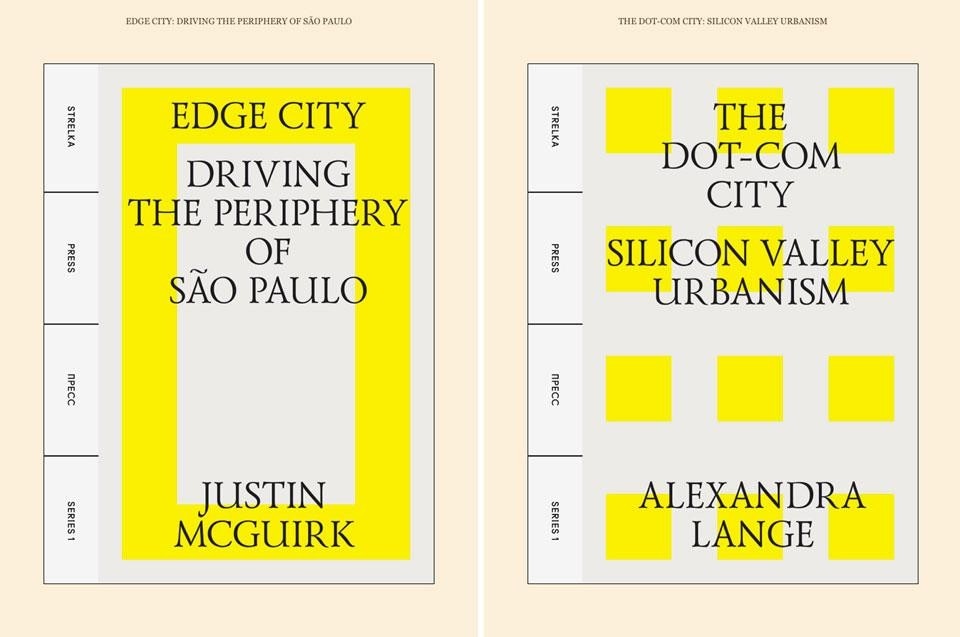

Justin McGuirk, Edge City. Driving the Periphery of São Paulo, Strelka Press, Moscow 2012, 955 KB

This article was originally published in Domus 961 / September 2012

Both Alexandra Lange and Justin McGuirk's e-books for the newly founded publishing house founded by the Strelka Institute — for which McGuirk is publishing director — are tales of divided cities, critiques of the lack of government or corporate responsibility for city making leading to polarised outcomes, which according to the authors waste opportunities for positive change. In both cases, the authors embark on a critical dérive, necessarily by car, exploring these isolated, disjointed communities, speculating at the same time on the lack of political will to regenerate the downtown.

Lange argues that both the city and the dot-coms have a lot to gain by applying some of the creativity they engage with to build online technology empires to engagement with the space between the metropolis and their inward-looking suburban enclaves. She draws on Louise Mozingo's Pastoral Capitalism: a history of suburban corporate landscapes (MIT Press, 2011) to support many of her points, maybe too heavily. Both agree on the unsustainability of the suburban corporate architecture, but while Mozingo's objections are about reliance on the car, Lange's case study underpins a bigger protest: dot-coms promote city campus zones free of public realm, that elusive space of difference. Unwrapping her points from her ample descriptions of their corporate locales, the reader gradually gets drawn into her polemic about their enclavism and at what cost it comes to the spatial identity of the civic as a concept.

