The opening of the new Moynihan Train Hall on 1 January of this year has rightly been hailed as a dramatic improvement in rail passenger service and a notable addition to the civic realm of New York City. Because the new space was constructed within the Beaux-Arts shell of the James A. Farley Post Office building, which was designed, like the lamented, original Pennsylvania Station, by McKim, Mead & White directly across Eighth Avenue, it seemed to many New Yorkers to have been conjured overnight and became an Instagram-able site within days of opening.

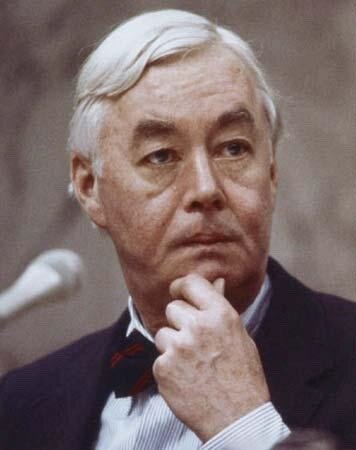

Moynihan Train Hall – named in honor of the late New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who championed the project beginning in the 1990s – also vindicates the muscular role of government in addressing a range of pressing needs. Empire State Development, the State’s economic development authority, and Governor Andrew M. Cuomo, in partnership with MTA Long Island Rail Road, Amtrak, and real estate developers, have driven the project to completion. It is an occasion to reassess the role of this major transportation complex in the urban fabric of the city over the last century and to understand the possible futures latent in this project.

The interplay between passenger rail transport and urbanism in New York City has unfolded very differently than in the great European metropolises. While the New York regional rail network is the most developed in the US, it is not nearly as robust as those of Paris or London. It could be argued, however, that the early 20th-century transportation solutions of Pennsylvania Station and Grand Central Terminal were more seamlessly integrated into the urban fabric of the city. The original transport vision of Penn Station in particular has set the stage for significant growth in the coming decades.

