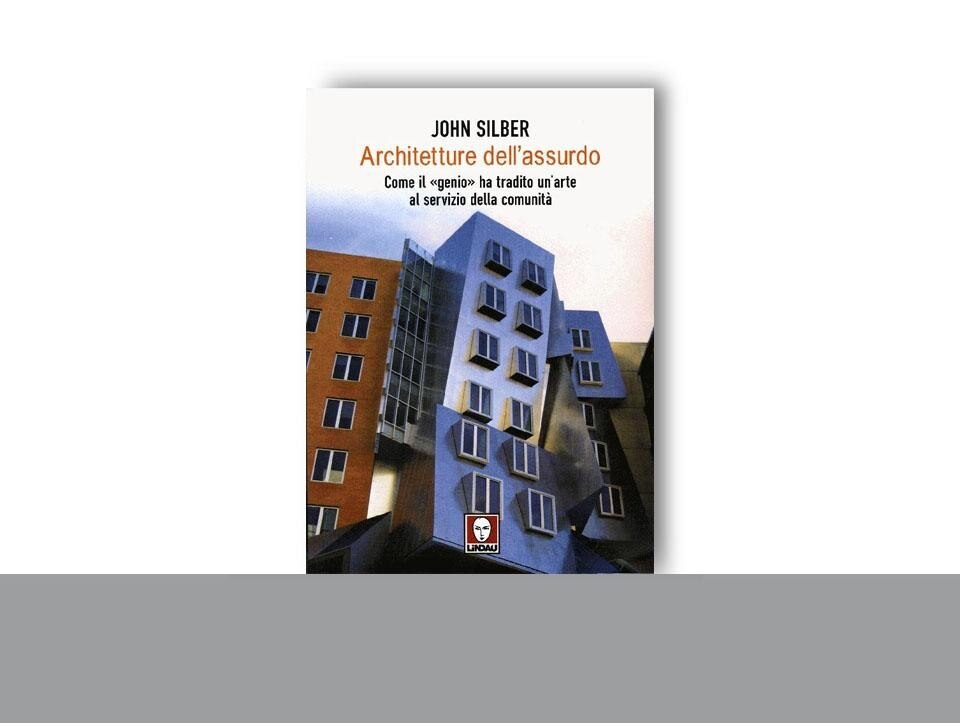

The archistars have become the target of public opinion in many parts of the world. Of late, controversy hasn't just stopped at the odd pungent newspaper article or some brilliant cultural provocation. Alongside ideal debates we are seeing the first legal action for design errors, such as MIT Cambridge's recent attack on Frank O. Gehry. The prestigious American university had asked him to design the Ray and Maria Stata Center, an academic complex of approximately 40,000 square metres that was quite literally leaking just one year after it had opened. It was probably in the wake of these events that John Silber wrote his ruthless portrait of the discipline in 2007, entitled Architecture of the Absurd and translated into Italian in early 2009.

Perhaps the most striking fact is that Silber, embraced by the architectural community as their honorary representative, has never practised as a professional architect. Born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1926, a professor of philosophy and law, and a prolific freelance journalist appearing in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, he was the President of Boston University from 1971 to 1996 and its Chancellor from 1996 to 2003. His extensive experience commissioning architecture for the Boston campus and his position as an apparent outsider to the professional world have enabled him to understand the knotty problems of contemporary architecture better than any specialist.

Silber reminds us that there is nothing new about the claim of originality that distinguishes the work of famous architects. An illuminating precedent can be found in Le Corbusier's plans for Algiers and the idea of razing the North African city's old centre to the ground to make way for a set of skyscrapers and housing complexes whose scale would have outshone those built by the Soviets. The harshest criticism is reserved for Josep Lluis Sert, the Catalan architect called to design numerous university buildings in Boston. According to Silber, Sert's disregard for local climatic conditions had disastrous repercussions for campus life, ranging from water infiltration to inadequate thermal insulation, costly maintenance and the absurdity of a Spanish-style patio in the student centre of snow-covered Boston.

Many of the questions Silber puts to the architectural establishment are disarming. For example, why do the essentially identical slanted cuts in the walls of the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the diagonal ones in the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto indicate two completely different things according their designer Daniel Libeskind: the Jewish locations in the German capital and the signs of the primacy of participatory space and public choreography in the Canadian city? Silber points out that the shiny stainless steel curves of the Disney Opera House's external structure in Los Angeles, dazzling its neighbours and raising the temperature in their apartments by nine degrees, necessitated the application of a costly cladding to the walls, resulting in a second-rate appearance that has completely distorted the character of the original project.

Although at first glance Silber's hatchet-job observations may seem naive and open to accusations of conservatism, the voice of this 80-year-old man living in Boston is by no means isolated. In Italy, for example, his criticisms are echoed in the recent publication of Contro l'architettura ("Against Architecture"), a pamphlet by the anthropologist Franco La Cecla from Palermo. On closer examination, these reflections fall into the cultural framework of a longstanding critical tradition of modern architecture, which first appeared in the United States and England between the late 1970s and early '80s. Inaugurated by Tom Wolfe with the venomous and famous From Bauhaus to our House, published shortly before Prince Charles made his famous and controversial London speeches on designs in the British capital about to be approved, this movement of opinion found further space in the writings of the mathematician and town planner Nikos Salingaros, the American sociologist Nathan Glazer, and the English philosopher Roger Scruton. Echoes of the debate were not lacking in Italy either. During the country's 2008 electoral campaign, and after Vittorio Sgarbi and Silvio Berlusconi's negative stance on Libeskind's designs for the ex-Milan trade fair complex, the discussion involved Meier's controversial Ara Pacis Museum. There was also a convergence on the activities promoted by CESAR (Centro Studi Architettura Razionalista), animated by Fabio Rampelli (a PdL member of Parliament) and the public forums and blogs promoted by websites such as Stefano Borselli's Il Covile and Giorgio Muratore's Archiwatch.

Many of the criticisms in Architetture dell'assurdo are merely common sense, but they are expressed with convincing simplicity and force. Silber hits the mark when he reflects on why architects feel the necessity to justify their work in an extreme attempt to make their choices seem less arbitrary. They resort to a pretentious and high-flown language, crammed with ideology and historic precedents in the frantic search for a noble pedigree. A real work of art, argues Silber, ought to speak alone without the need for complicated theoretical formulations.