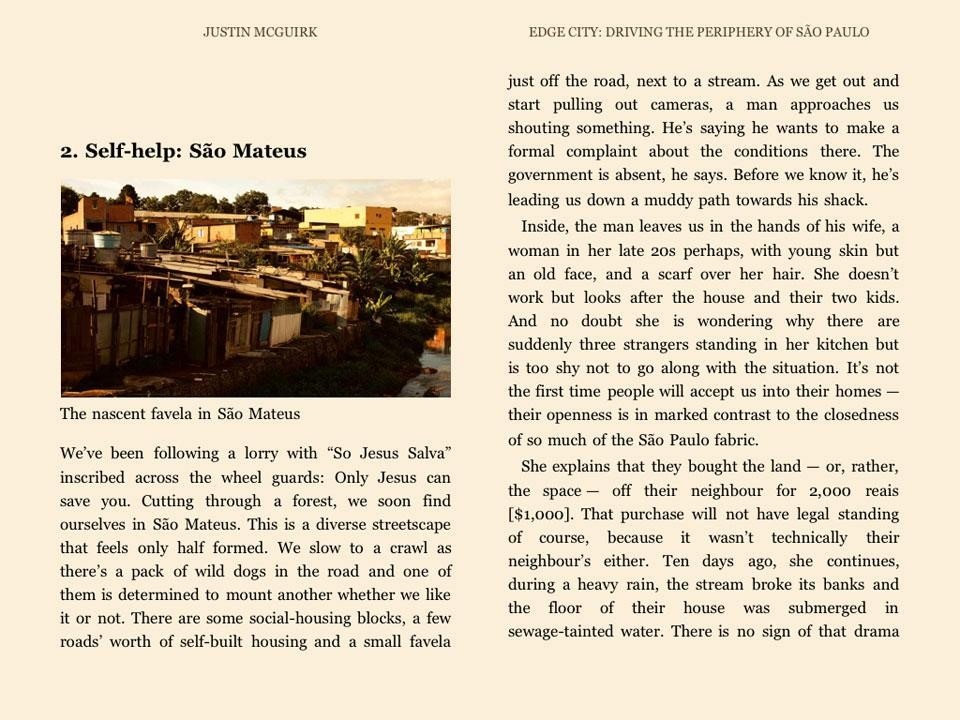

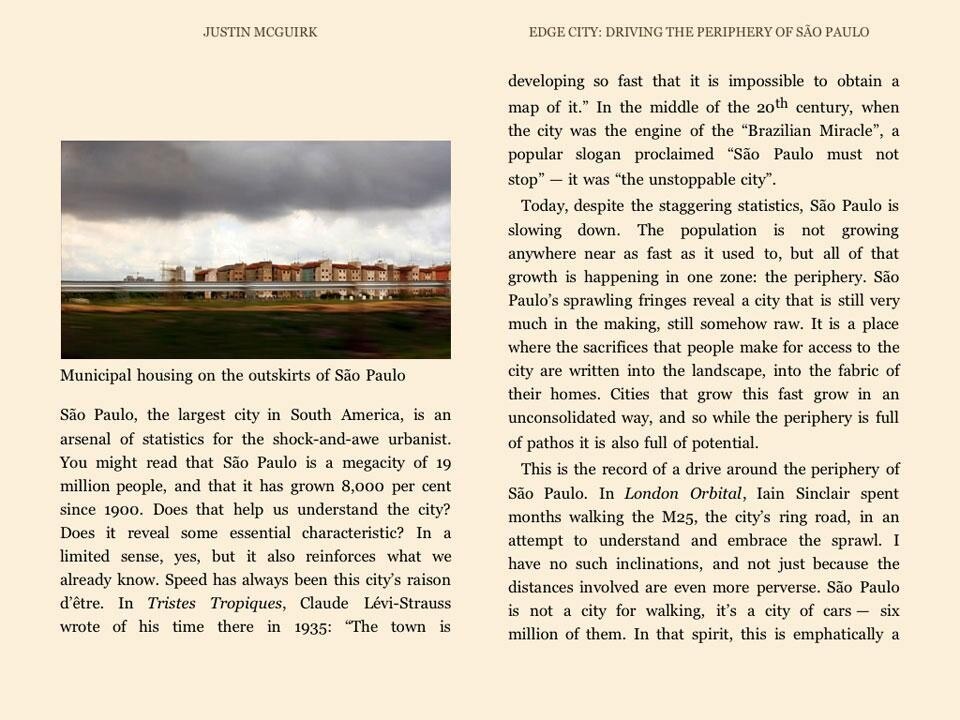

That could be because the point of his e-book is to argue why the informal city cannot be incorporated into the formal city through better transport, infrastructure and employment. McGuirk worries about the status of the favelas, suffering actual and threatened evictions in the lead up to the 2014 World Cup; the legacy of successive mayors pandering to the real estate lobbies that fund their campaigns rather than come up with a vision for the periphery. What is the formal city? Impeded by traffic-clogged roads, the author finally makes it to Alphaville, one of the largest gated communities in the world. Planned in the mid-1970s, this is a town ringed by a steel fence topped by barbed wire, concealing neat streets of mansion houses with swimming pools. But this isn't the formal city, and nor is "formal" entirely defined by the historic centre, seen as either in decline or enjoying a new quarter, Nova Luz, with a cultural centre by Herzog & de Meuron.

Typifying a new genre of polemical writing about the city and its evolution, about how civic aspirations should avoid being swallowed by corporate and real estate interests, both e-books valuably open up major debates about the future of urbanism and the kind of game-changing it can effect in the 21st century

There are amusing insights gleaned from each journey. Along the way McGuirk spots an image of the model Jesus Luz, erstwhile boyfriend to Madonna, posing like Rio's statue of Christ the Redeemer in an advert for boxer shorts — there are a few black and white shots from the car in his e-book, while Lange's is unillustrated. But the deifying symbols of retail, while diverting, are not an answer to the condition McGuirk diagnoses.