Penn Station and the city in the 20th century

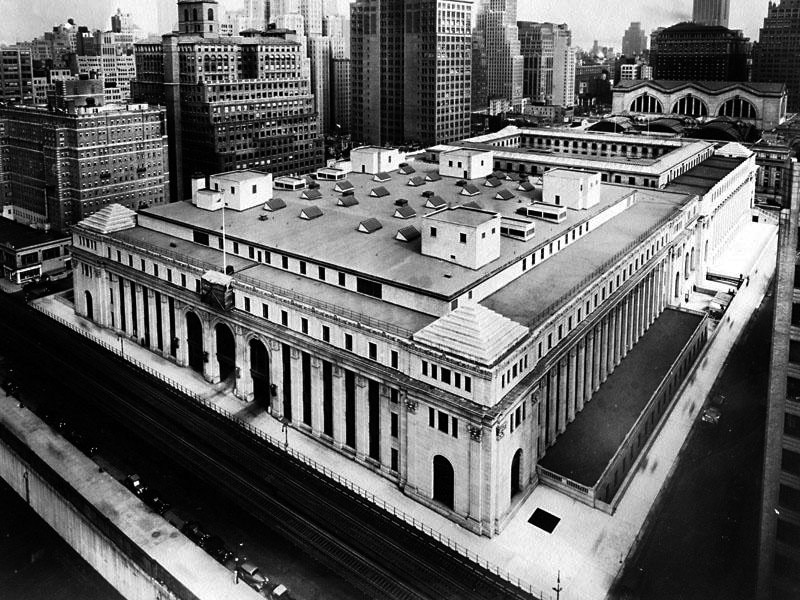

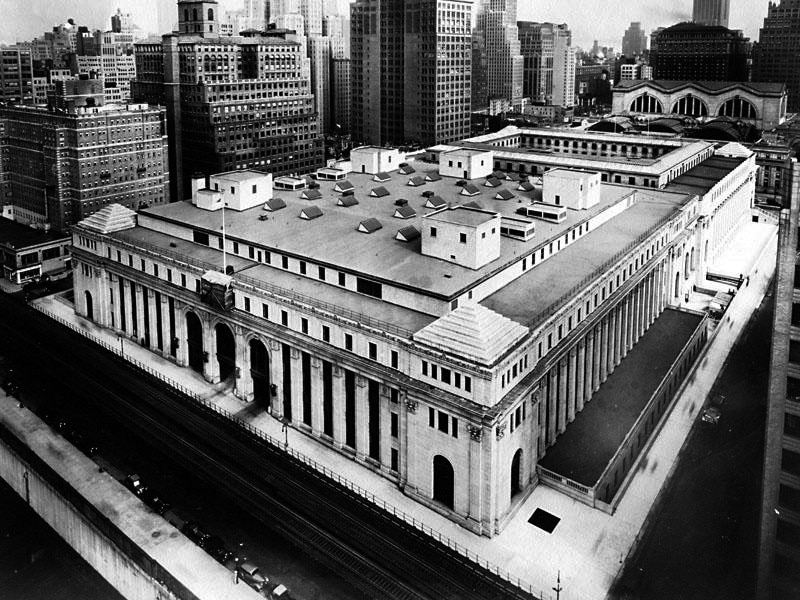

By the end of the 19th century, the Pennsylvania Railroad Company was one of the largest and most powerful corporations in the United States. But its trains bound for New York terminated in Jersey City, New Jersey, where riders boarded a fleet of ferries that made the crossing to Lower Manhattan. For the new station, the company selected a site in Midtown West that could potentially be more central to the city as a whole. But in doing so, they committed to limiting the extent of the station building above ground to the blocks of the street grid, which had been established in 1811 and thoroughly built out by 1900. In Europe, the great 19th-century rail terminals were added at the edges of cities, or partially implanted into the borders of the denser urban fabric, with sprawling railyards and service buildings. In New York City, both Grand Central Terminal and Penn Station had to conform to the Manhattan grid. In the case of Penn Station, the breadth of the 21 tracks extended under 31st Street to the south and 33rd Street to the north, but the street grid kept the station complex within a rectangular perimeter. The railroad did, however, manage to acquire the right of way of 32nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues.

Transport facilities and the urban realm must be mutually reinforcing

Not only the hard and fast planning constraints of the block dimensions, but the nature of the marginal district of the new station conditioned its role in the city throughout the 20th century. The need to sink the tracks in deference to the public streets also laid the groundwork for the immense potential the station holds more than a century later. The new station, designed by the great New York firm of McKim, Mead & White, and under the leadership of Charles Follen McKim himself, took some architectural cues from European rail stations and notable ancient precedents, such as the Roman baths, Egyptian and Greek hypostyle structures and others, but was brilliantly resolved with the rail facilities 45 feet below street level and the intricate circulation systems for passengers, service vehicles and baggage. The Pennsylvania Railroad company was confident the new station would lift up the district, a neighborhood with a reputation that the New York Herald once described as a “famous home of vice and blackmail,” and lead to upscale commercial development compatible with the grand station. The company had reason to believe Penn Station would be served by the new underground subway systems that were replacing the elevated lines in Manhattan. It is astonishing to think that the subway lines under Seventh and Eighth Avenues were opened in 1918 and 1932, respectively, although the architects’ design of the station had provided direct connections to both lines. When Penn Station opened in 1910, it was served only by low-capacity trolley services.

Other attempts were made to catalyze development of the area broadly and to create a compatible setting in the immediate vicinity. The station’s urban plan called for two new mid-block streets to be cut on axis with the grand waiting hall. The one cut through to the 34th Street thoroughfare was particularly important. McKim proposed a widening of 32nd Street from Greeley Square that would be lined with arcaded buildings inspired by European models. Alas, the railroad only controlled part of the block and the concept never advanced. The US General Post Office, later renamed the Farley Building, was the only piece of a possible vision for the district that got built, but it was located to the west of Eighth Avenue over the tracks, in order to load mail directly onto trains. The design of the Farley Building, also by McKim, Mead & White, is thoroughly complementary to the Beaux-Arts design of the Station. It is within this structure that Moynihan Train Hall was designed and constructed some 110 years later. The subsequent Post Office Annex, also designed by the McKim firm, was added in the 1930s and extended a broadly cognate Beaux-Arts language to Ninth Avenue.

Meanwhile, Grand Central Terminal had been rebuilt in the years 1903-1913 by the New York Central Railroad Company very much with the emerging Penn Station in mind. Broad analogies between the two structures can be drawn. In each case the tracks were lowered and the passenger building stands proud in its urban setting, astride an avenue or street but otherwise bound by the Manhattan grid. Each station was a tour de force of architectural design, rail engineering, and complex multi-modal and pedestrian circulation systems, all interwoven into an architectural environment that was both easy to navigate and uplifting.

