Albe Steiner , Anna Steiner, Corraini, Mantova 2006 (pp. 168, euro 20,00)

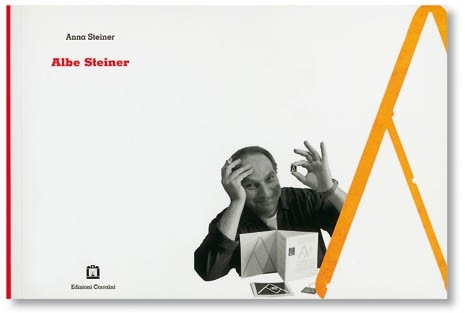

A bright smiling face and a left hand holding a stylised pair of compasses between thumb and forefinger. This fine cover photograph condenses more than one of Albe Steiner’s distinctive qualities. Optimism and faith in the potential of work; teaching and the concept that design is a form of culture to be handed down and cultivated (via the school and competitions, the Compasso d’Oro being one of the first); the love and fascination for his own tools – or rather, the entire world of objects. The special pair of compasses created by Göringer in 1893 to reproduce the golden proportions was, in this case, Steiner’s own. It ended up being photographed and reproduced in one of his own graphic productions, as did many other work tools: lead type, film clips and everyday objects. Quite frequently this also happened to hands (those of Max Huber appear in a poster for the studio that Steiner shared with his wife Lica). Creating the logo for a prize such as the Compasso d’Oro, which was to assume historic importance, was one of many contributions he made to the creation of a design culture. Steiner always insisted on research being seen as culture; teaching considered as a fundamental value and a core function of society certainly transpired from his direct involvement in the school. It was also clear in the way Steiner took his anti-decoration and functionalist approach to puritan extremes on the covers of Zanichelli textbooks, with just one clear element exemplifying each subject: a molecular model for the Chemistry manual, three polygons for geometry books. It was like saying that education is too important to waste time with frills. The importance of transmitting knowledge is, however, best summed up by the scene described by Giorgio Bocca in Una repubblica partigiana: Steiner carefully teaching graphic art to his partisan comrades. Even in the thick of battle, design is not a pastime to put off until less troubled times. This is also shown by headed notepaper reproduced in this book: “CLN. Corpo Volontari della Libertà. Divisione Val d’Ossola” (CLN. Voluntary Corps of Liberty. Val d’Ossola Division). It is unlikely that the French maquis or many other divisions of the Italian Resistance printed such elegant corporate identity accessories in secrecy – a project to which Steiner applied the same unhurried precision as he did years later in his works for La Rinascente and Pirelli. Fascism filled Albe Steiner’s life with bereavements: his uncle Giacomo Matteotti stabbed by Mussolini’s assassins, his brother who was deported and died in the Ebensee camp a few days before it was liberated, and members of his wife Lica’s family. If Steiner never ceased to focus on graphic design, not even at the height of the partisan war and his tragic experiences, it was also in the name of the concept that form and ethics were inseparable. In the memory published at the time of his death in 1974, Italo Calvino called it a fundamental aesthetic notion of the century: “The form of the things that surround us… of everything we need to communicate… expresses something, a mentality and an intention, i.e. the sense we want to give society.” In Steiner’s case, this link became more manifestly concrete after the war: his political commitment to the PCI, his graphic art for propaganda purposes and his work as a theoretician. In Mestiere del grafico he explored the ethical implications of a profession that had only recently been given a name. He asked graphic artists to work “for fruition and not speculation” and described the use of the results of production as “one of the rights of industrial civilisation”. Design and communication are a continuation of production and consubstantial to it; it therefore answers to the same imperatives of honesty, with a slightly monolithic concept of product “utility” by which graphic artists must refuse to push products that are not beneficial to consumers, or be an accomplice to fraud. Today, although the notion of a commodity’s usefulness requires perhaps more faceted approaches, the clear ethics still apply, unaltered. However, it is not always possible to teach this to adult designers who have not grown up with it, as Steiner did, and who sometimes hide the daily compromises reached with clients behind militancy displayed in terms of chief systems. Steiner was happy to frequent the chief systems: one of his posters guaranteed that “Lenin’s ideals live on” in the PCI (attaching a picture of Lenin saluting the people). The same utopian force was to be found on the covers of Rinascita and Il Contemporaneo, where Steiner continued the meditation on politics and culture commenced at the Politecnico with Vittorini. But the core of his ethical vision did not lie in utopia or simply in clear-cut personal morality. Every discourse on Albe Steiner’s moral dimension takes us back to things: the tools and objects that captured the attention of a designer who was convinced of his work’s significance; his insistence on the useful product; his loyalty to that product, invested with major expectations and worthy of loyal and minute attention. As art director for Pierrel, Steiner intervened on product design by increasing the thickness of certain tablets so that the maker’s logo could be impressed more deeply – also making it easier to break them into four. This is the encounter between form and morality evoked by Calvino. Principles that, at the very least, mean you read all the books for which you design a cover and, more generally, you immerse yourself in the world of things in which your design work develops. Concrete fact comes before the conceptual dimension because this will result in consistent design solutions. Simplicity is “resolved complexity”, as we are reminded in the first pages of the book: avoiding the obvious is entrusted to method and not theoretical lucubration or, worse still, extravagant creativity. This edition is true to this simplicity and to Steiner’s “object ethic”, with a good selection of materials from the Steiner archives, a wealth of preparatory sketches highlighting the design logic behind the works and the approach taken by Anna Steiner – a lecturer at Milan Polytechnic and daughter of Albe and Lica Steiner – in her notes: explanatory and not invasive, with a small space for personal memories and the recollection of the spirit that guided the work, an aspect accentuated in additional comments made by Lica. The reasonable price and small size of this paperback are qualities in keeping with the general approach to the work, although a larger format would naturally have done greater justice to some of the illustrations, which are squeezed into a few square centimetres.

Giuliano Tedesco Journalist