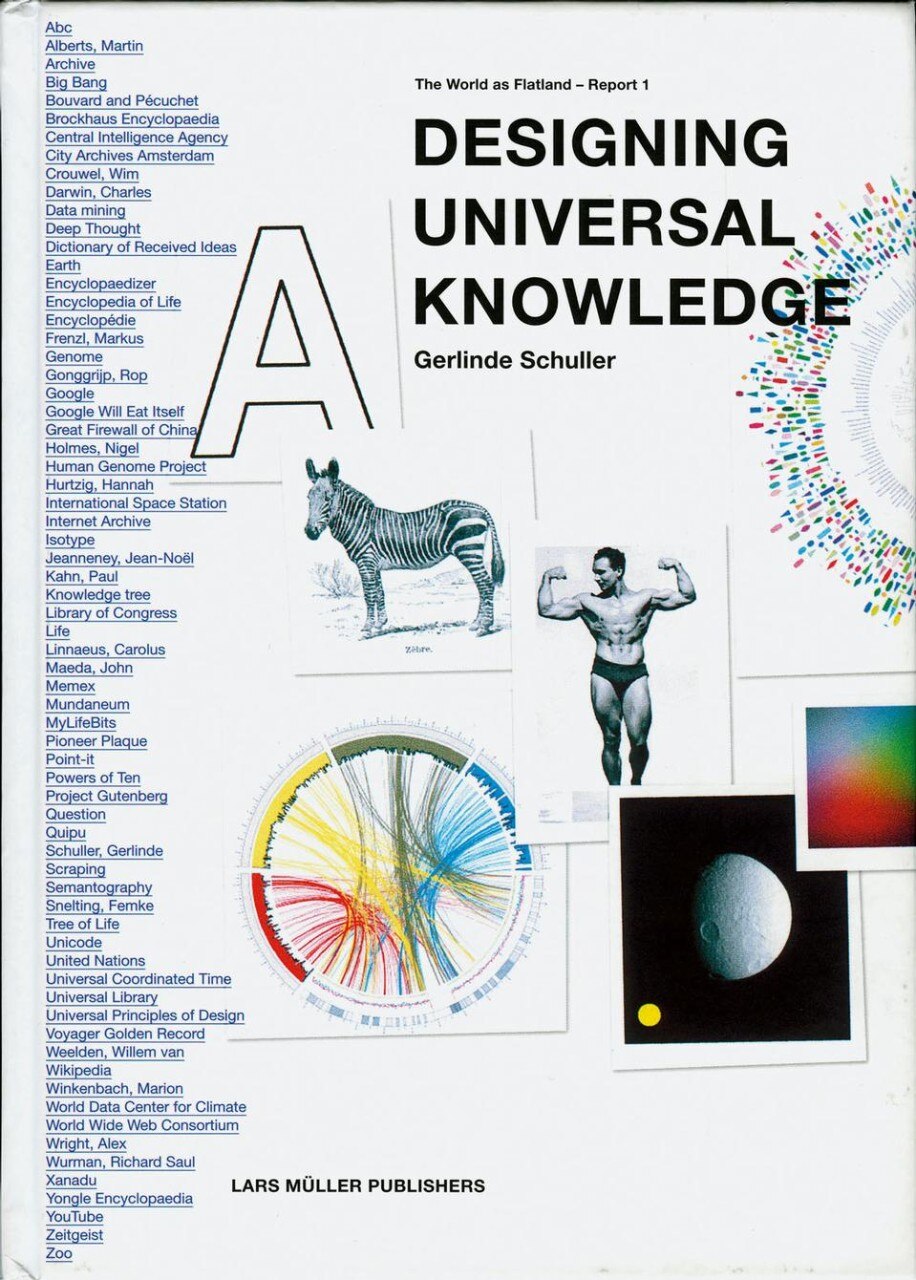

Designing Universal Knowledge

Gerlinde Schuller, Lars Müller Publishers, Baden 2009 (pp. 304, s.i.p.)

Alphabet, complexity, Encyclopaedia Britannica, genome, Google, Internet, knowledge management, non-knowledge, seed bank, simplicity, Trojan horse, World Wide Web, YouTube... these are just some of the 177 entries published by Gerlinde Schuller in her, selfconfessedly, ambitiously titled and intriguing book Designing Universal Knowledge. Who is collecting the world’s information? How are the archives of knowledge structured? Who determines access to the knowledge? What does the power of knowledge bring? These are the questions that prompted the research presented by Gerlinde Schuller in an “account” that investigates their meaning. Designing Universal Knowledge forms part of the series “The World as Flatland – Reports”, the first of three books on the design of complex information; the subsequent publications are Designing Breaking News and Designing World Projections. As the author explains, “The World as Flatland” is a metaphor for transferring complex information to the simplest “two-dimensional visualisation”. The Internet is comparable to other complex autopoietic models, systems that define themselves and tend to sustain themselves, like markets and, indeed, living beings. Gerlinde Schuller wants to simplify; she wants to bring order into the new world of Web 2.0, in which user participation in the creation of contents and in the various forms of communication, from videos to photographs, blogs and even software programmes, is ever more interactive, contagious, fast and, inevitably, chaotic.

Designing knowledge requires the ability to manage information, govern it and have rapid access to it when needed. The author resorts to a sort of dictionary in order to create order, provide certainties and help improve our knowledge in a modern environment such as that of the entropic and anarchic Web. This format displays the “knowledge” in a sure succession that is easily traced, and also borrows tools that are normally used on the Web such as hypertext and, despite the drawbacks of printed paper, hypermedia. Dictionaries are generally associated with the ability to classify words, a typically western cultural tradition. This tendency is inevitably also present in the most ignorant, discontinuous and disorderly among us, as “taxonomy” is not just linked to positivism, but it is also at the origin of scientific thought. The alphabetically orderd entries include interviews and essays by various authors As well as illustrating the meanings of the words shown, they also contain the personal biographies and, for those still living, their answers to four questions, usually the same: what is your favourite search engine? Do you go to libraries? Do you use encyclopaedias? Where do you get your information?

Basically, Gerlinde Schuller’s ambitious aim is to create a complete and updated collection of human knowledge, overcoming the inevitable shortcoming of entry selection by using hypertext, i.e. links to other entries in the book, which would be “active” were it a document on the Web. Certainly, those who are familiar with the speed and amount of information that Web 2.0 technology can circulate and those aware of its quality can only express broad consensus for Gerlinde Schuller’s work and great appreciation for the network of links studied for the various entries. It is of little importance whether or not the design of knowledge, which inevitably involves the manipulation of information, atones for the fact that it publishes, for instance, an entry on Aristotle – the precursor of the independence between science and philosophy – at the expense of the more mystical and complex Plato. Has Gerlinde Schuller’s project manipulated information? Has it violated the “virginity” of a free territory with no rules and where true and false, right and wrong, gourmet dishes and rubbish coexist without difficulty? It was time someone started addressing the problem. Gerlinde Schuller’s contribution introduces quality into the great mass of information, in a sphere in which the hub of online knowledge, the renowned Wikipedia, is developed partly with contributions from all its users, without exception.