But that’s where the comparisons between Penn Station and Grand Central end. Midtown East was already a desirable district for apartments and office buildings, and the buildout of the lots over the tracks along Park Avenue proceeded swiftly and according to an innovative plan dubbed “Terminal City,” while the area around Penn Station languished. The contrast was apparent at the time to both the public and the railroads. The Pennsylvania Railroad was only able to modestly influence its setting. Apart from the post office, its only other joint venture was participation in the development of the Hotel Pennsylvania, also designed by McKim, Mead & White in a compatible style and with its lot line set back in deference to the station across Seventh Avenue. The later office building south of 32nd Street, known today as 11 Penn Plaza, respected the hotel’s setback and was broadly sympathetic in style to the station. These are the fragments of a designed context for the lost Penn Station.

Despite the failure to move confidently into the real estate business and to shape a district worthy of its original transportation role, Penn Station’s tragic demise in 1963 was in truth a result of the emergence of the automobile, the interstate highway system and commercial air travel. Some sixty years on, as the carbon impact of those modes of travel have come under scrutiny in the 21st century, intercity and commuter rail transport are seen as key parts of a response to climate change. The corresponding renaissance of New York and other cities over the last generation has created conditions that complement the opportunities in mobility.

Fulcrum of transportation and urban transformation

Moynihan Train Hall’s design, transport function and urban role are emblematic of the present time in the city’s history.

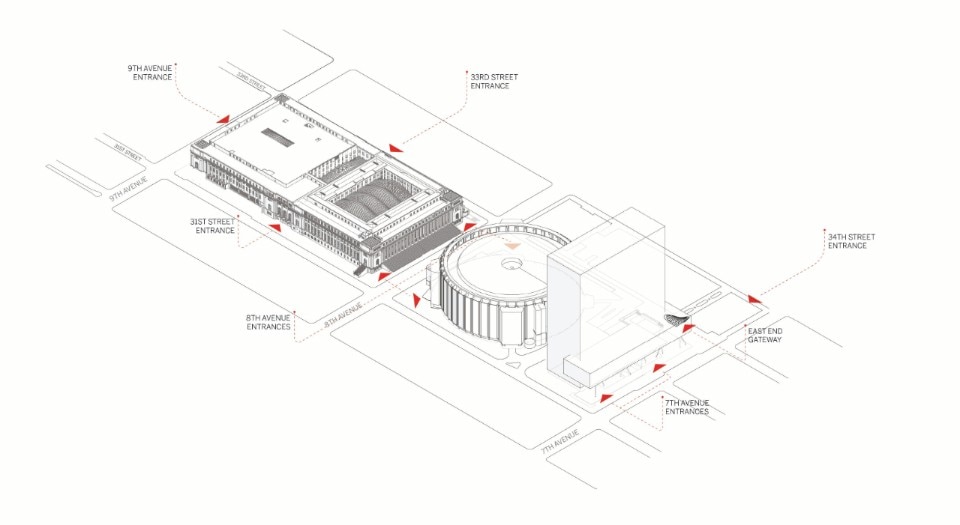

Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) was selected through a competitive process in 1997 to design the new station within the fabric of the historic post office building. Over the course of two decades, SOM worked on various schemes to trans form the structure into a modern rail station—ultimately leading the multidisciplinary design team for the successful iteration of the project, which began construction in 2017, and established the iconic new home for the Long Island Rail Road and Amtrak. The design quite intentionally strikes a balance between the three poles of historic preservation, adaptive reuse and technically advanced architecture and engineering.

The exterior of the historic post office structure has been treated largely as a precious artifact. Selective changes, such as opening entrances to each side of the monumental staircase on Eighth Avenue, as well as at the former mid-block loading zones, will likely be perceived as original by most users. Similarly, within the Train Hall itself, a delicate operation of selective editing, removals and adjustments were necessary to thread the complex pedestrian movement systems service functions into what had been an urban and factory of mail handling. The original mail sorting floor was removed so that the lower floor could serve a Train Hall of appropriate amplitude. The trussas traversing the entire space were restored to display their brute functional role. All other elements necessary for an operating station – escalators to the train platforms, ticketing and baggage areas, waiting lounge and concessions spaces – are of a sleek, contemporary design that harmonizes with the original industrial elements without falsely replicating them.

It is in the new skylights overhead that we see an architecture entirely of our time. The billowing lightweight diagrid steel frames holding clear glass panels are a feat of architectural engineering, structural design and detailing. Like upturned spinnakers, they expand the impression of the Train Hall volume and admit copious daylight into the gathering space below. The project also opened up the midblock access points and capped the space with a similar vaulted skylight, setting up connections to the surrounding streets and through the repurposed Farley Building Annex to the west.

