Mark Shepard, ed. MIT Press, 2011. (200 pp. PB, US $24.95)

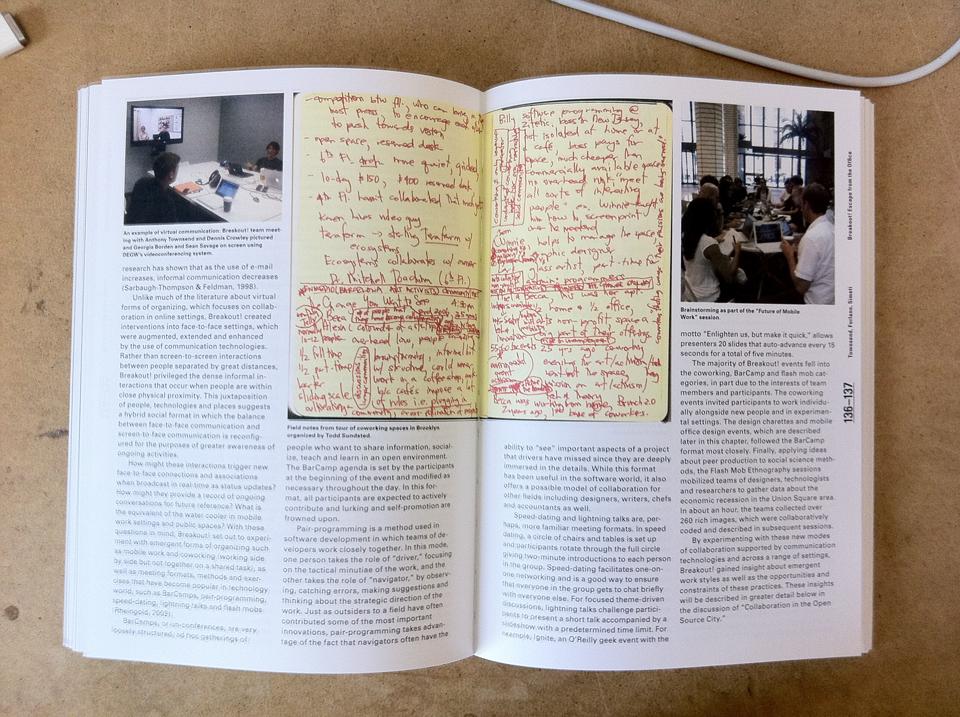

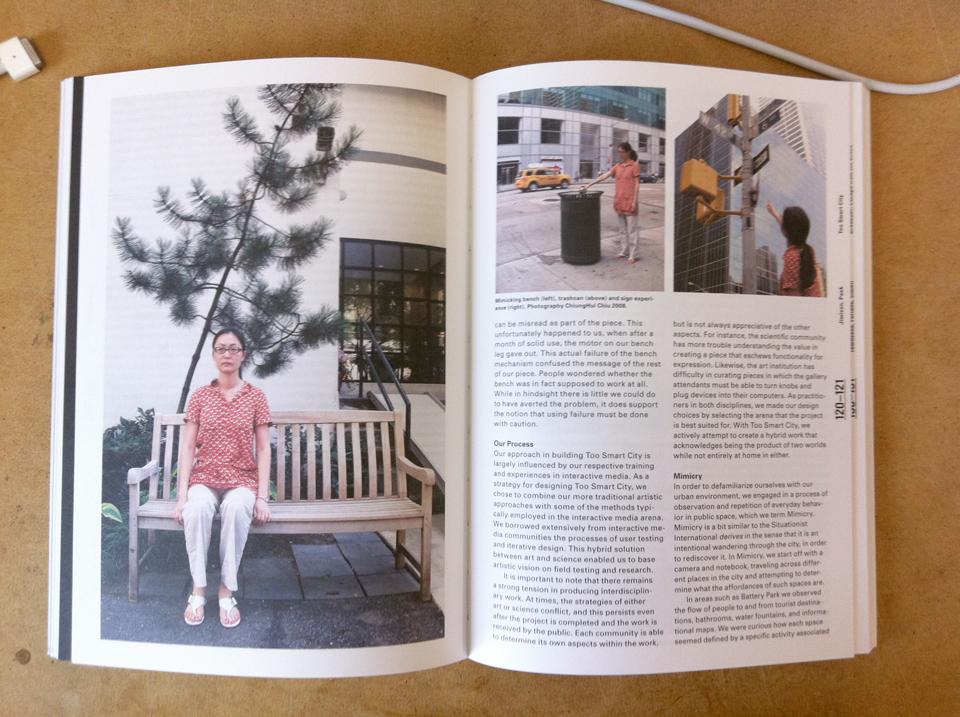

Sentient City: Ubiquitous Computing, Architecture, and the Future of Urban Space is the bibliographic product of a several-year-long conversation that has traversed physical sites and publication venues. It all began in 2006 with the "Architecture and Situated Technologies" symposium organized by Mark Shepard and multiple individual and institutional partners, including the Architectural League of New York. The gathering focused on the critical roles that networked digital technologies play in shaping the urban environment—roles that "challenge [those] traditionally played by architects," who, if they are to be actively involved in directing the evolution of the networked city, "must insert themselves now into the discussion of how these technologies are conceptualized and deployed" (Wessner 9). Many symposium participants later contributed to the Situated Technologies Pamphlet Series, and then collaborated again in 2009 in organizing the Toward the Sentient City exhibition at the Urban Center in New York.

