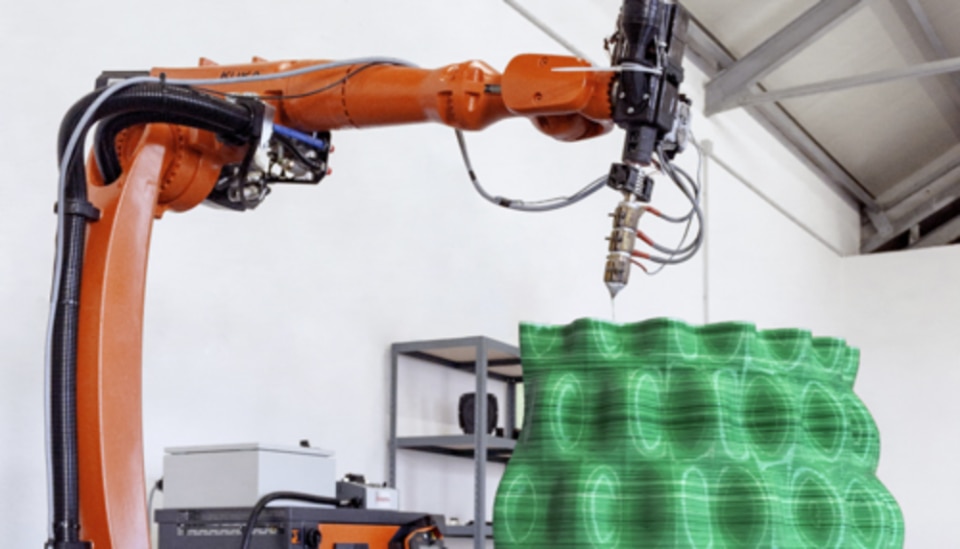

Caracol Studio, Giovanni Avallone, Jacopo Gervasini and Paolo Cassis

Caracol is the initiative of Giovanni Avallone, Jacopo Gervasini and Paolo Cassis, who tries to overcome, with their team, the limits of traditional 3D printing by offering advanced and customized design and production solutions for different sectors. With their Additive 4.0 Manifttura Additiva Pole they offer different solutions: product redesign and concept development, large-scale prototypes, in-line production of finished parts, support in the creation and remote management of new AM clusters at the customer's premises, training and 3D printing workshops.

Flatwig Studio, Francesca Avian and Erica Agogliati

Flatwig Studio's projects are very often born from the observation and study of past customs and folklore. The themes of food and tableware and the gestures associated with them are recurrent in their design and are a fundamental component of their practice. Avian and Agogliati, founders of the studio, select and choose materials in a responsible, sustainable and conscious way. Their works and projects have been presented in important publications and acclaimed for their fresh and international approach.

Flatwig Studio, Francesca Avian and Erica Agogliati

Milan Design Week, Alcova Sassetti, Milano, 2019

Flatwig Studio, Francesca Avian and Erica Agogliati

The Surreal Table, Milan Design Week, Palazzo Durini, Milano, 2018

Matteo Di Ciommo

He is a student of Michele De Lucchi, but his design choices call to mind the poetics of Aldo Rossi: taking architecture as a model and source of inspiration to create objects. In his project Piani, ripiani e terrazze Matteo Di Ciommo builds trays and stands, inspired by the lighthouses of Sardinia or certain castles perched on mountainsides in Italy. The roofs of houses or natural terraces thus become flat sur- faces while trays turn into domestic landscapes. The collection offers eight pieces, all unique, in walnut, cherry and mahogany wood: the object be- comes a sculpture and the design based on self-production combines with the ancient knowledge of high artisanry.

Silvana Annicchiarico, published on Domus, Diario 03/20

Sara Ricciardi

Sara Ricciardi, a multifaceted designer, works with an approach characterized by narrative exploration: each aesthetic is born as a result of a precise story. Materials and processes are defined each time with the help of great masters of Italian craftsmanship. She is an excellent collector of bizarre objects. She opened in January during Pitti 2019 her first concept store called "Eden", thus opening an interior design project for the launch of the Attico brand capsule collection at the Luisa Via Roma high fashion store in Florence.

Andrea De Chirico

Andrea de Chirico, born in Rome and based in Milan, concentrates on the intersection between conventional, traditional and modern making. He designs instruments, systems and objects with a social and environmental sensitivity, always linked to a rigorous analysis of the context. His studio is open and accessible, creating a platform to connect with different groups at an international level, reshaping everyday products for different contexts.

Mais Project, Matteo Mariani and Isato Prugger

MAIS Project is a creative studio founded by Matteo Mariani and Isato Prugger. Based in Monza, it operates through product design and strategic planning consultancy. The studio develops innovative solutions for sturtups, and for new realities willing to get involved. Innovation, for them, is the constant contamination between all the stakeholders of the experience: clients, clients and collaborators.

Caracol Studio, Giovanni Avallone, Jacopo Gervasini and Paolo Cassis

Caracol is the initiative of Giovanni Avallone, Jacopo Gervasini and Paolo Cassis, who tries to overcome, with their team, the limits of traditional 3D printing by offering advanced and customized design and production solutions for different sectors. With their Additive 4.0 Manifttura Additiva Pole they offer different solutions: product redesign and concept development, large-scale prototypes, in-line production of finished parts, support in the creation and remote management of new AM clusters at the customer's premises, training and 3D printing workshops.

Then there are those who take on the role of attentive observers of daily life, even of its most marginal aspects, such as Matteo Di Ciommo or the exuberant Sara Ricciardi, who creates sensual objects that walk the line between crafts and industry while also practising social design and taking a stance as a “social aviator”, helping citizens to overcome the dilapidation and squalor of abandoned places, or those of the likes of Andrea de Chirico, who through a politically aware approach seeks to create networks of designers who share small locally produced products while aiming at addressing the world.

All this without forgetting those that work on innovating processes and technologies, such as the Mais Project firm run by Matteo Mariani and Isato Prugger, or Giovanni Avallone, Jacopo Gervasini and Paolo Cassis’s Caracol Studio, who - with their Additive Manufacturing 4.0 Centre - present themselves as a paradigm for the new direction that design has taken in recent years, through research, experimentation and contamination. There is a challenge that awaits all of these figures, which is to emerge from the emergency by designing objects, processes, furnishings and venues that better protect health, safety and sustainability without foregoing beauty or sacrificing sociality.