Gunnar Asplund , Peter Blundell Jones, Phaidon, London 2007 (pp. 240, € 75,00)

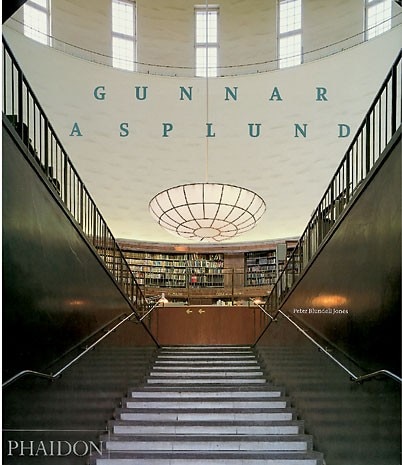

The reception given to Swedish architect Erik Gunnar Asplund (1885- 1940) has never quite matched his “success”, being instead more like a flow of alternating current. At regular intervals, books are published about him that are not, in all honesty, related to recent discoveries (the maximum intensity having been reached about 20 years ago, around the centenary of his birth) and are rarely linked to celebratory exhibitions. But this is precisely the point. An Asplund who was not a member of CIAM circles (unlike his perhaps equally littleknown colleague and rival Uno Ahréns) and who only built in Sweden could hardly don the prefabricated uniform of a stereotyped International Style. Works such as the Stockholm library with its imposing drum and the Delphic Gnÿthi seauton at the entrance left him branded with inescapable classicism, only possibly shaken by “dilemma”.

A label was always ready for any metamorphosis in his poetic, but can you really classify works such as the chapel in the woods of 1920, which is literally the squaring (on the outside) of the circle (on the inside)? Despite the erudite Swede’s passion for southern Europe, the Italian public knows little about Asplund. Nor did Cassina’s re-edition of chairs and armchairs (1983-1985) help to bridge the gap between us and a man who may occasionally have produced the most traditional Scandinavian furniture but sketched Mies’s tubular metal armchair on his notepad.

Faced with this fine book by the wellknown Blundell Jones we may well ask, “Is this another book on Asplund?” or, “Do we need a book on Asplund?” After overcoming the perplexity posed by the lack of a foreword (accompanied by an over-romanticised epilogue), this monograph reveals some clearly unquestionable qualities. First and foremost the historical contextualisation of Asplund’s life and training brings to life a sort of osmosis, not only between the modern movement and the Swedish Grace that arrived in Stockholm from Germany. We can say that one of the author’s basic aims is to try and reconcile apparently conflicting factors. He does not disregard the attributes previously adopted – modernity, romanticism, vernacular style – but brings them together in the originality of an architect who, on principle, never repeated even a single detail from a previous building. By translating some of Asplund’s articles published in specialist journals during the 1910s, Blundell Jones overcomes another obstacle, i.e. the Swedish language that only passed outside the nation’s borders in the manifesto Acceptera!, which loudly declared acceptance of modernity and called for standardisation of the industrial process.

The structure of this book with fluid boundaries acquires added effectiveness by focusing mainly on his constructed designs. Excellent photographs strive to show the buildings in a different light and archive drawings are used to great effect, the originals of which can no longer be consulted. The chapter on how the architect has been received by later generations does not, however, go into great depth. Could history have endorsed Asplund’s semi isolation, apart from the known legacy that poured into the work of Alvar Aalto? Readers are left with the impression of a discreet and rigorous figure who sometimes sings from a different hymn sheet and is on the verge of being démodé and evasive, as if no mediation has yet managed to bring him closer to us. In actual fact, this book clearly marks the boundary line as to what can be achieved by a publication on Asplund. The final warning is by no means banal: “Photographs and drawings, though they prepare one for a visit, are no substitute for direct experience.” (p. 229) We are coming closer to resolving the mystery surrounding Asplund, who, although elusive in words, used his architecture to convey a feeling of immediacy and protection for those who let themselves go on the inside, more than a sensation of being unrivalled when seen from the outside.

Donatella Cacciola Art historian, Bonn