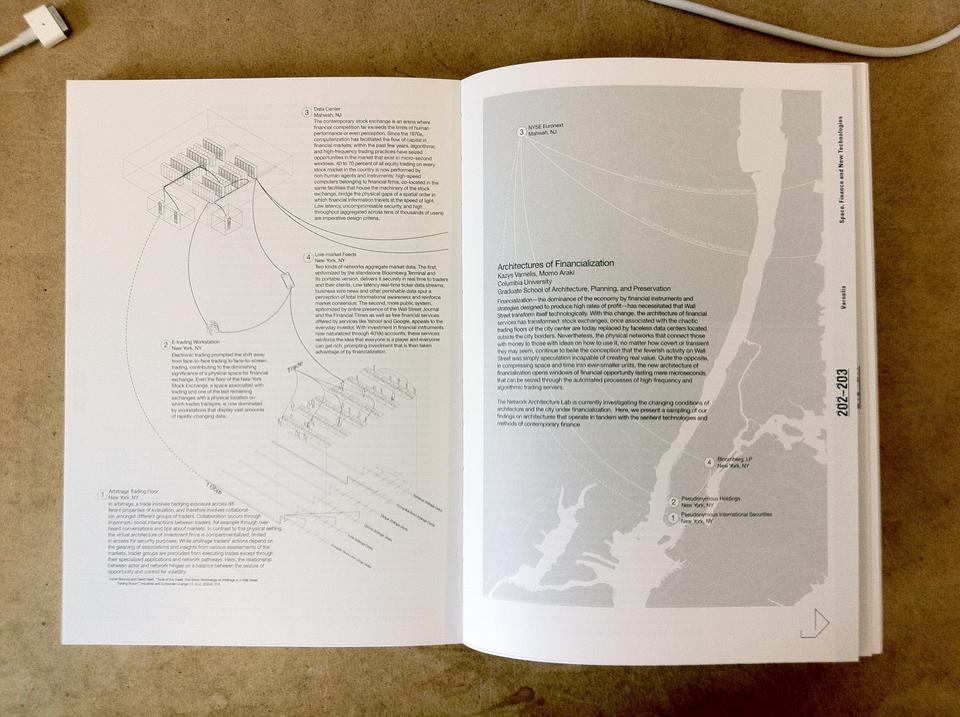

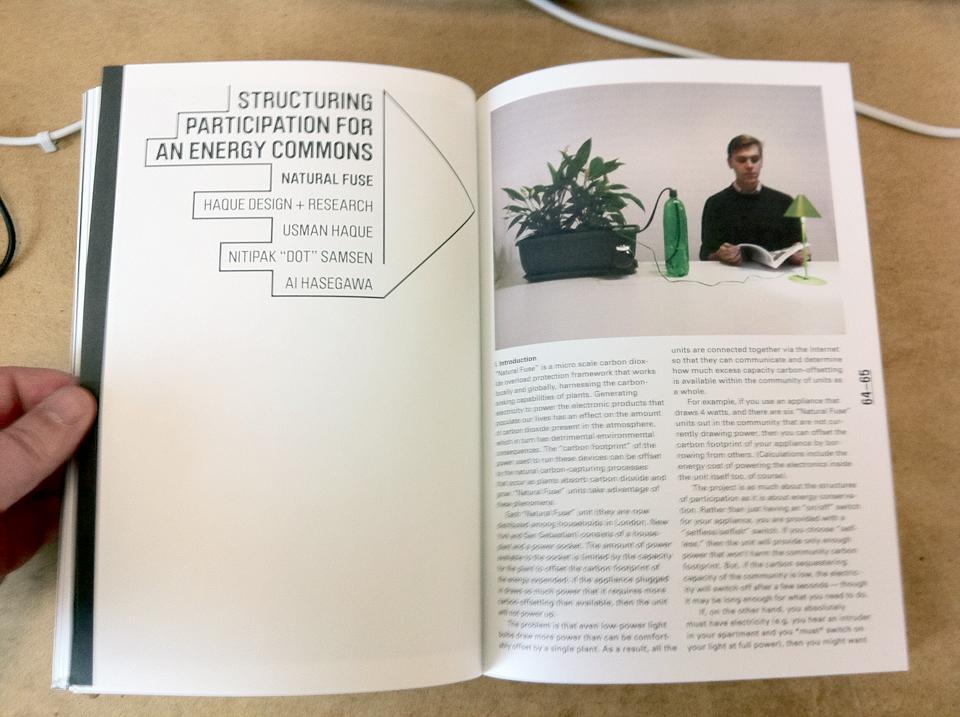

The projects on display at the exhibition are featured again in the book, but here they're "put…in[to] theoretical context" via essays by Shepard and other "prominent thinkers"—from Keller Easterling and Saskia Sassen to Matthew Fuller and Kazys Varnelis. In his introduction, Shepard, both exhibition curator and book editor, proposes that the volume is "less concerned with projecting near-future urban conditions than providing concrete examples in the present around which to organize a public debate on just what kind of future we might want" (14). That debate involves questioning the "implications of calling a city 'sentient'" (31). What does it mean to say that this is a place that "feels you, but doesn't necessarily know you"? (31) What does it mean to anthropomorphize spatial objects, to attribute agency to inanimate things, to assume that urban sentience translates into urbanite engagement? Both the case studies in the book's pages and the book-object itself, with its heat-sensitive cover, are what Lévi-Strauss might have regarded as bonnes à penser, goods to think with—goods with which to think about the future of the city, the future of situated technology, and architecture's potential contribution to both.

Shepard wonders if the profession can 'engage a form of practice that no longer places the act of making buildings as the central and defining role of the architect?'. It must, if architects are to be involved in shaping our networked urban futures.

We are left wondering, as we peruse the "Essays," how each author might be conceptualizing "sentience," and what he or she believes to be at stake: how do object sentience and human sapience converge when decisions are made regarding the design and deployment of new urban technologies? Thinking through the case studies' concrete examples of possible urban developments, and the sentient city as it is discursively constructed through this book, raises a larger question: what is the episteme of this urban sentience? What are the relationships between discourses of technological development, urban design, architecture, research methodology, data visualization, and other practices that collectively contribute to the creation of the sentient city—and how do they structure how we know the city and urban experience? What does it mean to employ inductive, data-driven methodologies to produce spaces that activate efficient urban actions, or, in Anne Galloway's words, "transmit the right kinds of urban experience"? (222). What, and who, is "right" in the sentient city? Do data decide? Because Sentient City offers little help in the way of thinking across the theoretical discussions in its "Essays" section, or thinking through the "Case Studies" via those essays, it relies heavily on the sapience of its readers to extract productive questions to frame "a public debate on just what kind of [an urban] future we might want."