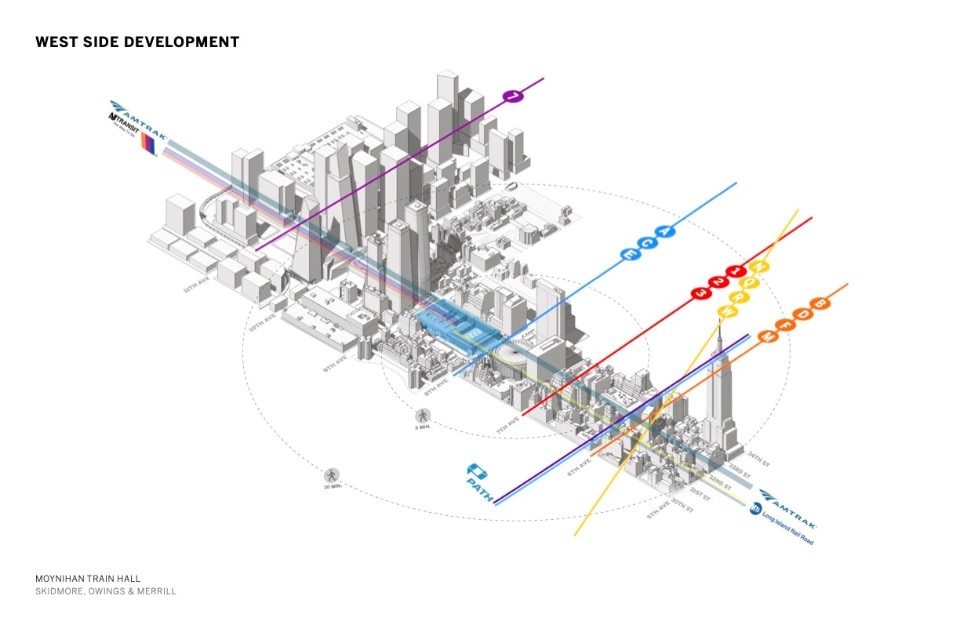

While Moynihan Train Hall passed through several stages of design, financing, and false starts in the early 2000s, the area to the west of Penn Station saw new development on a massive scale. To the west, toward the Hudson River, the Hudson Yards and Manhattan West developments have been predicated to some extent on Moynihan Train Hall and the growth of Penn Station’s rail service.

It would not have been possible without the preponderant role of the public sector

In very practical terms, these developments were made possible by an innovative structural solution of “overbuild,” the construction of a platform over the station’s extensive rail yard and train storage areas. A 21st-century version of the device that led to the development of Park Avenue north of Grand Central Terminal was finally deployable west of Penn Station. The western half of the massive Annex building is being developed as a mixed-use office and retail complex directly connecting to Moynihan Train Hall. New Yorkers and commuters will be able to enter the Penn Station complex through an impressive new portal at Seventh Avenue and 33rd Street – a project also driven by Governor Cuomo and designed by SOM – where they can pass through a renovated corridor of Penn Station, cross under Eighth Avenue to enter Moynihan Train Hall and exit onto Ninth Avenue through the new mixed-use center.

From there, a network of pedestrian plazas at Manhattan West leads to the Hudson Yards complex and the High Line elevated park. The urban realm around the station will achieve the connectedness and vibrancy sought by the leadership of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company a century ago. If Moynihan Train Hall has been the catalyst for these developments, it is also the fulcrum upon which a quantum leap in both transport and urban development in the coming decade turns.

New York’s cross rail and the next stage

We don’t always pause to recognize that Penn Station is just that – a station – and not a terminus.

The tracks continue under Midtown Manhattan and the East River and rise to loop north on a great rail viaduct in Queens on their way to New England. Since its opening more than 100 years ago, the tunneled line through the city has been that holy grail of rail service, a “cross rail” that several European cities are only now planning or constructing at huge expense to allow through-running rail traffic and to eliminate the cumber some inter-terminal transfers from one side of the city to the other. By purchasing control of the Long Island Rail Road in 1900 and constructing what was then called the New York Connecting Railroad from Sunnyside in Queens to the New Haven Line in the Bronx, the Pennsylvania Railroad positioned Penn Station at the center of an inter-regional rail network. The visionary nature of this concatenation of projects should inspire us today. It is worth noting that all of the original complex was a privately financed undertaking. Moynihan Train Hall would not have been possible without the preponderant role of the public sector that established and led an innovative public-private partnership. Future projects will require collaboration on a colossal scale. Expansion of passenger rail capacity to Penn Station and Moynihan Train Hall through new tunnels under the Hudson River has been planned for decades and seems to be on the verge of coming to fruition. We should hope and advocate for a coordinated plan that allows the transport facilities and the urban realm to be mutually reinforcing and to constitute another transformational enhancement of life in New York City.